Planning is the Bottleneck to New Housing

Reforming states’ sclerotic land use planning systems is the key to building more housing. Both state and federal governments must do their part.

This essay appeared in edition three of Inflection Points.

You can listen to Brendan Coates discuss his essay and the Grattan Institute’s newest housing report on the latest episode of the Inflection Points Podcast, wherever you get your podcasts.

By Brendan Coates

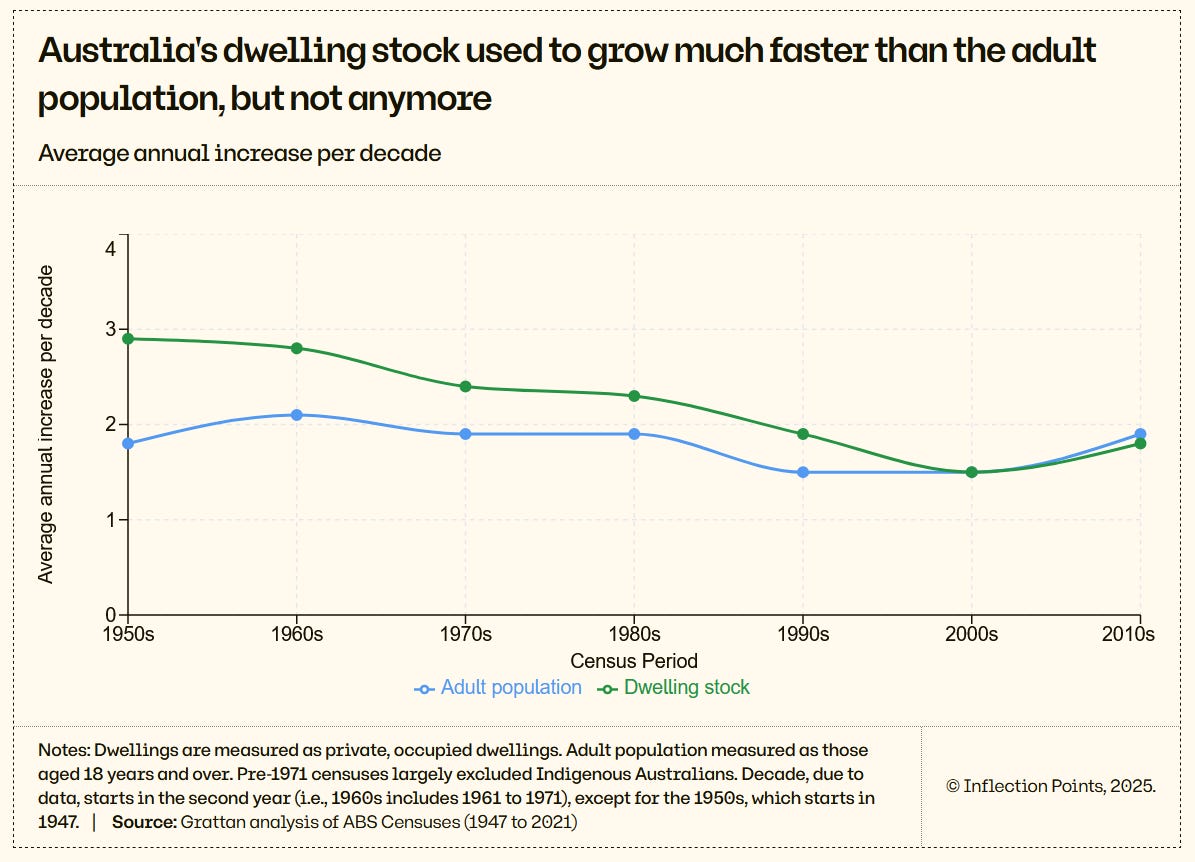

For the first time in decades, Australia’s housing stock is growing more slowly than its population. In the latter half of the 20th century, we consistently built enough to absorb population booms. Since 2000, we haven’t.

The problem runs deeper than simple population math. Falling household sizes, rising wealth, and work-from-home patterns mean we need to build more homes than population growth alone suggests. But because we’ve failed to build, house prices have exploded—from four times median income in the early 2000s to more than eight times today. In Sydney, the median home costs more than ten times the median income.

The shortfall is worst where it matters most

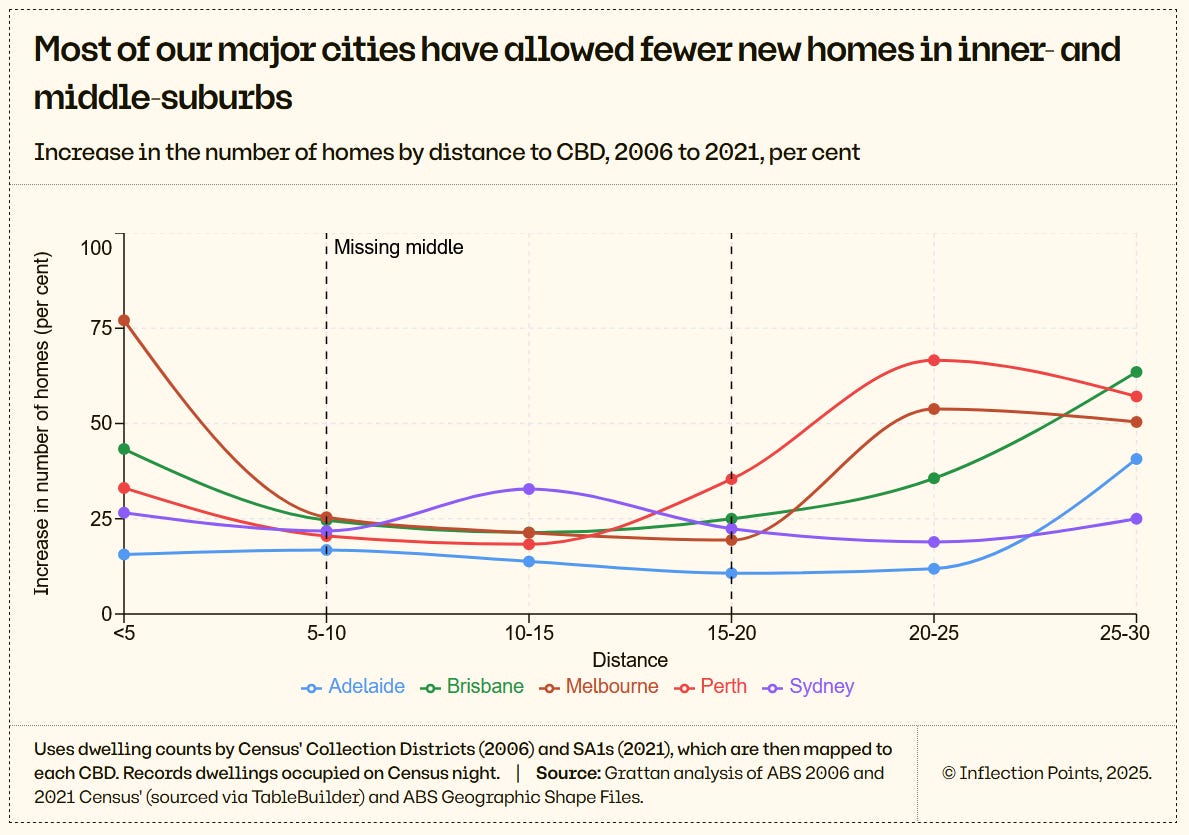

Australia has a particular problem: we’re not building where people want to live. Between 2006 and 2021, most major cities added the fewest new homes in the desirable inner- and middle-ring suburbs: precisely where housing is most expensive and demand is highest.

Many people would prefer a townhouse, semi-detached dwelling, or apartment in an inner or middle suburb, rather than a house on the city fringe, if more of those housing options were available in our biggest cities. But instead of enabling supply to meet demand in established areas, we’ve pushed the bulk of our development to the urban fringe.

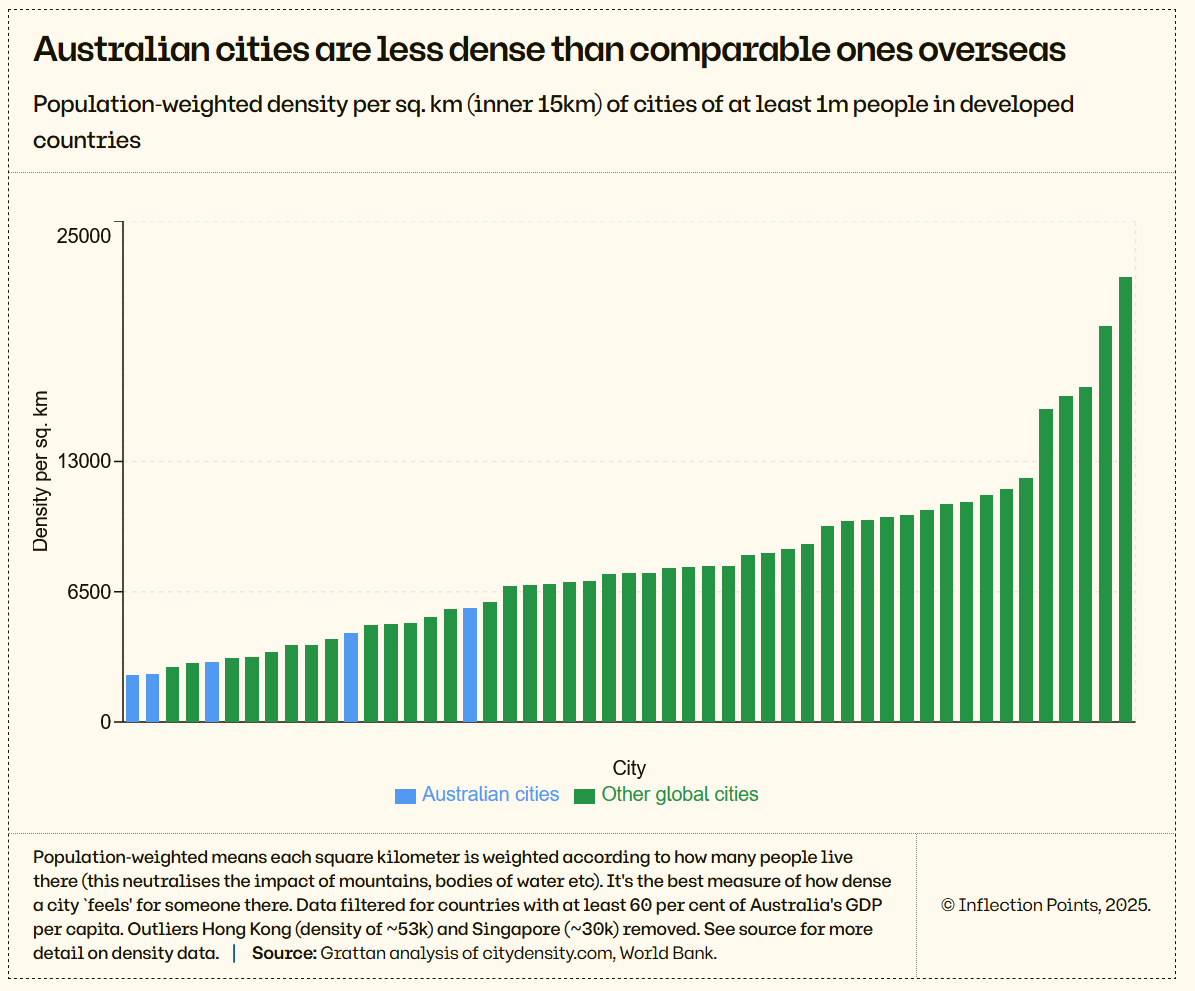

The result is that Australian cities are far less dense than comparable wealthy cities like Toronto, Copenhagen, or Vienna—cities that match or exceed ours on quality-of-life measures, yet house far more people per square kilometre. If inner Sydney were as dense as Toronto, it would have 250,000 additional well-located homes. If inner Melbourne matched Los Angeles, it would have 431,000 more. It’s no coincidence our nation’s cities have some of the most expensive housing in the world.

We are undermining our own prosperity

Australian cities are our economic engines. Cities generate productivity gains through agglomeration—clustering workers and firms creates economies of scale that boost wages. International surveys suggest every 10 per cent increase in employment density raises wages by up to 0.4 per cent. One Australian study found that doubling local density increases wages by 1.6 to 2.7 per cent.

But scarce and expensive housing is pushing people away from these opportunities, particularly the young, and particularly in Sydney.

The New South Wales Productivity Commission recently warned that Sydney risks becoming a city without grandchildren. Sure enough, from 2001 to 2024, 16 inner-Sydney areas saw their under-30 populations decline even as Sydney grew by 1.5 million people overall. Between 2016 and 2021, Sydney lost twice as many 30–40 year olds as it gained.

Those pushed to the outer suburbs face longer commutes and access to fewer jobs, making it harder for both parents to work, with women generally being the ones who end up working less. Rising housing costs are turning our most productive cities from ladders of opportunity into barriers to entry.

But there is hope. The political clout of renters has grown and the YIMBY movement has gained momentum. And for the first time in decades, the Federal Government is focused on housing.

This article lays out exactly what state and federal governments should do: first, by laying out the rationale for better land use regulation; then, by laying out the reforms that states—as the custodians of land use planning systems—should implement; and then, finally, by demonstrating how the Federal Government can and should play a coordinating role in bringing these reforms together.

Reforming state and territory planning systems will be an endeavour of the same scale as the great microeconomic reforms of the past—such as dismantling trade protectionism or establishing national competition policy. And like those great productivity-enhancing reforms that helped usher in decades of strong growth in Australians’ incomes, the returns to getting more housing built could be just as big.

Part I: Planning is the biggest (if not the only) problem

When the demand for housing in a location increases, so does the price of land. Land—and location—is in fixed supply.

But the amount of housing that we can supply at a given location is not fixed, because building upward is possible. Where planning controls permit extra housing to be built, the higher value of residential land prompts developers to build more dwellings on each unit of land, such as townhouses and apartment buildings. Townhouses and apartments use much less land per dwelling than freestanding homes, helping to keep housing affordable as demand for housing, and land values, rise at a location.1

But when restrictive planning controls prevent developers from building apartments and townhouses, the cost of housing will continue to increase with rising land values in high-demand areas. In recent decades, the price of land has risen faster than the price of buildings. In 2024, land accounted for more than 70 per cent of the value of residential property, up from 50 per cent in 1990.

Developers have not been able to build the density that would correspond to these rising land prices because our land use policies have forbidden them from doing so. And so housing has become much more expensive.

These restrictions on the construction of new housing are at the core of Australia’s housing woes. Too often, our planning systems prohibit more homes where people want to live and work, making housing scarce and unaffordable.

Of course, planning isn’t the only problem holding back more housing.2 But it’s the biggest. And the good news is it’s also the easiest to fix: it can largely be done without governments passing any new legislation, or spending more public money.

State and territory land-use planning systems have long managed the impacts of particular land uses and development on others.

Planners aim to manage the spillover effects, or ‘externalities’, arising from land uses—such as noise, pollution or buildings overshadowing—on the neighbours. Planning systems separate land uses that are clearly incompatible—such as putting a chemical refinery or an abattoir next to a school or housing.

And planners play a vital role in enhancing the public realm by coordinating the provision of infrastructure and green space.3

But existing planning controls restrict new housing in ways that are hard to justify against these core objectives of planning. There are three problems.

The first, and by far the biggest, is that state and territory planning systems say ‘no’ to new housing by default, and ‘yes’ only by exception. Built form controls make it illegal to build more housing on a lot of scarce and valuable land across our capital cities.

Second, approval processes for new housing, where it is allowed, are slow, costly, and uncertain.

And third, the governance of planning systems is biased against change, since councils prioritise the interests of existing residents, and there are no checks on bad rules being imposed that hurt those who don’t already live in those neighbourhoods.

Let’s take these problems in turn.

Problem 1: Land use planning controls say ‘no’ by default, and ‘yes’ by exception

State governments are responsible for land-use planning systems: they set the overall framework via legislation, they lay out the tools planners can use, and they allow for plans—maps and rules—that apply the tools to dictate what land can be used for. And in most states, these powers are delegated to local councils—including processing most development applications.4

Planning controls include zones that can be used to separate different land uses and regulate their intensity, as well as other prescriptive rules, such as:

minimum lot sizes,

minimum lot width,

setbacks,

site coverage maximums,

floor space ratios, and

other protections such as heritage and neighbourhood character, which further limit what can be developed.

Dense housing is banned across most of our capital cities

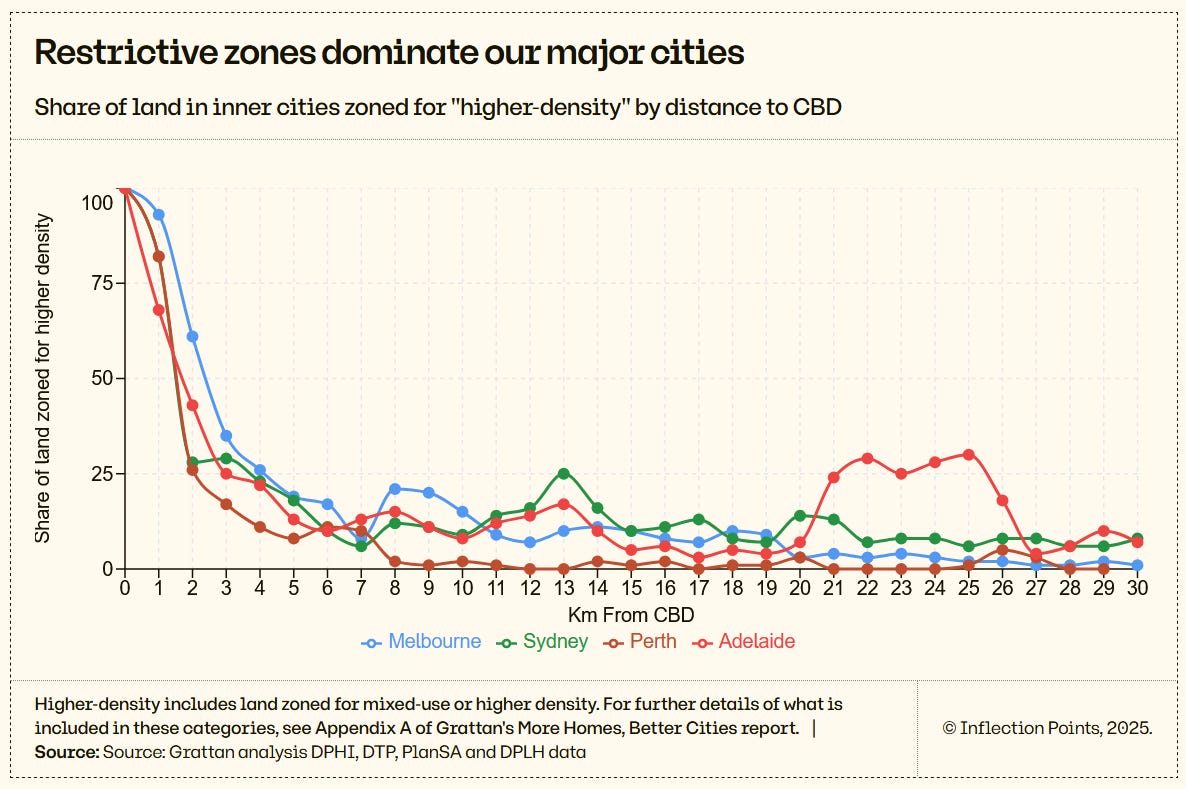

About 80 per cent of residential land within 30km of the centre of Sydney, and 87 per cent in Melbourne, is restricted to housing of three storeys or fewer.5

But this isn’t just a problem in our two biggest cities: three quarters or more of residential land in Brisbane, Perth, and Adelaide is zoned for two storeys or fewer.6

And planning controls are often even stricter in regional Australia.

Other prescriptive rules—such as minimum lot sizes, setbacks, and street frontages, and other protections such as heritage—further limit what can be developed. In fact, these other controls are often just as big a barrier to greater density as height limits.

Site coverage maximums make housing difficult to build

For example, while parts of Ku-ring-gai Council in Sydney permit multi-dwelling housing, they set a maximum site coverage of 40 per cent and a minimum setback from the front boundary of 10 metres. This means that for a 10 metre by 40 metre parcel of land, the 100 square metres closest to the street is off limits, and only 160 square metres of the remainder is available to build on. After taking into account other controls such as minimum side and rear setbacks, and minimum private open space rules, it quickly becomes difficult to build multi-dwelling housing on a site that is—on paper—zoned to allow it.

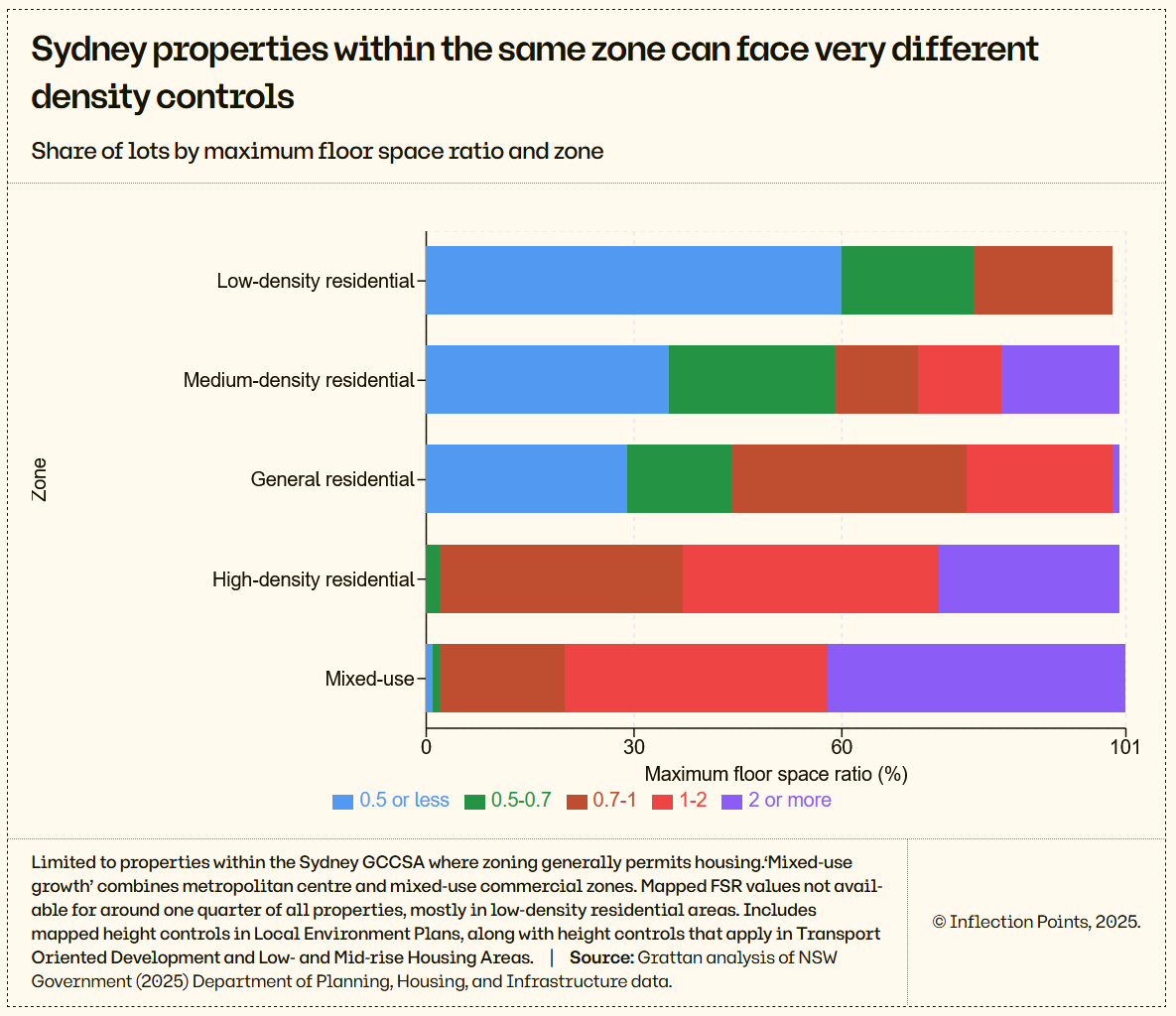

New South Wales’s floor space ratio controls undercut reforms intended to enable density

Maximum floor space ratio (FSR) controls control how much floorspace can be constructed on a given site. For instance, a 1000 square metre lot with an FSR of 2 would enable 2000 square metres of floorspace to be constructed. An FSR of 0.8 would enable just 800 square metres of floorspace to be constructed, regardless of height limit controls.

And across NSW, highly stringent maximum floor space ratios are widely used in ways that undercut residential zones notionally intended to permit higher-density.

For example, the ‘high-density residential’ zone in NSW is intended to ‘provide for the housing needs of the community within a high-density residential environment’. But nearly three-quarters of land zoned as such in Sydney is subject to a maximum FSR of less than two, even after recent planning reforms.

High minimum lot sizes make even subdivisions infeasible

Even recent reforms to allow the subdivision of existing blocks in NSW for dual occupancies are hampered by restrictive minimum lot sizes. These restrictions range from 450 square metres for sites in many councils to 1,000 square metres in Ku-ring-gai Council, to 6,000 square metres in Albury.

The combined impact of these controls means development theoretically allowed is often practically infeasible, especially in the case of urban infill where the existing home must be bought and then demolished.

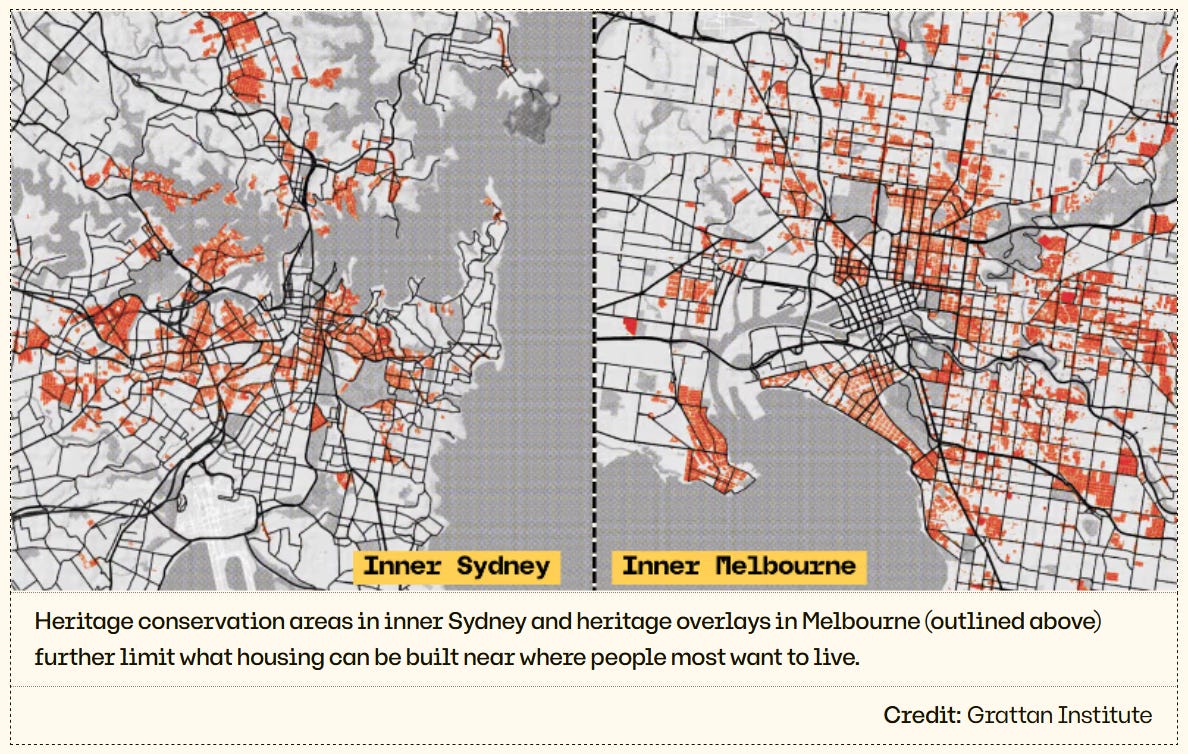

Broad heritage controls lock up much of our inner-cities

These rules impacts are often exacerbated by heritage protections, which further limit where housing can be built. While prominent heritage buildings are specifically listed on federal and state heritage registers, the bulk of heritage protections are applied by local councils to properties within broad areas via local planning schemes.

Inner-city councils in Sydney and Melbourne have used these powers liberally. In Sydney, 21 per cent of residential land within 10km of the CBD is covered by heritage protections. In Melbourne, 29 per cent of residential land within 10km of the CBD is covered by a heritage overlay.

And ‘character zoning’, unique to Brisbane, requires the retention of pre-1947 homes, and requires that additional buildings reflect the existing character of the area. Character restrictions apply to nearly 13 per cent of all of Brisbane’s residential-zoned land, and most residential lots in the highly desirable neighbourhoods within 5km of the CBD.7

Protecting certain sites that enrich our shared understanding of history is important. But these controls are often imposed extensively with little acknowledgment of the consequences of stymieing the supply of housing in areas where people most want to live.

Heritage protection ultimately means fewer homes. In Melbourne, sites with heritage overlays were about 50 per cent less likely to have had significant infill development than those without from 2017 to 2022. In this same timeframe, mixed-use developments in heritage overlay areas had on average 28 per cent fewer storeys than those elsewhere.

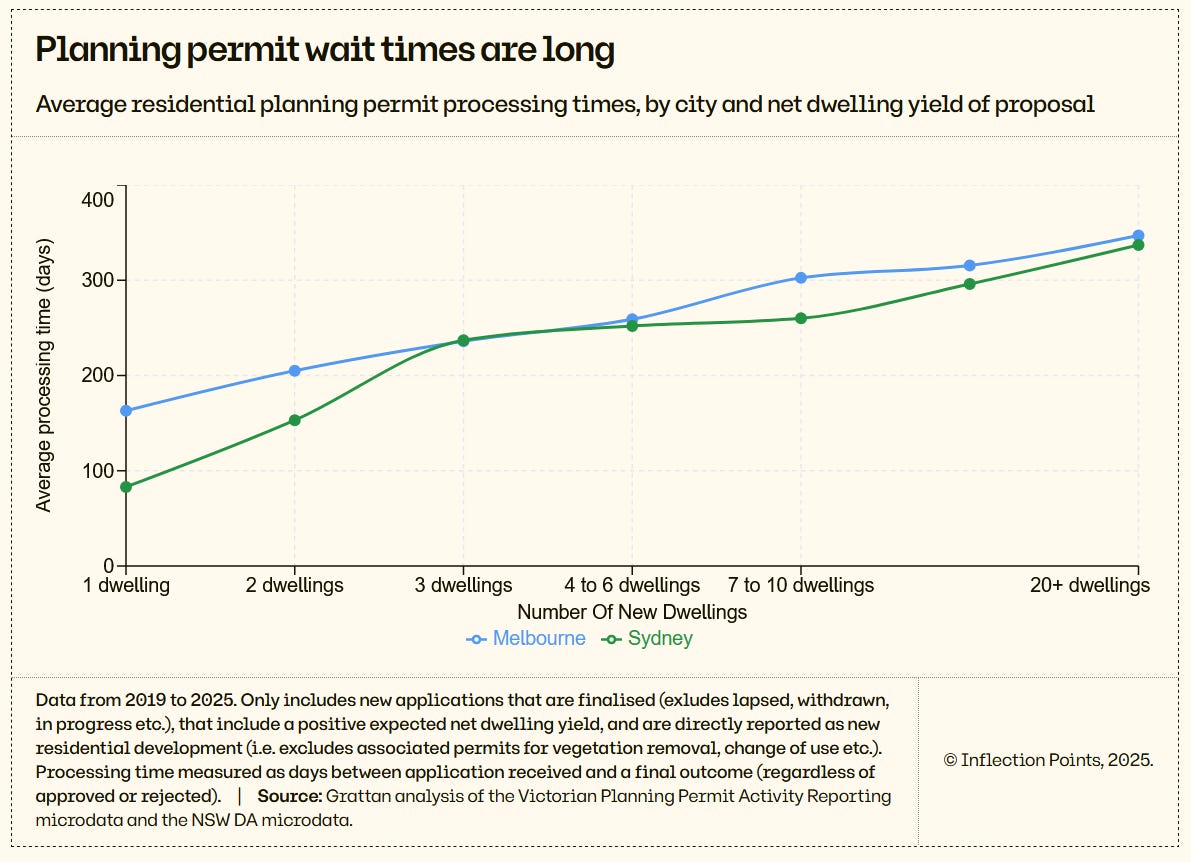

Problem 2: Planning approval processes are complicated, long, and uncertain

Most new housing requires a planning approval, typically from a local council. But approval processes for new housing—where it is even allowed in the first place—are slow, costly, and uncertain.

Over time, the work required to lodge a development application and comply with planning rules has increased significantly.

For example, a development application to build an apartment building in Sydney in the late-1960s was just 12 pages long. Today, a development application for planning approval for a similar apartment building runs to hundreds of pages and requires extensive environmental, traffic, and often heritage assessments.

These are typically prepared by consultants, adding thousands of dollars to the cost of building new homes.

Broadly, councils accept or reject proposals based not only on what the specific rules of their local plan say, but also the strategic objectives for a given parcel of land. And councils tend to have a wide berth to lay down restrictive objectives for areas.

Here are just two examples.

Boroondara Council in inner-eastern Melbourne has added an objective for some of its jurisdiction to maintain the ‘spacious, suburban character of the area’, as well as the area’s ‘leafy’ feel.

Similarly, Woollahra Council in inner-eastern Sydney says that development in its most common zone (R2) should be ‘...compatible with the character and amenity of the surrounding neighbourhood’ and ‘...of a height and scale that achieves the desired future character of the neighbourhood’.

In the best case, it’s difficult to understand how to comply with these objectives; in the worst case, they are actively hostile to new development.

Wait times for planning decisions are also often long: they are nearly a year on average for developments of 20 or more homes in NSW and Victoria.

Most states and territories have created streamlined pathways for development applications, but too few new housing developments typically qualify.8

And in some states, especially Victoria and Tasmania, third parties—neighbouring landowners, tenants, or members of the broader community who may be adversely affected by a proposed development—can appeal against planning decisions.9 This gives yet another group the right to either veto, or delay, housing.

Delays add to project financing costs, and increase the markup required to make new housing commercially feasible for developers.

These delays can cause developers to abandon or postpone projects. And because construction is highly sequential, delays and disruptions can create ‘cascading failures’ which push up costs by requiring repeat consultants’ reports, or delaying timed access to scarce labour and materials.

The additional holding costs—mostly financing and taxes - from waits can be material. For instance, an extra six months of permit processing time after buying a block of land in Sydney to build townhouses can add about $18,700 in developer costs per home.10

And many development applications are approved subject to conditions, including variations to the design of the building, or approvals from energy or water infrastructure providers. These conditional approvals stretch out timelines even further.

One NSW developer reported that they went through a development approval process with 230 conditions that needed to be addressed before they could receive a construction certificate.

These can make otherwise profitable developments commercially infeasible, especially when these changes are requested late in the planning and design process.

Problem 3: The governance of land-use planning is biased against change

The governance of land-use planning—who decides what gets built and where—is biased towards local residents who oppose change. People who might move to the area—were new housing to be built—don’t get a say.

Councils are mostly held accountable by those opposing change, meaning that they receive little pushback on rules that are overly restrictive.

When Ku-ring-gai Council in Sydney consulted residents on proposed upzoning reforms in 2024, just 4 per cent of respondents were renters and 12 per cent lived in apartments. This is a large shortfall when compared to the 2021 Census, which showed that 20 per cent of residents in the area were renters, and 27 per cent lived in apartments.

Similarly, an analysis by YIMBY Melbourne of community consultations found that older residents were over-represented in 14 of the 15 consultations examined, and homeowners were over-represented in all 15.

In many other areas of policy, those proposing to restrict peoples’ choices would be required to reckon with the impact. But new land-use planning rules are not subject to any robust regulatory impact assessment process.

Land-use planning rules benefit existing residents by, for example, preserving views or preventing increased congestion. But studies conclude that the costs of restricting building are much larger—for example, inadequate housing, higher housing costs, and lower incomes from foregone agglomeration scale economies.11

Legacy planning rules make housing scarcer, and more expensive, than it needs to be

By restricting the ability to build denser housing in desirable areas, planning rules drive a wedge between supply costs and market prices. The gap between what people would be willing to pay to put apartments on a block of land and the current price of that land per extra apartment is an effective measure of how much planning controls are restricting housing on a given site.

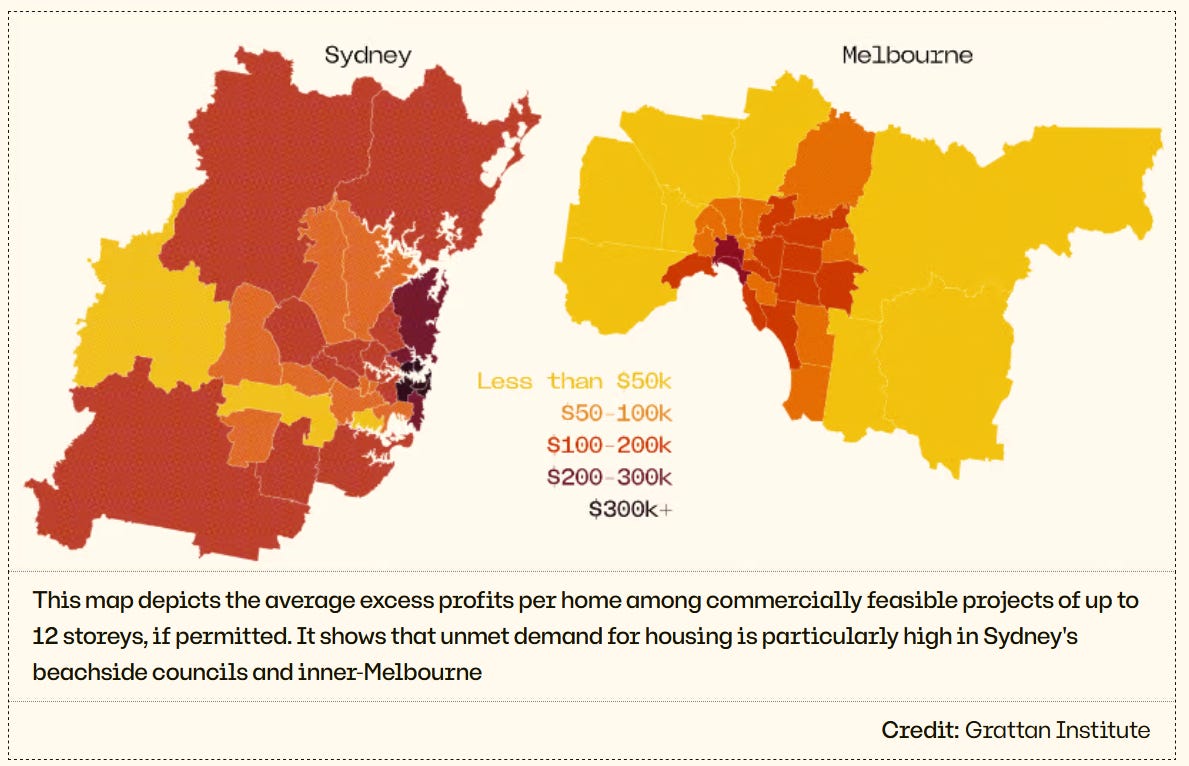

To estimate the impact of those controls, my colleagues and I at the Grattan Institute have estimated average excess profits from building new housing if it were allowed—i.e. profits above the 18 per cent margin usually required to finance development—by comparing the cost of building a series of urban infill housing project of up to 12 storeys in Sydney and Melbourne to the likely sale prices of the new homes across both cities.

Among commercially feasible projects—selecting the most profitable infill option for each site—we estimate an average excess profit of up to $490,000 in Woollahra Council in Sydney, and up to $270,000 in the City of Melbourne. That is, developers could currently sell these extra homes, if they were permitted on these sites, for substantially more than the cost of building them, even accounting for the costs of acquiring the land, all fees and charges, financing costs and a developer profit margin of 18 per cent. Average excess profits are highest in Sydney’s beach-side suburbs, and Melbourne’s inner east, reflecting greater unmet demand for floorspace in these areas.

Similarly, work by Reserve Bank researchers in 2018 estimated that planning restrictions added up to 40 per cent to the price of houses in Sydney ($489,000) and Melbourne ($324,000), and about 30 per cent in Brisbane ($159,000) and Perth ($206,000), up sharply from 15 years earlier.

Part II: What state governments need to do

For too long one of our most important regulatory systems -- that which regulates where people can live and in what types of housing, and where they can work—has been left to planners, councils, and state planning departments. This lack of oversight has led to the creation of a set of systems that say no by default, and yes only by exception. They force developers to build fewer homes than they would have otherwise, and force individuals and families to settle for housing options that often don’t best suit their needs.

But planning systems should be designed to maximise people’s choices about where they live, work, and do business. The higher the demand for a location, the more housing should be permitted at that location. Land use policy should be focused on enabling supply to meet demand, through coordinating and pricing infrastructure, and resolving public-realm conflicts—instead of defaulting to implementing restrictions.

By employing laser focus on maximising choice and delivery in line with demand, planning systems will be more effective and empowering for Australians. And planning controls that restrict where housing can be built—but which can’t be justified on the basis of these fundamentals—should be removed.

We need to allow a lot more housing than we ever expect to build

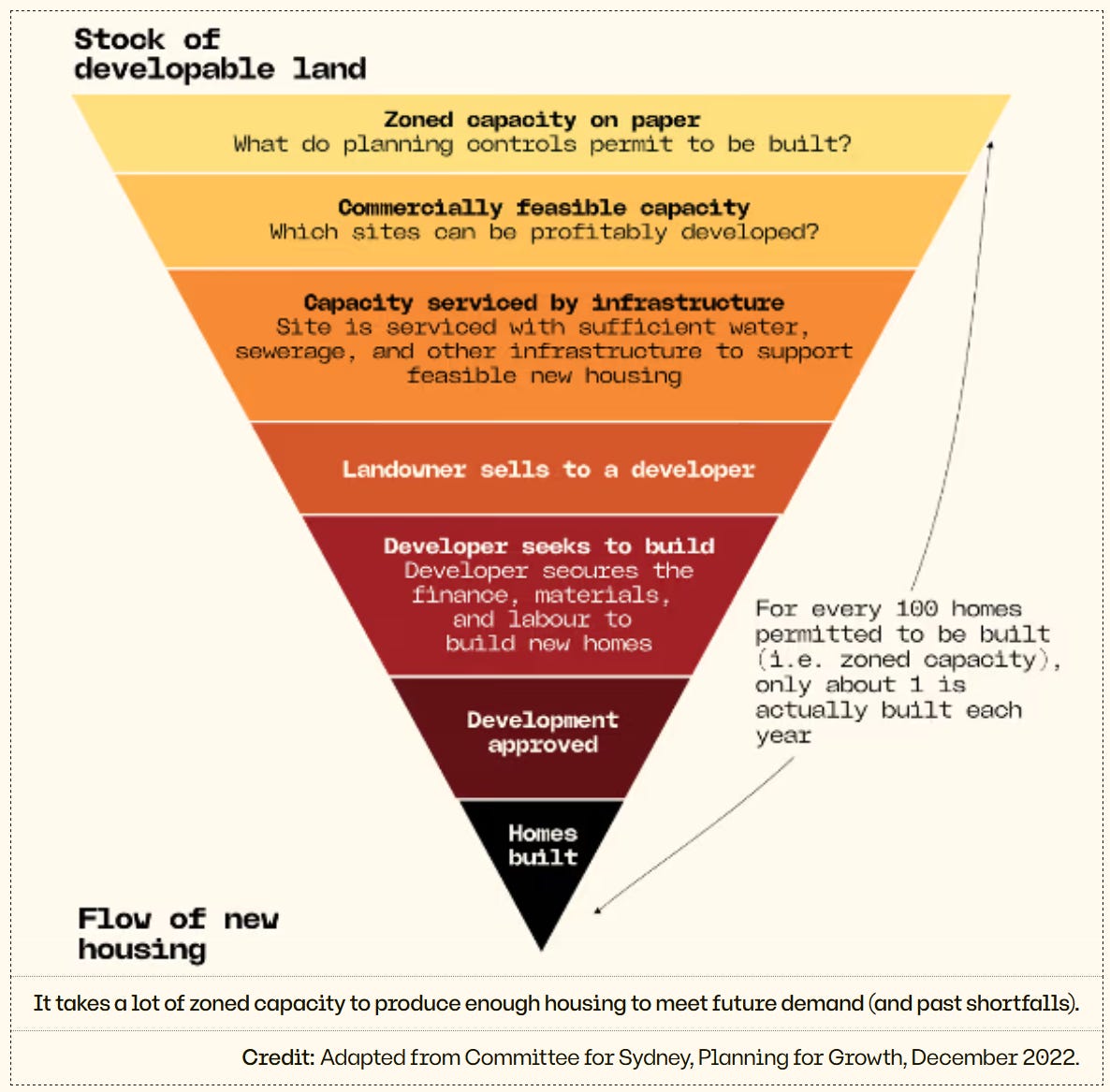

Local councils and government planning agencies will often argue that they have zoned sufficient land for further development.12

Yet much of this zoned capacity is merely theoretical. Much of this zoned capacity is commercially infeasible to develop once the cost of demolishing existing dwellings is taken into account, especially where the number of extra homes that can be built is low. The more homes that can be built on a given site, and therefore the higher the potential profit, the more likely the development will go ahead.13

And not all sites will be built on: many owners of sites that could profitably accommodate more housing will not want to sell. Or it may be impractical to service all commercially feasible sites with the necessary infrastructure.

So it shouldn’t be surprising that a recent survey of zoned capacity in California showed that on average, only about 1 per cent of all zoned capacity is built as new housing each year. And a recent New York study found that only about 9 per cent of any increase in permitted floorspace was developed into new housing over 10 years, with only profitable sites subsequently redeveloped.

Given all these frictions, we need to allow for a lot more housing than we ever expect to build over the next few decades.14

Three-storey homes should be legal across our capital cities

Australia’s state, territory, and local governments should relax planning controls to permit more housing—especially townhouses, units, and apartments—in our capital cities where demand for housing is highest.

State and territory governments should adopt a Low-Rise Housing Standard that permits townhouse and apartment developments of up to three storeys on all residential-zoned land in Australia’s capital cities. There should be no prescribed minimum lot sizes, and the permissible site coverage should be at least 65 per cent.

These developments should not require a planning permit, just like many knock-down rebuild homes in many states already.15 Developments would still need to secure a building permit and therefore meet all building standards.

This reform would permit substantially more homes in our cities while imposing only modest costs on neighbours via overshadowing or changes in the streetscape.

Townhouses take just under a year to build, on average, compared to just over two years for apartments. And three-storey townhouses are likely to be particularly profitable to build, since a garage at ground level is much cheaper to construct than sinking a basement carpark, and the extra height to three storeys will in many more cases justify the cost of demolishing the existing home.16

Subdividing large family homes for townhouses is an easy way to boost density and allow more housing on scarce inner-city land without the need for lot amalgamations. Around half of all residential-zoned blocks in Sydney and Melbourne are larger than 600 square metres, as are nearly two-thirds of those in Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide.

For example, allowing three-storey townhouses and units across all residential land in Sydney, as we recommend (and as is largely already permitted in Melbourne), would add capacity for more than 1 million new homes that could be profitably developed today.17

Apartments should be legal around transit hubs

Australia’s state and territory governments should also adopt a Mid-Rise Housing Standard, which permit developments of a minimum of at least six storeys in high-demand locations in capital cities, such as:

Within at least 2km of the edge of the CBD

Within at least 400m of key transit hubs, including train, tram, and high-frequency bus stops

Around other high-demand locations, such as other inner-city locations, and commercial hubs.

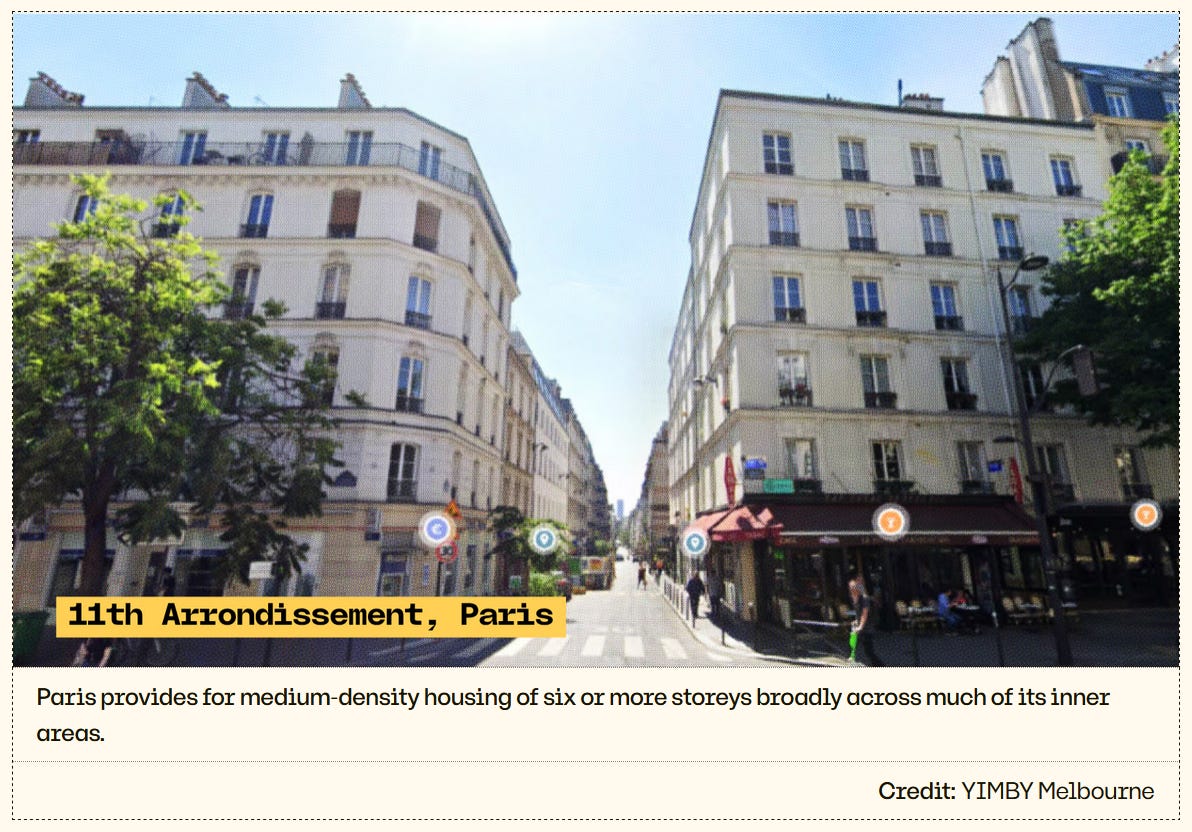

Many of the world’s most iconic and liveable cities—such as Paris, Vienna, and Copenhagen—provide for medium-density housing of six or more storeys broadly across much of their inner areas. This allows many more people to live where the city is at its best: near transit and cultural hubs, near their jobs, and near their friends, their families and their communities.

Allowing six or more storeys in high-demand locations also increases the prospect that the extra homes will be profitable to build after accounting for the costs of purchasing and then demolishing any existing buildings on a site.18

And state governments should also permit much higher densities than six storeys in capital city CBDs and other high-demand locations where those densities are commercially feasible to build.

While neighbours and urban planners often prefer low- and mid-rise apartments for urban infill, the commercial realities of building new homes often demand higher densities to make projects commercially feasible since the costs of acquiring a site can be spread across more homes.

An assessment of New Zealand’s National Policy Statement on Urban Development (NPS-UD), which required councils to allow for apartment buildings of at least six storeys along key transit corridors, found that the benefits of greater density exceeded the costs by a ratio of seven to one in Wellington and five to one in Auckland.

NSW and Victoria are already enacting ambitious reforms

But thankfully, the politics of planning are shifting. The state governments of NSW and Victoria have responded to the crisis with bold reforms to planning controls to allow more homes to be built in the established suburbs of Sydney and Melbourne. What’s more, these efforts appear popular.

Grattan Institute calculations show that the NSW government’s reforms could boost zoned capacity—the number of homes that are permissible to build—within Sydney by more than 900,000 dwellings, the equivalent of 40 per cent of the city’s existing housing stock.

Whereas similar reforms in Victoria allow for an extra 1.6 million homes in Melbourne. That’s the equivalent to 70 per cent of all homes in Melbourne today.

And the better news is that about one third of that capacity can be profitably built today, despite higher construction costs. This is particularly the case for townhouses in both cities, which remain nearly as cheap to build as new freestanding homes on the urban fringe, and taller apartments in the eastern and northern suburbs of Sydney.

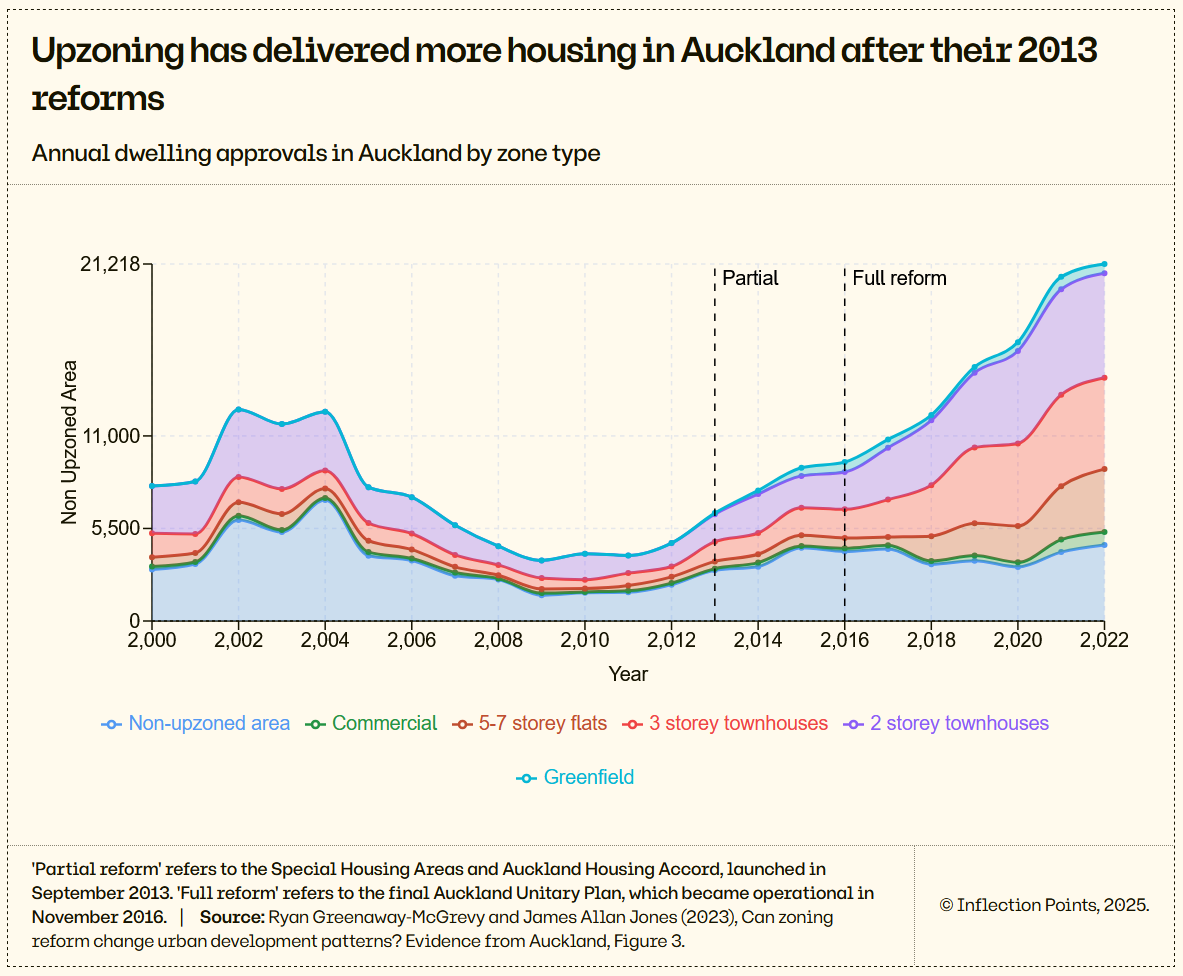

But both states’ reforms fall short of recent reforms in Auckland, which lifted zoned capacity by the equivalent of 100 per cent of all existing homes.

The NSW government, in particular, could unlock capacity for more than 1 million extra commercially feasible homes in Sydney if they followed Victoria and allowed three-storey townhouses on all residential-zoned land.

But all state governments still have more to do.

More homes would make housing cheaper, and our cities better

A planning system that allows more homes where demand is high will lead to more and cheaper homes, especially in the long term.

If our proposed reforms had the same impact on new housing construction nationwide as is expected with similar reforms in New Zealand, they would lift annual housing construction in Australia by an average of more than 67,000 homes each year, over the next decade.19

Such a boost to housing construction would result in house prices and rents being up to 7 per cent lower than otherwise after five years and 12 per cent lower after a decade. The typical renting household could be up to $1,800 a year better off, and more than $100,000 could be shaved off the cost of a median-priced home.

And the benefits of these reforms would continue to build in the long term. For instance, should the uplift in housing construction continue over two decades, these reforms could deliver an extra 1.3 million homes, reducing house prices and rents by more than 20 per cent.

These estimates are not merely theoretical. In 2016, about three-quarters of the residential land in Auckland, New Zealand, was up-zoned.20 Researchers have found it led to an increase in housing supply of at least 4 per cent in just six years. Most of this new stock was extra townhouses and small apartment buildings. That extra housing reduced rents for two- and three-bedroom dwellings by up to 28 per cent compared to where they would have been without the reform. And today, house prices in Auckland are 15 per cent lower in real terms (i.e. after inflation) than in 2016, compared to a 13 per cent rise for New Zealand as a whole.

Auckland’s experience reflects a large body of evidence which shows that when planning controls are relaxed, the result is more and cheaper housing. And removing minimum lot sizes in particular can boost density in less built up areas, which is likely to be especially important in our smaller capital cities.

In fact, relaxing planning controls means that housing supply can accelerate at the same time that house prices grow more slowly, or even fall. By substantially increasing the number of sites where new housing is allowed, planning reform can reduce the cost of land for development by reducing the scarcity premium built into land values today. Since developers would pay less for the land they need for each new home they build, they could sell homes for less and still make a commercial return.

And there are good reasons to be optimistic that we can build that many homes in the long term. For example, over the past 10 years, the number of people employed in construction in Australia grew by 30 per cent to reach 1.3 million—almost one-in-10 workers.

Newly-built townhouses and apartments, while often expensive, are much cheaper, on average, than the existing freestanding homes that they replace. And building more expensive homes can “soak up” demand for housing from wealthier residents who might otherwise bid up the price of less-expensive homes..

Boosting housing supply would especially help low-income earners. Irrespective of its cost, each additional dwelling adds to total supply, which ultimately improves affordability for all. This is because the people who move into the newly-built dwellings vacate their existing homes. These ‘moving chains’ quickly free up cheaper homes for lower-income households.

And newly built homes in established suburbs are also typically much higher quality than the homes they replace. For example, 90 per cent of established houses have an energy efficiency rating of less than 6 stars. The 2022 edition of the National Construction Code requires a 7 star minimum—requiring around 25 per cent less energy than the 6 star equivalent.

Allowing more housing would boost Australians’ incomes

Relaxing land-use planning controls—and thereby letting more people live and work where they want—could boost Australians’ incomes by up to $25 billion a year (in today’s dollars), or 1 per cent of GDP in the long term.

That boost would come from letting more people live in high-wage locations, and from larger agglomeration scale economies arising from greater density. And that estimate doesn’t capture the big benefits Australians would enjoy from accessing housing that better suits their needs.

Our cities would change only gradually

There is no reason we cannot have more homes where people want to live while also still protecting green spaces and key heritage sites. For instance, adding extra homes in the northern and eastern suburbs of Sydney, or the leafy eastern suburbs of Melbourne, would simply ensure that more residents could enjoy the abundant open spaces and other amenities in those suburbs.

Despite producing a substantial increase in housing construction in high-demand areas, the urban landscape would change only gradually.

If Melbourne were to absorb 20 per cent of the extra 1.3 million homes we anticipate nationwide over the next two decades on land within 15km of the CBD, population density in that area would still be lower than that of Los Angeles today.

Building more homes close to the centres of our major cities would add much less to congestion than if those new residents were pushed to the outer suburbs. For example, congestion costs per extra resident are up to seven times lower in areas closest to the city centre of Sydney.

Denser cities are also better for the climate—a sprawling, car-dependent city pumps more CO2 into the atmosphere.

And denser cities are better for the economy—allowing more employers to locate closer together increases knowledge spillovers and gives workers more options.

Increased density can also encourage everyday interactions, and foster greater understanding between individuals from different backgrounds.

Building more housing in established suburbs is also cheaper for taxpayers. Servicing a new home in an established suburb with infrastructure can be up to $75,000 cheaper than servicing the same home on the urban fringe.

In short, these planning reforms would leave Australians better off on practically every dimension that matters.

Part III: What the federal government should do

For the first time in decades, Australia has a federal government that appears serious about solving Australia’s housing supply problem, and the National Cabinet agreement to build 1.2 million homes over five years from 2024-25 was a major step forward.

That Plan included $3.5 billion in incentive payments to push the states to get more housing built. But those incentives need major improvements in order to effectively move the needle in favour of more housing supply.

Federal and state governments are falling well short of the Housing Accord targets

An ambitious target is important in focusing attention on the problem of our national housing shortfall and building momentum for change. And building 240,000 homes a year over five years would make housing in Australia significantly cheaper, especially if that pace of homebuilding was maintained over a decade or more.21

The highest-impact policies available right now should focus on tipping the scales for state governments to take the actions needed to get more housing built in the future.

The federal government’s trump card to date has been the $3 billion New Homes Bonus: an offer to pay the states $15,000 per home that gets built over five years to 2028-29, above that state’s share of a 1-million-home baseline.22

But the New Homes Bonus isn’t working. The post-COVID downturn in housing construction, caused by a sharp jump in both interest rates and the costs of construction materials and labour, mean the target is unlikely to be met. There were only 188,000 new housing approvals in the year to August 2025, and the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council expects net new housing supply to total just 938,000 homes over the five years to 2028-29.

That means the states collectively are likely to substantially undershoot the national baseline for qualifying for the New Homes Bonus, even if they undertake ambitious reforms now. Only Victoria is on track to exceed the baseline and receive any payments.

The New Homes Bonus is not working

This points to the limits of paying state governments for an outcome—the rate of new housing construction each year—which they do not fully control.

Relaxing land-use planning controls would lead to substantially more new housing being built each year on average. But housing construction would likely remain highly cyclical.

For example, changes in interest rates materially affect the flow of new housing, as do construction and labour costs, which are driven in part by global and national economic conditions.23

Over a decade or more, these cyclical factors would wash out. But an incentive scheme covering such a long period is inconsistent with the length of state or federal parliamentary terms.

The New Homes Bonus could be made somewhat more impactful by bringing it forward to be paid in instalments, subject to progress towards meeting a recalibrated baseline — rather than it being paid out as a lump sum at the end of the five-year period.

But the federal government should focus on rewarding state governments for specific reforms that evidence tells us should lift housing construction in the long term and which are entirely within their control.

The federal government should reward states that adopt specific reforms that lead to more housing

The federal government should reward state governments that enact specific, ambitious, and verifiable reforms that relax residential land-use planning controls to allow more housing to be built.

Specifically, the federal government should reward states that adopt the Low-Rise and Mid-Rise Housing Standards outlined earlier. These reforms would tackle the two big problems with land use planning and housing: that existing planning controls are too restrictive; and that development approval processes are costly, slow, and uncertain.

There’s plenty of precedent for the federal government helping to pay for specific, verifiable economic reforms. Under the National Competition Policy, the Commonwealth paid the states almost $6 billion over 10 years in exchange for much-needed regulatory and competition reform. The Productivity Commission later concluded that this reform boosted Australians’ incomes by 2.5 per cent.

An inherent principle of National Competition Policy is that it’s better to pay for specific changes to law or regulation that offer an economic payoff, rather than simply rewarding states that boost GDP per capita year-to-year.

These payments should be made to the states by extending the National Competition Policy to cover reforms to residential land-use planning rules.24 The National Competition Council should monitor whether states have enacted these reforms.

State governments could be offered a menu of options that reflect different levels of ambition towards meeting the new Standards, with lower payments offered for less ambitious reforms.

For example, states that adopt a variation of the Low-Rise Housing Standard that permitted only two-storey developments (rather than three) in all residential zones could be paid a lower amount than states that adopt that standard in full.25

Similarly, states could be offered the opportunity to adopt a less ambitious version of the Mid-Rise Housing Standard that requires only four storeys around transit hubs, rather than six storeys.

And state governments that have already made meaningful reforms to relax planning controls to allow more housing, such as the NSW and Victorian governments, should be rewarded with a top-up payment in recognition of those reforms, subject to agreeing to doing further work.

The federal government has already committed $900 million via a new National Productivity Fund to encourage state and territory governments to adopt “pro-growth” policies from a menu of options, including reforms to commercial planning and zoning.

Given that most states appear unlikely to qualify for the full $3 billion on offer via the New Homes Bonus within the five-year window of the Housing Accord, payments for planning reforms under the National Competition Policy could be funded by reallocating $1.5 billion from the New Homes Bonus to National Competition Policy.

The federal government could, in time, offer incentive payments to state governments that relax car-parking requirements, apartment design controls, and heritage policies in ways that makes more housing commercially feasible to build.

Australia needs better federal housing research

New Zealand’s Productivity Commission proved pivotal in driving their country’s national planning reforms to boost housing supply. But government action in Australia to boost housing supply is hampered by a lack of research and analytical capacity on the barriers to building more homes.

The Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), funded jointly by federal and state governments, has historically focused on the provision of social and affordable housing, rather than barriers to more market housing. For example, in a keyword search of 268 AHURI research papers published between May 2011 and April 2025, ‘social housing’ appeared 44 times, ‘homelessness’ 28 times, and ‘affordable housing’ 24 times—but ‘housing supply’ appeared just seven times and ‘planning’ just six.

Whereas the federal government’s National Housing Supply and Affordability Council has not, in the nearly two years since it was established, undertaken the kind of in-depth research into what exact policy levers could be pulled, and how, that’s needed to unlock more housing construction.

The result is that the federal government lacks the expertise it needs to properly design incentives for state governments to build more homes, and for states to adopt them.

The federal government should establish a new housing research function within the Productivity Commission. Ultimately reforming state and territory planning systems will be an endeavour of the same scale as dismantling trade protectionism in Australia.

The Productivity Commission should publish annual statements assessing the permissiveness of state planning regimes. Those assessments should track whether planning controls add to the cost of homes in excess of the costs of building more.26

The Productivity Commission should also regularly advise the federal government on other policy reforms that would boost commercially feasible housing capacity, such as relaxing minimum car-parking requirements, reforms to apartment design guides (including minimum apartment sizes) and reforms to the National Construction Code.

And the Productivity Commission should assess whether state planning regimes allow for sufficient commercially feasible capacity to meet at least 30 years of expected demand for housing, as the New Zealand government requires of their local councils today.

When we have a shortage of electricity, everyone knows, because we have a blackout. It’s one the reasons the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) is regularly tasked with assessing whether there is sufficient energy supply in the pipeline to meet forecast demand. But when there’s a housing shortage, it’s less obvious, except to the poor and the vulnerable, who stand to lose the most.

Conclusion

The regulatory system that determines where people can live and work is one of our nation’s most fundamental. And yet for decades, this system has escaped scrutiny from those outside the silo of local councils and state planning departments.

The result is a regulatory approach across Australian states and territories that has failed to properly examine the consequences of the restrictions that it imposes on the lives of Australians, including scarce and unaffordable housing, a less dynamic economy, and a less equal society. The weight of evidence has become impossible to ignore.

Thankfully, the politics of planning are shifting. Legacy planning shibboleths are being upended daily in Victoria and NSW as state governments override commonly held beliefs, and the vocal objections of local residents, to permit more housing.

But there remains much to be done. And it will require all levels of government to play their part.

Key recommendations

To deliver the change needed to build more homes and deliver better cities, state & governments (recommendations 1 to 8) and the federal government (recommendations 9 to 11) must work together across four areas.

Relax state and local government planning controls that prevent density

Recommendation 1: Adopt a Low-Rise Housing Standard, which permits three-storey townhouses and apartments on all residential-zoned land in capital cities, with no minimum lot sizes.

Recommendation 2: Adopt a Mid-Rise Housing Standard, which permits at least six-storey developments on all residential-zoned land within walking distance of transit hubs and key commercial centres.

Recommendation 3: Identify and upzone other high-demand locations for even higher densities, including land in and around the CBDs of capital cities.

Recommendation 4: Review systems of heritage and character controls to allow more housing in high-demand areas.

Improve consistency and certainty in approval processes

Recommendation 5: Modest-density developments (i.e. up to three storeys) should be able to get certified as ‘complying’ instead of needing a planning permit.

Recommendation 6: There should be a ‘deemed-to-comply’ pathway for higher-density developments.

Fix planning governance

Recommendation 7: Subject changes to planning rules to regulatory impact assessments and existing planning controls to periodic review.

Recommendation 8: Set and enforce higher housing targets for local councils, where there is substantial unmet demand for housing.

Recommendation 9: The federal government should ask the Productivity Commission to regularly assess the performance of state and territory land-use planning systems, including through regular assessments of commercially feasible capacity for new homes.

Sharpen federal incentives to the states

Recommendation 10: The federal government should pay the New Homes Bonus in installments rather than at the end of the five-year period.

Recommendation 11: The federal government should pay the states, via National Competition Policy, to adopt specific reforms to land-use planning controls, including the standards outlined in recommendations 1 and 2.

For instance, in the areas of Auckland with the most permissive zoning, the cost of housing floor space per square metre does not rise as land values increase in areas with the most permissive zoning.

Other policy changes that would also make housing more affordable in Australia include removing barriers to greenfield land supply and better pricing of infrastructure, dealing with the shortage of skilled workers needed to build more homes, tax reforms including swapping stamp duty for broad-based land taxes, taxing the land value uplift from rezonings and reforming the capital gains tax discount and negative gearing, and the provision of housing assistance to vulnerable groups via raising Rent Assistance and building more social housing. Past Grattan Institute work shows that slowing the pace of migration would reduce house prices and rents somewhat, but would also leave Australians poorer

Other stated goals include managing population growth, limiting urban sprawl, and protecting biodiversity and heritage. Capturing part of the land-value uplifts associated with new development rights or public infrastructure investments is often argued to be an objective of planning.

Planning systems and the controls used vary across states and territories. See Figure 2.1 in Grattan Institute’s More Homes, Better Cities report.

Throughout this essay ‘residential land’ means established land where housing is permitted in some form. This includes mixed-use areas but excludes land zoned for greenfields expansion, unless stated otherwise.

One recent assessment estimated that 73 per cent of residentially-zoned land in Brisbane is zoned for low-density (generally two storeys or less). Whereas the Queensland Productivity Commission estimates that just 10 per cent of Brisbane is zoned medium density or higher.

Brisbane also uses a ‘traditional building character overlay’ which is less restrictive but more expansive.

See Box 2 in the More Homes, Better Cities report. Both the NSW and Victorian governments are currently expanding access to streamlined pathways for planning approvals.

However Victoria is implementing a new system that will restrict third-party appeal rights to higher-density apartments and to people directly affected.

See Grattan Institute’s More Homes, Better Cities report, Appendix B.

For example, see Cheshire and Sheppard (2002), Glaeser et al (2005), Turner et al (2014), Gyourko and Molloy (2015), and Rollet (2025). And cost-benefit analyses of reforms to relax restrictive planning controls in New Zealand found that the benefits substantially outweighed the costs.

For example, Rollet (2025) showed that more than 15 per cent of sites in New York City that increased the allowable floor-space ratio by more than two were redeveloped over two decades. This compared to less than 5 per cent of sites that had an increase of less than one.

The New Zealand government will soon require councils to “live-zone” sufficient capacity for 30 years of “feasible” housing, up from 3 years currently.

Although exceptions could remain for developments on sites that are subject to additional protections, such as heritage, bushfire or flood.

Figure 5.7 of Grattan Institute’s More Homes, Better Cities report shows three-storey townhouses could be profitably built on more than 40 per cent of sites covered by the Low- and Mid-Rise Housing Policy in Sydney, compared to just 20 per cent of sites if only two-storey townhouses are allowed, after accounting for the costs of acquiring and demolishing any existing buildings on these sites.

See Grattan Institute’s More Homes, Better Cities report, Figure 5.8.

For example, Rollet (2025) showed that more than 15 per cent of sites in New York City following rezonings that permitted an increase in the floor-space ratio of more than two above that of the existing building were redeveloped over two decades, compared to less than 5 per cent of sites that permitted less an increase in the floor space ratio of less than one.

For more details, see Chapter 4 of Grattan Institute’s More Homes, Better Cities report.

Before the reforms, central Auckland had zoned capacity of about 1.5 times the existing population. Yet housing was still scarce and expensive, because much of that capacity was in low-demand areas where it wasn’t profitable to build, or where existing homeowners were unwilling to move. Auckland’s reforms increased zoned capacity by 60 per cent — the equivalent of the total existing dwelling stock.

Past Grattan Institute work showed that if the 1.2 million home target was sustained for a full decade, rents could fall by 8 per cent, saving renters $32 billion over those 10 years.

For example, the NSW government would qualify for the New Homes Bonus payments for any extra homes built beyond a baseline of 314,000 homes over the five years by end-June 2029.

Reserve Bank researchers estimate that every 1 per cent rise in real interest rates lowers housing approvals the following year by 7 per cent.

Alternatively, payments could be made via a separate Federal Financial Agreement on housing between federal and state governments.

The payments could be set based on the boost to GDP and federal government tax revenues that is expected from the reforms. Alternatively, payments could be benchmarked to the increase in commercially feasible capacity for new housing.

See Valiente et al (2024) for a discussion of potential indicators to evaluate restrictions on urban land supply.

Great piece that confirms the wildly held view that state govt and councils bottleneck with zoning restrictions. Let the market decide how and where to build to give people more choice on type of housing and avoid the 2 hr daily driving time to commute to and from work. Density isn’t a killer of cities but an asset to culture and social fabric.

https://heathsteadco.substack.com/p/housing-is-broken-everywhere-why