Industrial Policy for Tech Workers

Australia has the opportunity to become the best place in the world to build the companies of the future.

This essay appeared in edition two of Inflection Points. You can listen to Brandon Sheppard discuss his essay and how Australia builds a successful tech sector on the latest episode of the Inflection Points Podcast, wherever you get your podcasts.

By Brandon Sheppard

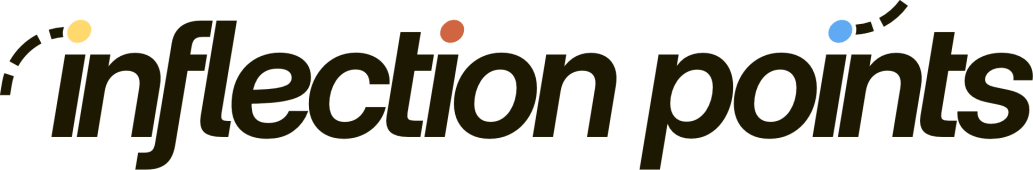

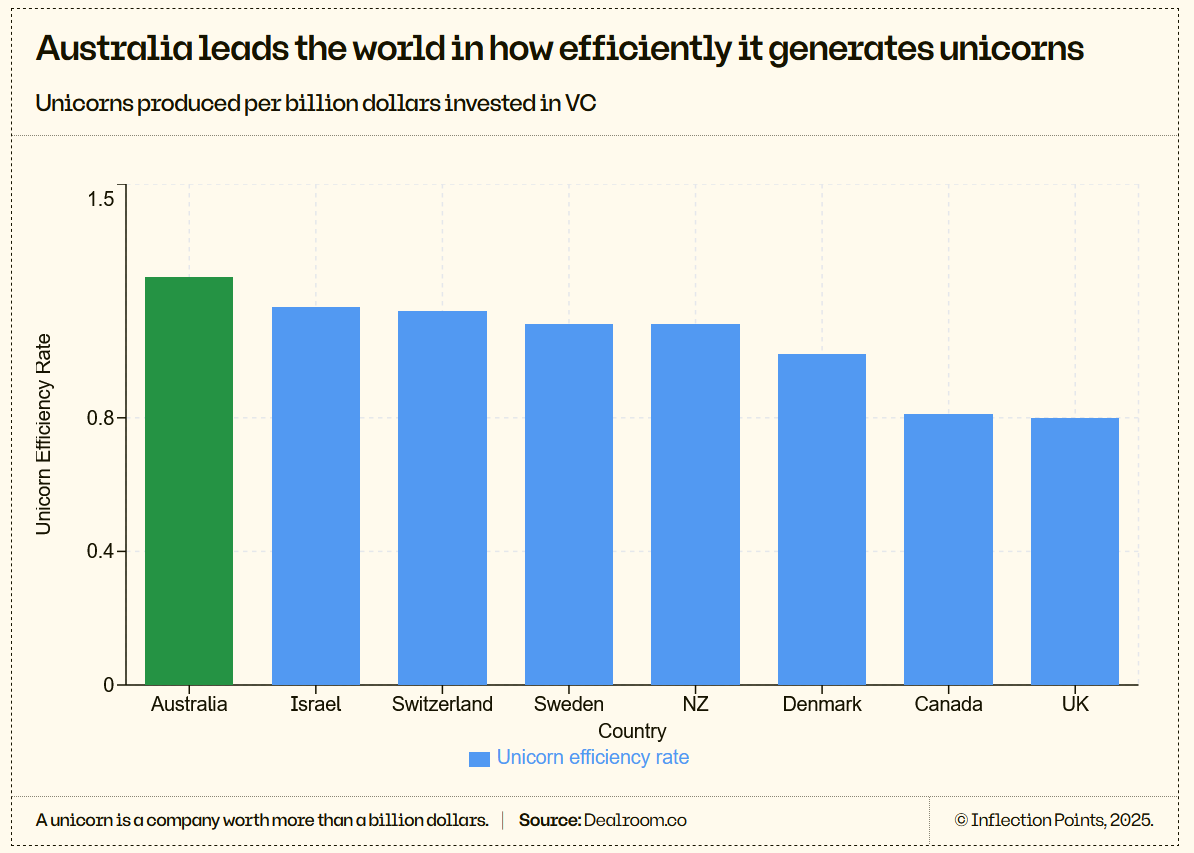

Australia has the talent, capital and ambition to build world-class software companies. By several measures we’re already punching above our weight: according to Dealroom’s 2025 Startup and Venture report, Australia’s $360B tech ecosystem is the second-fastest-growing globally, first in unicorns created per VC dollar invested, and top-five worldwide for decacorn creation.1

What we lack is a policy stack designed for how modern software is actually built and sold. Too many of our rules were written for labs and property syndicates; they reward paperwork over product, certainty over experimentation, and incumbency over mobility. And because our domestic market is small—too small to mint unicorns on local demand alone—founders must sell into markets like the US to scale, which too often leads great Australian companies to gradually become American ones. The result is predictable: founders incorporate here but scale somewhere else, employees sit on paper gains they can’t realise, and early-stage capital drifts to assets that are easy to hold and easy to sell.

I’ve spent over a decade building software companies here in Australia, working across Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane, and selling into the US market. Today I’m COO at Instant, one of the country’s fastest-growing startups, but my experience stretches across three ventures that all scaled into the USA and were funded or acquired by the likes of Oracle, Telstra, Blackbird, and Hummingbird. Along the way I’ve advised founders and operators across the ecosystem, and have seen up close the patterns that enable Australian companies to go global—as well as the frictions that push them offshore. The arguments in this essay come from years of shipping products, hiring teams, raising capital, and trying to keep the wins onshore. My perspective is shaped by building in Australia while competing in the most demanding markets abroad. And my passion comes from a belief that we, as a nation, can do even better. And in the global context of the United States’s great risk of brain drain, now is the time for Australia to capitalise, and create the best system possible for building the companies of the 21st century.

I can tell you from experience: Australian startups don’t need bigger cheques so much as fewer friction points. A more competitive software economy can be powered by five flywheels that reinforce one another:

Research and development incentives that are simple to claim and aligned to iterative product work

Broad employee ownership that turns staff into partners

An angel market that seeds the next generation

Talent that can move quickly to the teams shipping value, and

A pipeline that brings great engineers to Australia and grows more of our own

None of these changes require spending more; they require spending smarter—trading red tape for clear rules, and rigidity for trust paired with targeted safeguards. Do that, and Australia won’t just keep startups at home; we’ll help them win globally from here.

Modernise and simplify the R&D Tax Incentive for software companies

The Australian Government’s R&D Tax Incentive, a generous scheme that lets companies claim cash refunds or tax offsets on certain “eligible” research and development, is rightly promoted by the Australian Taxation Office as its “most significant lever for funding innovation and R&D”. For early-stage companies, it can be a great incentive to build in Australia: in practice, a loss-making startup that spends $1 million on eligible R&D can receive a cash refund of up to $435,000.

Despite the generosity, the program has significant problems, and provides limited benefit for smaller, early-stage firms due to high levels of administrative burden, including excessive documentation requirements and complex eligibility requirements.

To qualify, startups must prove their work is genuinely scientifically or technologically new, treating it as lab work by documenting formal hypotheses, methods, and results for each attempt. Companies must also separately track related costs, often via timesheets that require developers to track how long each task takes them—an approach long abandoned in modern software teams. This level of record-keeping diverts resources from actual innovation, and is at odds with modern product development practices, where teams work in short cycles, constantly iterating and adapting rather than running big linear projects. The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI) explicitly observes that “policy frameworks tend to treat research and development as a single linear process”, whereas in reality innovation often occurs “independently or in parallel”. In practice, many breakthroughs arise from routine development. For example, a major new feature might be discovered while fixing an unrelated bug. But innovation patterns like this are difficult to retroactively document to the R&D Tax Incentive program’s standards.

Even when software improvements are incremental rather than revolutionary, they can still create substantial economic value once they are brought to market—and this is especially true when developed in Australia and sold globally.

Credit the R&D Tax Incentive as a portion of total spend

A simpler model that allows companies to claim a reduced percentage of their total product development spend (instead of claiming individual qualifying tasks as per the current system), eliminates the need for granular timesheets, and streamlines documentation requirements, would make the program far more accessible. This approach would cut unnecessary bureaucracy, lower compliance costs, and enable more startups to participate, consistent with ACCI’s call to “[simplify] administrative processes to better support growing businesses and SMEs.” It would also better reflect the reality of how software is built, recognising that innovation often emerges from incremental work rather than formal experiments (a point ACCI makes in urging governments to “[acknowledge] that research and innovation are not always linear”). By shifting the focus from proving novelty to encouraging investment in local development, government support would capture a broader base of valuable activity without increasing public expenditure. In turn, this would help keep product development anchored in Australia, increase the number of companies able to scale globally from here, and deliver stronger long-term innovation outcomes at no extra cost to the government.

Encourage employee share option plans with simplified regulation

Today, most startups provide employees with company shares, typically through employee share option plans (ESOPs). ESOPs are one of the most powerful tools available to early‑stage software companies. They align incentives between founders and employees, attract and retain talent when cash is scarce, and reward the people who take the biggest risks in building something from nothing.

Researchers at Stanford University found that stock options attract “highly skilled and risk‑tolerant employees who are willing to sacrifice current salary for the potential of much larger future pay” and serve as retention tools. ESOPs also create a virtuous cycle: employees who share in a startup’s success often reinvest in the ecosystem, either as angel investors or by founding new ventures. As per European venture capital firm Index Ventures, in the US “thousands of employees across hundreds of startups have benefited financially following company exits” and many have gone on to become founders or angel investors themselves. A well‑structured ESOP not only helps early‑stage companies attract and retain talent but also creates a flywheel effect, enabling today’s team members to become tomorrow’s founders, investors, and mentors. This multiplier effect is how Silicon Valley has built its dominance on a culture of broad employee ownership.

Australia’s ESOP framework has improved significantly in the past decade, but it is still less competitive and less accessible than it should be. Recent reforms introduced by the Treasury Laws Amendment 2022 aim to “decrease red tape” for companies that issue shares or options, making it easier for startups to issue shares and “attract and retain talent”. These reforms expand the scope of eligible participants beyond employees and directors to “cover all people who provide services to a business”, remove cessation of employment as a taxing point, and eliminate onerous disclosure obligations for eligible schemes. Under the existing startup tax concession, qualifying companies can issue options that are taxed only at sale and at favourable capital‑gains rates.

In some ways, this is more attractive than the US system.2 But Australia’s scheme remains hamstrung by complex compliance requirements, creating a trade‑off between tax efficiency and legal simplicity. Put simply: Australian rules make it extremely difficult to offer the traditional ESOP structures that built Silicon Valley.

Australian founders have two different ESOP pathways. There is the easy way, which is simple to set up but for employees is taxed as income. And then there’s the hard way, which involves onerous disclosure, personal liability, and valuation requirements. This forces founders to choose between tax‑deferred options with an exercise price, which trigger heavier disclosure obligations, and zero‑exercise‑price options (ZEPOs), which are simpler to grant but taxed less favourably, and are therefore less enticing for employees.

The result is an ESOP program that is harder to implement than it needs to be. Even small early‑stage companies often require expensive legal and tax advice to navigate valuation, disclosure caps, and Corporations Act limits. The US, by contrast, allows companies to grant options widely with minimal paperwork under Rule 701. Australian companies that outgrow the startup concession’s criteria (notably the $50m annual turnover limit) lose access to its best tax treatment while still competing globally for talent. This forces many to ration equity or exclude junior staff from ESOPs altogether—the exact opposite of the broad participation that makes these offerings most valuable.

Broaden employee share option plan accessibility by focusing on a single turnover test

If Australia wants to match or surpass the US in early-stage competitiveness, our ESOP offerings must be simpler, broader, and more flexible. The first priority is to allow zero-exercise-price options and performance rights to qualify for tax deferral, so employees are not hit with income tax before liquidity. We should also remove the $50 million turnover cap, letting more scaling companies continue to use the startup concession.

At the same time, we need to reduce the administrative burden by creating a clear safe harbour — for example, allowing grants up to a fixed percentage of capital each year without triggering prospectus-style disclosure obligations. Finally, the $30,000 regulatory cap on grants should be lifted substantially so startups can make meaningful offers to key hires.

When more Australians own equity in the companies they help build, they are more motivated to deliver outsized results, and the returns they realise will seed the next generation of startups — a compounding advantage no grant program or tax credit can match.

Create an angel investing boom

Angel investing, when individuals use their own money to back a fledgling company, is the seedbed of a healthy startup ecosystem. It is how most world‑class startups begin: friends, colleagues and former co‑workers pooling small cheques into a founder’s early idea.

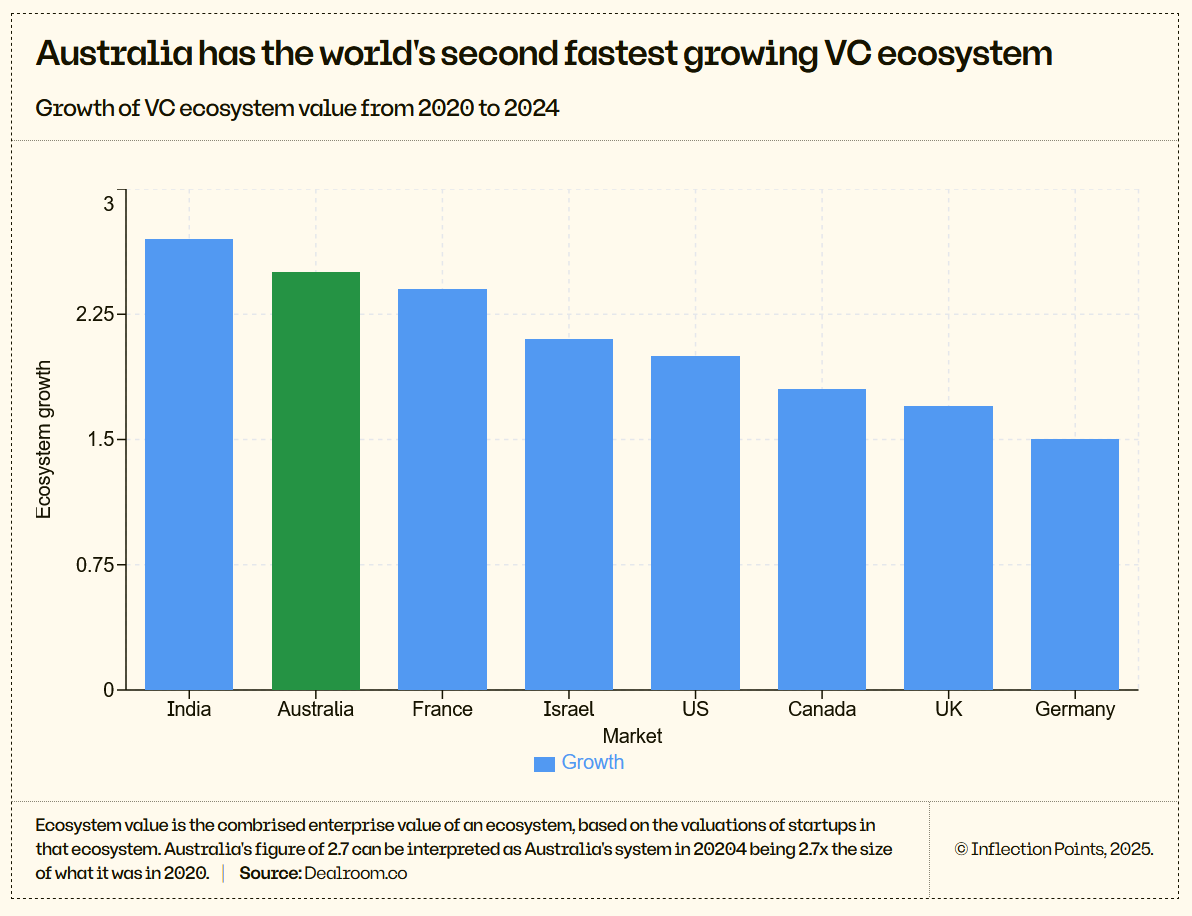

Angel investors are often themselves entrepreneurs and startup employees who invest their own wealth at the pre‑seed stage when startups have no revenue, providing strategic advice, resources and network access. For early‑stage software, angels are uniquely valuable: they bring operator experience, move faster than institutions and invest when banks and venture capitalists will not. Being an angel investor is also a way for startup employees to diversify their risk: if their own employer fails, they may still win from a friend’s company taking off. The effect compounds over time as employees who profit from an angel investment often reinvest into new ventures or found their own, creating a virtuous cycle of capital and experience that strengthens the entire sector.

Australia has the talent and private capital to domestically fund early‑stage investing, but investors are blocked from doing so by rules designed for property syndicates and passive funds, rather than modern software startups. And based on current policy trajectories, things are likely to get worse rather than better for angel investors.

Proposed superannuation taxes on unrealised gains threaten angel investing activity

The proposal to tax unrealised capital gains inside superannuation above a $3 million balance (Division 296) is a direct threat to angel activity.

Self‑managed super funds are a vital source of patient capital for small growth companies, and taxing unrealised gains would force trustees to de‑risk by shifting capital from unlisted, higher‑growth companies into liquid assets like property or listed shares. Paying tax on paper gains could require investors to sell holdings early, creating a success penalty and structurally shallowing the pool of angel capital.

Many angels invest through self‑managed super funds because it allows them to put long‑term, patient capital into local startups. Where holdings appreciate on paper before an opportunity to sell, a tax bill can create serious liquidity problems for angel investors. This liquidity mismatch will push capital away from Australian startups and into liquid assets like property or foreign shares. We should carve out unlisted, illiquid growth assets from Division 296 entirely, or at minimum defer any tax until a realisation event.

Wealth and investor testing locks many would-be angels out of the startup ecosystem

Equally damaging is the “sophisticated investor” wealth test. At present, Australians must earn $250,000 per year for two years or hold $2.5 million in net assets to invest in many early‑stage opportunities. This is already an extremely high bar, and the current government is considering raising it to $450,000 and $4.5 million, locking out even more potential angels. Parliamentary evidence shows the wholesale investor and client tests also operate as barriers to protect retail investors, requiring more disclosure and responsibility from providers when offering high‑risk investments and aiming to ensure that clients have appropriate financial knowledge and capacity to absorb losses.

These onerous gates were designed to protect people from scam property schemes, but in practice exclude the very operators we need: experienced software engineers, product managers, and startup executives who understand risks and are able to write meaningful cheques. A carve‑out for startup investing—either eliminating or significantly lowering the wealth test—would unlock thousands of new angels. Cheque sizes could scale with income or liquid assets—offering more options and opportunities than the current blunt limit on investment.

High compliance costs disadvantage new companies

Australia’s angel market also faces well-documented friction points beyond superannuation and wealth tests. The Early Stage Innovation Company (ESIC) tax incentive—a program that reduces an individual investor’s tax bill when they back very young Australian companies developing new products—is overly complex, with Azure Group, Chamberlains, and William Buck all pointing to the threefold problems of endless paperwork, uncertainty, and compliance costs. Investors often cannot tell if a company qualifies at the time they’re writing a cheque, and the professional advice needed to confirm eligibility can consume most of a small investment—while common company structures like an Australian parent with a US subsidiary can miss out entirely.

At the same time, Simple Agreement for Future Equity (SAFE) notes were designed in Silicon Valley as a standardised contract for early-stage funding, so investors could back startups quickly without heavy legal review. In the US, this standardisation has transformed the ecosystem: 88% of pre-seed rounds in 2024 used SAFEs, allowing deals to close in weeks instead of months, lowering legal costs, and broadening participation. In Australia, by contrast, SAFEs remain fragmented and inconsistent, which forces angels to pay for bespoke legal review and often excludes ESIC benefits because SAFEs don’t count as equity until conversion. The result is slower, more costly deals, and less capital flowing into local early-stage startups. Platforms like Birchal have already called for a standardised SAFE and retail investor access.

The fixes are straightforward—simplify ESIC with a checklist model, standardise SAFE notes, and align both systems with existing tax incentives—but the bigger opportunity is for government to work directly with angels, founders, and platforms to design solutions that reflect how startup investing actually works, in order to keep more early capital onshore.

Stimulate talent mobility in early-stage companies

Markets with greater workforce mobility, where people and employers can change jobs, teams, or working arrangements more easily, tend to produce better startups and attract more investment. As the Institute for European Policymaking lays out, restructuring costs increase very quickly alongside levels of labour protection. Australia is used as an example of this phenomenon: when it tightened dismissal laws in 2009, it shifted from “Denmark-type [employment protection laws] to a model closer to France or Italy”, causing firm productivity to fall by 1.2% on average, with wage growth suppressed as a result.

This high cost of adjustment shapes innovation choices: on the firm level, high firing costs tends to lead R&D investment to be directed toward mature products rather than new ones. On the macro level, countries with higher levels of labour protection tend to specialise in established industries, and leave innovation to countries with less employment protection.

For young startups, this creates a massive competitive disadvantage when stacked against US companies. Venture capitalists recognise this and avoid strict labour markets, to such a degree that the effect is measurable: early-stage company restructuring costs that equal four months of pay in the US equate to two years in Europe. In the US, a company can launch five projects, fail on four, and still profit; in Europe, the same sequence results in major losses.

Startups that do succeed in going global quickly discover the difference. Local companies that expand to the US see first-hand how flexibility changes their cost base. At-will employment means either the employer or the employee may terminate the relationship at any time, with or without cause, and with or without notice, and employers can adjust people’s responsibilities as the needs of the business change. In Australia, by contrast, it is much harder to change people’s responsibilities, move someone on after probation, or adapt arrangements at short notice. Yet governments are doubling down. Victoria is moving to legislate a right to work from home two days a week, while federally the Right to Disconnect gives employees the legal right to ignore work communications outside ordinary hours. These reforms may make sense for large employers, but founders have told me that they are already concentrating more hiring in the US, where the cost of a hiring mistake is far lower than in Australia.

Early stage startups should be able to fire faster

The truth is that early-stage startups need more flexibility, not less. It often takes several attempts to assemble the right mix of people, and roles evolve as the company learns what customers will actually pay for. Giving startups room to pivot benefits employees as much as companies: mismatches are resolved sooner, talented staff can land in teams where they grow faster, and new ideas can reach market even when they compete with a former employer. Australia already recognises this principle in a narrow way: under the Fair Work Act, employees must work for six months before they can file for unfair dismissal, and for small businesses with fewer than fifteen staff, that threshold is twelve months. Extending that full twelve-month period to startups with fewer than fifty employees would give founders a realistic timeframe to assess fit while building their foundational team.

Similarly, restricting most non-competes, as is proposed to soon be law, would empower talented staff to leave low-innovation firms and build something better, just as in California. The policy goal should not be to strip protections from workers altogether, but to create targeted exemptions for small, young startups, paired with clear choice: anyone who wants stronger protections can work at a larger company. That would boost mobility, accelerate the diffusion of skills, and strengthen Australia’s ability to build a globally competitive software industry.

Expand engineering talent pipelines

High-skilled migrants are outsized drivers of innovation. Research shows that, in the United States, immigrants make up just 16 per cent of inventors yet account for 23 per cent of patents, and their work produces larger spillovers for collaborators than that of native-born inventors. They are disproportionately likely to cite foreign research and collaborate internationally, seeding new networks of ideas. Research has shown that a ten-point increase in the share of H-1B workers at a firm boosts product reallocation rates by two per cent, a clear sign of faster innovation. Across the economy, high-skilled immigrants now represent roughly a quarter of the US workforce in innovation and entrepreneurship, and their contribution to patents and new ventures has grown steadily over the past three decades. The economic dividends are unmistakable: each one per cent rise in employment driven by immigration increases income per worker by nearly half a per cent. It is no surprise then that nearly half of Fortune 500 companies in 2024 were founded by immigrants or their children, together employing 15.5 million people and generating US$8.6 trillion in revenue.

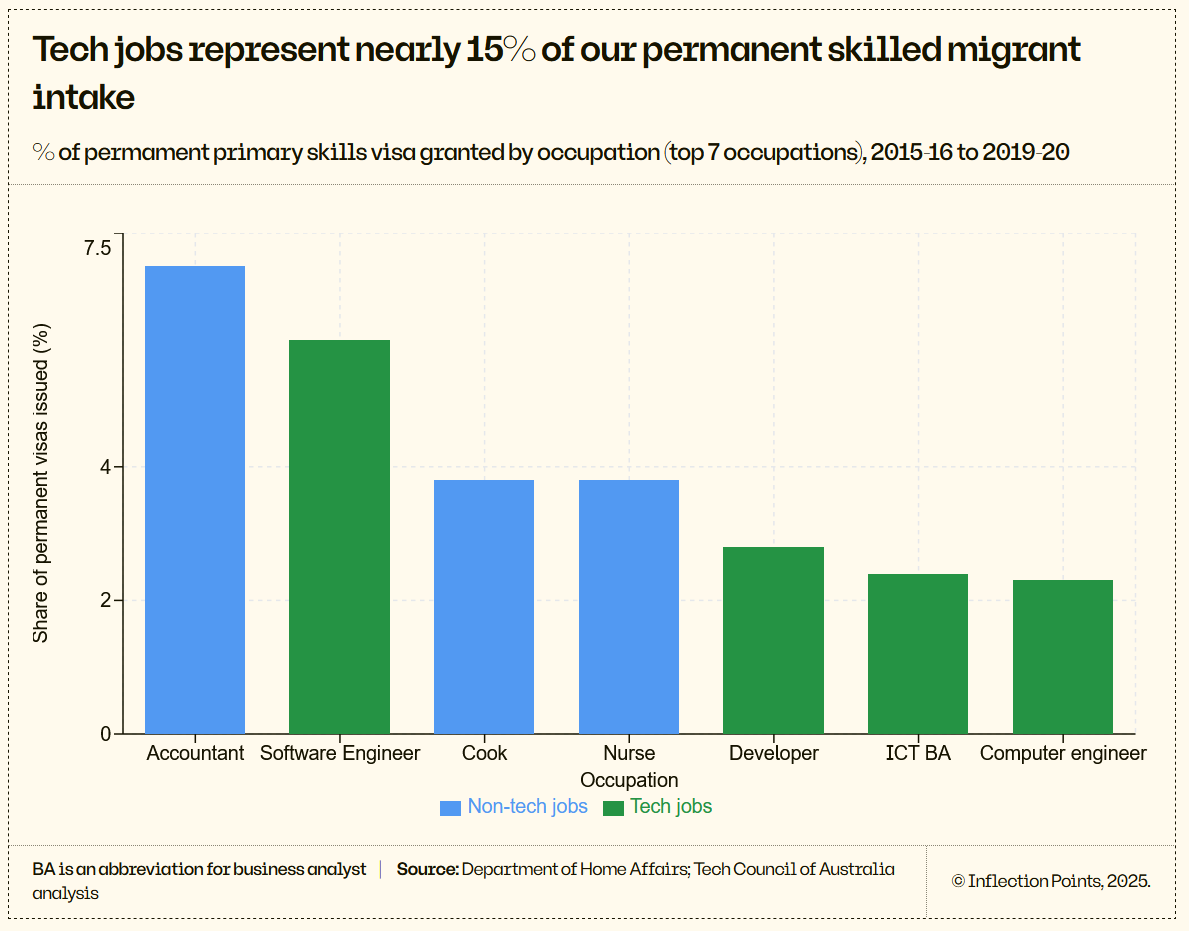

Australia already knows this story firsthand. Nearly 45 per cent of the domestic technology workforce was born overseas. In software specifically, the share is even higher: two-thirds of Software and Applications Programmers are migrants. Engineering tells the same tale—between 2016 and 2021, 70 per cent of the growth in Australia’s engineering labour force came from overseas-born engineers. The reality is that Australia’s innovation economy is already powered by migration; the question is whether we can keep attracting the people who will power its future.

Yet our system is still designed to frustrate precisely the kind of people who could make the biggest difference. Most skilled workers come through the points-tested system, but for startups the employer sponsorship pathways are the most direct lever—and also the most broken. The new Specialist Skills Pathway is a step forward, with an aspirational seven-day processing target. Its salary threshold of $135,000 (rising to $141,210 on 1 July 2025) is defensible in principle, because salary is a far better quality filter than occupation lists or skills assessments.

But for many startups it is still set too high, cutting them off from hiring skilled engineers at competitive but slightly lower salaries. Worse, the pathway is capped at just 3,000 places and remains entangled in uncertainty: employers must still wade through occupation codes, skills assessments, and labour market testing, hurdles that add friction long before any application reaches a case officer. On top of that, nomination fees, visa charges and the Skilling Australians Fund (SAF) levy—which alone can run from $1,200 to $7,200 per worker—make sponsorship prohibitively expensive. Add migration agent costs and the true burden often exceeds $10,000 per hire.

Other countries are not standing still. Europe has launched its €500 million “Choose Europe for Science” initiative to lure displaced researchers and entrepreneurs, backed by the €93.5 billion Horizon Europe program. The United States, once the unrivalled magnet for talent, is faltering: President Trump’s September 2025 order effectively bars entry for new H-1B workers unless employers pay a punitive US$100,000 fee. With American universities and firms suddenly less welcoming, a once-in-a-generation pool of global talent is searching for alternatives. Europe is competing aggressively. Australia risks squandering the opportunity.

For Australia to lead, it must be assertive about attracting international talent

A bolder strategy is needed. The Specialist Skills Pathway should be expanded into the default entry point for global tech talent, with the salary threshold and employer sponsorship treated as proof enough of ability, while lowering the threshold moderately so it aligns better with startup salary realities. Labour market testing, occupation lists and skills assessments should be abolished altogether for high-skill roles, shifting compliance to audits rather than upfront hurdles. Sponsorship fees and levies should be cut or waived, making it truly affordable to hire globally. All these costs should be cut dramatically, with the SAF levy waived for startups, so that bringing in a brilliant engineer from Bangalore is no more expensive than from Brisbane.

And instead of passively processing applications, Australia should actively court world-class researchers, entrepreneurs, and students through a dedicated Global Talent Attraction Office, offering relocation support, research chairs and co-investment in promising ventures. At the same time, visas like the National Innovation Visa should be simplified and expanded, with clear pathways to permanent residency for those who meet salary or startup success benchmarks.

The case for urgency is simple. Every study confirms that high-skilled migrants increase productivity, create jobs and accelerate innovation. Every month that Australia dithers, those people take their ideas elsewhere. Just as Silicon Valley’s dominance rests on a virtuous cycle of immigrant talent reinvesting in the ecosystem, so too could Australia harness this flywheel—if only it were willing to clear the bureaucratic hurdles and compete.

Conclusion

After more than a decade building Australian startups, I’ve seen the same pattern play out again and again. The builders here genuinely love this country. They want their companies, their IP, and their wins to push Australia forward. Yet I’ve also watched idealistic founders slowly lose faith that they can truly build it all here; the frictions add up, and before long they’re effectively building American companies — even when the founding story is unmistakably Australian.

It doesn’t have to be that way. Our biggest success stories, including companies like Canva, Atlassian, and Afterpay, were built here, and there are many more fledglings coming through. The system we’ve assembled for startups is, in many respects, enviable. With a handful of surgical changes, it could be the best in the world. The industry wants more of the value it creates to accrue to Australia; these simple recommendations would make that happen.

This essay sets out a practical modernisation program built around those flywheels. First, redesign the R&D Tax Incentive so it fits agile development instead of pretending every breakthrough comes from a lab notebook. Second, lift talent mobility where it matters most for young firms. Third, simplify and broaden ESOPs so more Australians own the upside they create. Fourth, unlock an angel investing boom by removing mismatched tests and liquidity traps. Finally, expand engineering pipelines with faster visas and work-ready training.

Brandon Sheppard is the COO of Instant. He has over a decade’s experience working in Australia’s tech sector.

A decacorn is a company worth $10 billion or more.

In the US, many employees get a tax bill when they turn options into shares, even though they can’t sell those shares yet, so they must pay in cash or risk losing them. Australia’s system avoids this pitfall.

Very good! Investing in startups should be made easier. It should be possible to distinguish between an elderly grandma, which needs protecting from con artists, and angels investors who understand the risk and can afford it. And anyhow, the people who really need the state to protect them are gamblers - not investors in startups.

Great read, agree with most of this, and have also lived a lot of the pain since moving back to AUS. The amount of time I've spent wrangling documentation for the R&D scheme is mind-boggling...