Diversifying Australian Risk Capital

Australian entrepreneurship isn’t hamstrung by the quantity of venture capital but by the kinds of risk capital available.

This essay appeared in edition two of Inflection Points. You can listen to Jessy discuss her essay and Australia’s VC sector on the latest episode of the Inflection Points Podcast, wherever you get your podcasts.

By Jessy Wu

Australia leads the world in Unicorn creation per dollar invested.1 For every $1 billion invested into venture capital in Australia, we birth 1.22 Unicorns—that is, a technology company that achieves a valuation over $1 billion. The United Kingdom lags with 0.8 Unicorns created per $1 billion invested, while the US only manages to mint 0.69 Unicorns per $1 billion invested.

Our ability to efficiently create tech Unicorns is a bright spot in an otherwise grim economic picture. The OECD downgraded Australia’s 2025 growth forecast to 1.8% warning of the risk of the slowest annual growth (excluding the pandemic period) since 1992. Between 2010 and 2020, Australia endured its weakest productivity growth in 60 years. On the Economic Complexity Index (ECI), Australia has fallen dramatically—from 63rd in 2000, to 93rd in 2021, and further to 102nd in recent updates.

Is the solution to our economic malaise to lean into what we’ve shown ourselves to be successful at in the past; to increase the amount of venture capital in Australia, in the hope we’ll mint even more tech Unicorns?

I argue that simply increasing the quantum of venture capital isn’t the solution. A more complete solution would be to increase the variety of capital available to new businesses; to make the market for a new cohort of fund managers to launch smaller, differentiated funds that can invest in a diverse range of innovative companies—not just those aspiring to become software Unicorns. To be clear, I’m specifically referring to funding for new and emerging companies, not mature businesses that have access to private equity or traditional bank loans.

Of course, this begs the question—if there’s genuine opportunity to invest in these overlooked businesses, why isn’t anyone capitalising on it? If large funds are leaving money on the table, why haven’t nimble new players spun up to capture these returns? In an efficient market, this gap would have been filled.

But currently in Australia, emerging fund managers face such prohibitively high barriers to entry that raising a fund to pursue these alternative strategies is at worst unviable, at best unattractive. This is one of the dynamics bottlenecking the creation of an innovation ecosystem where different kinds of businesses can access appropriate capital; which could in turn unlock a more dynamic and risk-taking society.

The solutions to this problem aren’t complex or necessarily expensive. Most of my recommendations urge governments to make tweaks to regulation and tax incentives, such as adjusting superannuation funds’ performance testing regime and making amendments to the Early Stage Venture Capital Limited Partnerships (ESVCLP) tax incentive program.

Emerging fund manager talent is there on the sidelines, but is being bottlenecked by high barriers to entry. Targeted support to overcome these initial barriers could go a long way; as would a privately-run VC fund-of-funds that could act as a market maker and on-ramp for emerging fund manager ambition.

Government attempts to deploy directly into venture capital have been vexed

Having the government directly invest in technology companies is a popular proposal. Melbourne University’s incoming vice chancellor Emma Johnston has called for the government to invest $1 billion into a venture capital fund deployed by universities, while Member for Wentworth Allegra Spender has petitioned the government to re-orient existing investment vehicles such as the $15 billion National Reconstruction Fund (NRF) to help catalyse Australian VC.

However, government-run venture capital funds are frequently vexed, because they’re trying to serve two masters: delivering financial returns while simultaneously fulfilling other policy objectives. Breakthrough Victoria, the Victorian government’s controversial $2 billion venture capital fund, illustrates this tension.

Since its establishment in 2021, Breakthrough Victoria has faced sustained criticism, which intensified after revelations that the fund spent $22 million on operating costs while deploying only $74 million in investments during 2023. As a point of comparison, privately run VC funds typically spend 2% of committed capital per annum on operations. Amid mounting pressure and the state’s rising debt burden, the Victorian government slashed the fund’s budget by $360 million over four years in the 2024 budget.

The fund’s 2024 investment in World View—a US start-up developing stratospheric balloons for sensing and communication services—exemplifies the problem with government-led venture capital funds. World View had recently terminated plans to merge with a SPAC in a deal that would have injected over $100 million, when Breakthrough Victoria stepped in with a $37 million investment, albeit with strings attached: World View was required to build “an advanced manufacturing facility that will ultimately employ up to 200 Victorians.”

But these kinds of funding conditions often lead to adversely selected investments. Companies with strong prospects can typically attract funding from sources that don’t impose operational constraints, meaning government funds may end up backing ventures that private capital has already passed over. By trying to achieve job creation and financial returns simultaneously, funds like Breakthrough Victoria risk achieving neither objective.

Rather than attempting to compete directly in venture capital markets, governments should focus on what they can uniquely do: creating the regulatory environment and enabling infrastructure that encourages private capital to invest in this asset class. Private fund managers, unencumbered by competing political objectives, can make investment decisions based purely on financial merit. This ultimately generates better outcomes for both entrepreneurs seeking funding and for the broader economy.

There is a growing amount of venture capital available, but it’s concentrating in a handful of large funds

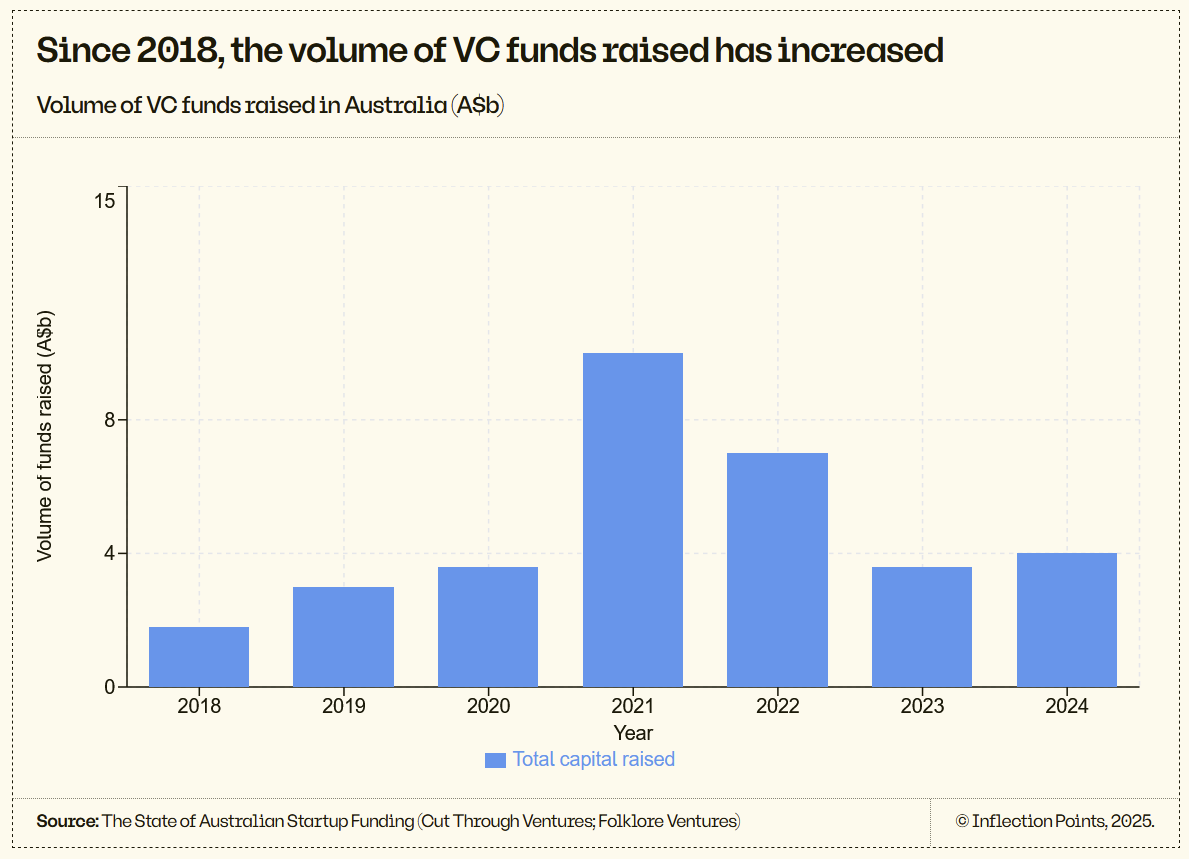

2024 saw $4 billion of venture capital raised by Australian startups across 414 deals. While this falls short of the $10 billion raised in 2021, it’s twice as much as the $2 billion raised in 2018. According to The State of Startup Funding Report compiled by Cut Through Venture, there was general optimism about the amount of capital available for startups and scaleups in 2025.

However, a large portion of this capital is starting to concentrate in three megafunds. Thanks in part to the standout performance of Canva, which received early investment from Blackbird Ventures, Square Peg Capital, and Airtree Ventures, these three funds now boast impressive historical returns. This track record has unlocked access to substantial institutional capital from both Australian superannuation funds and international investors.

In August, Airtree announced a $650 million fifth fund, with the majority raised from international investors: the institutional asset management arm of one of the world’s largest insurance companies, the endowment fund of Harvard University and the University of Wisconsin, as well as AustralianSuper and the Australian Retirement Trust. Blackbird Ventures has announced a first close on a $700 million sixth fund, while Square Peg Capital has been fundraising for a $840 million sixth fund.

According to Pitchbook data compiled for The Australian Financial Review, seven local venture capital firms successfully closed new funds in 2024, raising a combined total of $3 billion AUD. In 2023, 11 funds closed, raising $670 million AUD.

The 2024 figures are skewed by Breakthrough Victoria, which accounted for $2 billion of the $3 billion total. Excluding the government-backed fund, Australian VC funds raised approximately $1 billion in 2024, bringing the two-year total for private fund closes to just under $1.7 billion. If the “Big Three” succeed in reaching their target fund sizes, their combined 2025 closes would roughly equal this entire two-year total.

Large funds are incentivized to deploy quickly into cash-hungry businesses

Fund strategies are dictated by fund sizes. Venture capital funds are under pressure to deploy their capital within 3 - 5 years, which means large funds must prioritize finding cash-hungry startups that can absorb significant investment over a short timeframe.

The optimal investment becomes a company that can consume a large amount of cashover five years. This creates a bias toward capital-burning business models, favoring companies that can spend cash quickly to win market share over those that might be more capital-efficient but require smaller check sizes. Moreover, when large funds write substantial checks into late-stage companies that have already expanded globally, less of this capital flows into the Australian economy. Take Airwallex, which recently received significant investments from Blackbird and Airtree as part of its $300m funding round—despite being an Australian-founded company, the majority of its operations and workforce now sit outside Australia.

Fund economics reinforce this bias. When a $1 million investment represents less than 0.15% of a $700 million fund, the due diligence, board participation, and portfolio management work becomes unwieldy relative to the fund’s total assets under management. The same amount of time invested in a $50 million deal has 50 times the impact on fund deployment.

In addition, larger funds are also incentivized to deploy capital quickly so they can raise subsequent funds and grow their management fee base. Funds typically charge a 2% annual management fee on assets under management, meaning a $700 million fund generates $14 million in annual fees before any investment returns. Since management fees scale with fund size regardless of performance, there’s a financial incentive to prioritize speed of capital deployment to raise more large funds.

Critically, this comes with the exclusion of smaller funds that are tailored to the sorts of emerging businesses that their traditional funds. Large funds would rather specialise in what they now know – the established tech businesses that they came in at the ground floor at. Creating a parallel fund would require re-building well established fundraising and diligence processes (which their super funds and LPs are already comfortable with), alongside hiring many new investors. Put short: the effort to create smaller funds for the big three is too high, especially when there is so much money to be made in mega funds.

Large funds’ narrow and homogenous mandates exclude good businesses

As a result, Australia’s well-capitalised venture capital funds operate fairly homogenously, pattern-matching for the same narrow range of opportunities. This creates intense competition for deals within their limited mandate while also leaving vast swathes of the innovation landscape underfunded.

As their fund sizes have grown, the ‘Big Three’ Australian VC funds have increasingly converged on the same investments. All three funds are now invested in graphic design company Canva, fintech Airwallex, and AI customer service platform Lorikeet. In 2024, Airtree led SafetyCulture’s $165 million Series D round—a 21-year-old company that has been heavily backed by Blackbird since 2013.

If you talk to investors at these funds, they’ll admit they’re all chasing a similar archetype: high-margin, software businesses targeting global markets, often leveraging frontier technologies like AI. VCs favor companies that create defensive moats as they scale, leading to a winner-take-most dynamic where being the market leader compounds into an insurmountable advantage. The ideal investment can rapidly burn capital to capture market share, then convert that dominance into pricing power.

Competition for companies that match this mould can create suboptimal outcomes for the investors backing these funds (who are, often, the same super funds). When multiple large venture capital funds chase the same deals, they bid against each other, driving up entry prices and depressing overall returns. Superannuation funds invested across several of these VC funds may find themselves inadvertently competing against their own capital.

The concentration of capital into large funds also disadvantages capital-efficient businesses. Businesses that could grow with modest investment are unable to attract funding not because they lack merit, but because they cannot absorb enough capital to justify a large fund’s attention.

One category of business that struggles to find suitable funding is those that can reasonably expect to reach $20 - 50 million in annual revenue but require upfront investment for R&D, product development, or scaling operations. These might include niche software companies, consumer brands, lending businesses, or hardware manufacturers. Their return profile and modest capital requirements make them unattractive to large venture capital funds, while their lack of immediate profitability disqualifies them from bank loans. However, they can offer strong risk-adjusted returns for the right investor: one deploying patient capital in smaller amounts. Moreover, these businesses deliver significant economic value: they create quality jobs, inject competition into complacent industries, and drive innovation in underserved markets.

Barriers to entry for first-time fund managers pioneering new approaches are insurmountably high

Of course, where there’s a gap there’s opportunity. In an efficient market, you would expect smaller funds pursuing different strategies to emerge, filling the gaps created by large funds.

A smaller fund can invest earlier and write smaller cheques into businesses with more modest return profiles. After all, a $1 million investment for a 10% stake in a seed-stage company can return a $20 million fund if the company exits for more than $250 million, factoring in dilution along the way.

However, in Australia, several significant barriers are preventing first-time fund managers from entering the market:

Prohibitive fund economics. The traditional venture capital model operates on a “2 and 20” structure: a 2% management fee plus 20% of carried interest on fund returns. A $20 million fund generates only $400,000 in annual management fees, which must cover licensing, insurance, legal compliance, and accounting. Only individuals who can afford minimal salaries—or work without compensation—can realistically launch new funds under these constraints. While fee structures that provide a greater portion of fixed fees exist (like sliding scale fees and capped carry), these are yet to be adopted widely in Australia, likely due to the inexperience of LPs investing in these fund types.

Difficulty accessing institutional capital. Institutional investors, including Australian superannuation funds, typically require a minimum five-year track record before considering an investment in a fund. In addition, they often impose a minimum check size of $25 - 50 million, which can represent a significant portion of an emerging manager’s target fund size. What’s more, many institutional investors have a rule that their investment can’t represent more than 30% of the total fund, stemming from reporting regimes that discourage them from underperforming their peers. This creates a catch-22 for new fund managers: emerging managers need institutional capital to achieve scale, but they cannot access such capital without an established track record and large fund size.

The cost of failure is severe. Unlike companies that can be wound up, fund managers must manage assets for the decade-plus life of the fund, and do their best to return capital to investors. Failing to raise a subsequent fund traps managers in “zombie mode”—locked into managing their existing portfolio without fresh capital to deploy or meaningful income from management fees. This prospect of professional limbo deters talented individuals from this path.

Australian LPs are reluctant to back ‘unproven’ fund managers. Despite data showing that first-time managers often outperform established ones, Australian Limited Partners (HNWs and Family Offices) generally lack the appetite to back unproven fund managers; most prefer to see a track record before committing capital. This may be due to the fact that Australian LPs are investing generational wealth, rather than cash generated through high-growth tech businesses.

Regulatory adjustments can unlock more private capital for venture overall

To incentivise more private investment into venture, the government could adjust its current superannuation performance testing regime, which would enable Australia’s $4.2 trillion superannuation sector to increase its allocation to venture capital and private equity.

The regime was introduced in 2021 with good intentions: to eliminate the “entrenched underperformance” that had plagued the industry and protect members from poor investment outcomes and excessive fees. Under this system, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) annually measures fund performance against regulatory benchmarks, with severe consequences for failure. Funds that underperform must notify members, and those that fail twice consecutively are banned from accepting new members.

However, the testing regime has created unintended consequences and discouraged investment in certain asset classes. The annual assessment cycle disincentivises funds from pursuing active strategies that might temporarily underperform benchmarks. This has led to what critics describe as a “homogenisation of investment strategies“ where funds avoid anything that could cause short-term underperformance relative to listed market benchmarks.

The regime particularly penalises investment in illiquid, long-duration assets like venture capital, that may underperform in early years but deliver superior long-term returns. VC operates on a different timeline and risk profile than listed equities, following the “J-curve” performance pattern. Failures typically emerge first—often within the first two years as companies exhaust their initial capital. Winners become apparent next, usually between years three to five as companies gain traction. However, the true extent of winners—the outsized returns that drive overall portfolio performance—only materialises last, often eight to ten years after the initial investment.

Consequently, super funds that allocate to VC may underperform benchmarks for several years while their investments mature, risking severe test failure consequences despite pursuing strategies that could ultimately deliver superior member outcomes. The rational response has been to decrease allocation to venture capital, despite its potential contribution to both members’ returns and national productivity.

It is important that reforms do not dilute accountability. Scrutiny of superannuation performance must be maintained to protect members and ensure capital is managed responsibly. The challenge is not whether to scrutinise, but how. A regime that conflates short-term underperformance with long-term risk ends up discouraging precisely the kinds of investments (e.g., venture, infrastructure) that align with members’ long-term horizons. By recalibrating benchmarks to match asset-class characteristics rather than imposing a one-size-fits-all test, regulators can preserve discipline in the system while enabling super funds to pursue genuinely diversified, long-term strategies.

One approach would be to anchor performance to a risk-adjusted metric, like the Sharpe Ratio, as was considered by Treasury in its 2024 Consultation Paper. The Super Members Council estimates that reforming the testing regime could double superannuation’s allocation to private equity and venture capital from 6% to 10% over five years, directing approximately $50 billion toward innovative private companies. Given that Australia’s superannuation sector represents one of the world’s largest pools of patient capital, changing this testing regime could have a significant impact on the amount of private capital flowing into VC funds.

Emerging fund managers need better on-ramps

Currently, individuals must crawl over broken glass to become fund managers.

While some of the challenges are unavoidable or require cultural change, governments can do their part to increase the amount of private capital available for venture capital, reduce barriers to entry, and create a more robust pipeline for emerging fund managers pursuing diverse mandates and strategies:

Reduce the minimum threshold for an ESVCLP

In Australia, the Early-Stage Venture Capital Limited Partnerships (ESVCLP) program provides significant tax incentives to fund managers and investors. Investors enjoy tax-free treatment on income and gains, plus a non-refundable carry-forward tax offset of up to 10% of their contributions. However, funds need $10 million in committed capital to qualify for ESVCLP status.

The $10 million threshold locks out brand new fund managers from accessing the same tax advantages available to established funds. Without ESVCLP status, these small funds cannot offer competitive tax treatment to prospective investors, who understandably gravitate toward funds with better tax benefits. Lowering the threshold to $3 million would level the playing field, enabling promising emerging managers to compete on merit rather than being disadvantaged by unfavorable tax status.

The significant administrative burden should also be streamlined for smaller funds. Current reporting requirements were designed for institutional-scale funds and create disproportionate compliance costs for smaller operators. Simplified reporting for funds under $10 million would remove operational barriers that smaller funds often cannot afford to meet.

Increase targeted support for emerging fund managers

New fund managers incur substantial upfront costs before they can even begin fundraising—legal, compliance, and preparing investment documentation can easily cost tens of thousands of dollars. Support programs that provide funding for these setup costs make a material difference for new fund managers.

Victoria’ startup agency LaunchVic has pioneered the VC Support Program, which provides up to $300,000 to individual funds establishing themselves in Victoria. The program supports both new funds and existing managers relocating to Victoria, covering establishment costs such as legal fees, staff salaries, and capital raising expenses for funds aiming to raise a minimum of $10 million.

The program has already demonstrated success in fostering innovative fund strategies. Three recently launched funds—FB Ventures (VC that’s accessible to retail investors), Advance VC (a fund of funds focused on fund secondaries), and Ecotone Partners (hybrid debt-equity for climate companies) all received support from LaunchVic’s emerging manager program. These funds all exemplify diverse strategies that enrich the ecosystem: FB Ventures is allowing retail investors to gain access to VC funds, Advance VC is creating much-needed liquidity for fund investors, and Ecotone Partners is addressing the climate funding gap through combined debt and equity structures.

LaunchVic’s $2.1 million investment across seven emerging VC funds is a positive example of what can be unlocked through targeted support that slightly reduces the barriers to entry for new fund managers. Just $300,000 can provide resourceful and ambitious fund managers with the boost needed to establish operations and begin building track records that can subsequently attract private capital.

Encourage a fund-of-funds to act as a market-maker for fund manager ambition

As the ecosystem matures and more institutional capital becomes interested in the asset class, there may eventually be sufficient demand to support a VC fund-of-funds that acts as a market maker for emerging fund managers. Such a vehicle could pool capital from institutional investors seeking diversified exposure to venture capital, while providing a structured pathway for promising new managers to establish themselves and access larger pools of capital.

The model could operate in two phases: initially seeding individual managers with $2-5 million funds plus $300,000 in operating expenses, providing a two-year runway to deploy capital and demonstrate coherent investment theses. For managers who prove their approach, the fund-of-funds could then cornerstone a subsequent $10 - 30 million fund, serving as a market signal that the manager has been professionally vetted and battle-tested.

Competition between emerging fund managers would drive innovation across the sector, leading to a more dynamic ecosystem where emerging managers compete to find excess returns and establish track records. Different investment strategies could be tested, giving entrepreneurs greater choice when seeking capital.

This fund-of-funds would create a structured pathway for talented individuals to become fund managers without requiring personal wealth, while providing institutional investors with professionally vetted access to emerging managers who might generate superior returns. Rather than superannuation funds inadvertently competing against themselves by backing multiple large funds chasing identical deals, they could diversify across broader investment strategies and manager profiles, potentially improving overall venture capital returns while supporting a more dynamic ecosystem.

Importantly, this fund-of-funds should be managed by private sector professionals experienced in fund manager selection, incentivized through carry (upside participation) in the performance of the portfolio. Fund manager selection is a distinct skill—top-quartile fund-of-funds managers consistently identify emerging talent before institutional investors, often achieving superior returns by backing first-time managers who later become market leaders.

Promising international models include Allocator One, a European fund-of-funds headquartered in Germany. Founded in 2024 to address the barriers that first-time and second-time venture capital managers face in raising their initial anchor commitments, Allocator One positions itself as both an anchor investor and an accelerator. For fund managers, it offers between €1 million and €7 million in early commitments alongside intensive operational and fundraising support. Its twice-yearly 12-week batches are designed to help a select cohort of emerging GPs establish their funds efficiently, with guidance on everything from fund structure to LP introductions. Allocator One has already established a reputation for rigour and selectivity, reviewing hundreds of applicants but backing only a small fraction.

A diversity of risk capital would fund a greater variety of businesses

A greater diversity of funds pursuing different strategies would likely result in a broader range of innovative companies being funded. Many promising companies require capital, but aren’t chasing the winner-take-most opportunities which return megafunds.

For example, companies that can grow steadily to $20 - 50 million in annual revenue—and potentially exit through an acquisition, management buyout, roll-ups, or small-cap ASX listings—represent an underserved market segment. Rather than forcing these businesses to contort themselves into venture-backable narratives, alternative funding structures could provide more honest alignment between capital providers and business owners. Other innovative forms of risk capital include:

combined debt and equity funds, which offer flexible capital structures particularly suited to capital-intensive businesses. Rather than forcing companies to choose between dilutive equity or restrictive debt, these funds provide blended financing suited for a company’s particular phase of growth. For companies that need substantial upfront capital for manufacturing but generate predictable cash flows once operational, this approach reduces dilution while providing patient capital. Ecotone Partners recently raised $20 million from family offices and HNWs to pioneer this model for climate companies.

scout funds, which are an investment model where investors back individuals before they’ve formed companies or even identified specific opportunities. These funds essentially place bets on people, providing capital for promising entrepreneurs to explore ideas, conduct market research, and develop a ‘minimum viable product’. While relatively uncommon in Australia, scout funds are prevalent throughout the US; established VCs often allocate portions of their funds to scout funds. Some pre-seed funds such as Co Ventures behave like scout funds, backing individuals with small cheques while they’re still in ‘ideation’ stage.

search funds, which focus on identifying and supporting individuals to acquire and operate existing profitable businesses. The search fund model typically provides an entrepreneur with capital to spend 18-24 months searching for acquisition targets, followed by additional investment to complete the purchase and support operations. This approach targets the universe of profitable small and medium enterprises whose owners are ready to exit. Search funds are also well-established in the US, with dedicated programs at business schools and institutional backing, but remain virtually non-existent in the Australian market, despite the abundance of potential acquisition targets among family-owned businesses approaching succession decisions. Enduring Investments is an example of an Australia search fund that’s been founded recently.

These examples are not exhaustive by any means; they merely illustrate that a greater variety of approaches would better serve the broad spectrum of business opportunity that falls outside the narrow mandate of large venture capital funds, and create a more comprehensive launchpad for Australian innovation.

While green shoots exist—with newly founded funds like Ecotone Partners, Co Ventures, and Enduring Investments pioneering alternative strategies—each has faced significant barriers to entry. Some initially operated as advisory businesses, others have foregone market salaries to operate funds at sub-scale, and others have been able to get started by reinvesting exits from previous ventures.

To build an antifragile ecosystem, we need more structured pathways for emerging fund managers, with clear routes to accessing institutional capital for subsequent and larger funds. Rather than relying on individual resourcefulness to overcome barriers, we need policy frameworks and enabling infrastructure that make it not only viable—but attractive—for talented individuals to launch innovative fund strategies, without requiring significant personal wealth or professional sacrifice.

Conclusion

Venture capital in Australia is still nascent, and we should be proud of what we’ve achieved. We owe a great deal to the VC funds that built our current ecosystem and backed some of Australia’s great tech companies, including Canva, Airwallex, Rokt, and Go1.

While they deserve their success, the concentration of venture capital into a small handful of megafunds pursuing similar strategies is not the formula for a substantially more entrepreneurial and dynamic economy. Megafunds succeed by investing large sums into cash-hungry businesses chasing global markets where winner takes most—they’re not suitable funders for the vast majority of Australian innovators who need smaller cheques and patient capital.

To diversify the kinds of risk capital available to Australian innovators, we must start to dismantle the

barriers that prevent talented individuals from launching smaller funds with diverse mandates. The prohibitive economics of sub-$20 million funds, the catch-22 of needing institutional capital to attract institutional capital, and the severe personal consequences of failure all conspire to keep promising fund managers on the sidelines.

The solutions are neither complex nor prohibitively expensive. Adjusting the superannuation performance testing regime could unlock up to $50 billion in patient capital for venture investment; lowering the ESVCLP threshold would level the playing field for emerging managers; expanding programs like LaunchVic’s successful VC Support Program nationally could provide the on-ramp that talented individuals need to establish credible fund operations. In time, a VC fund-of-funds could create a structured pathway for high-potential fund managers to become ‘institutional-grade’ and access larger amounts of capital as they scale.

The stakes extend beyond venture capital. In an economy struggling with productivity growth and falling complexity rankings, we need entrepreneurial dynamism across all sectors; we need fund managers willing to back the diverse businesses that drive broad-based economic growth.

The health of Australian entrepreneurship depends not just on minting more software unicorns, but on cultivating an ecosystem where different types of fledgling businesses can access appropriate risk capital.

Disclaimer: The author was formerly a partner at an early-stage venture capital fund and currently runs a communications agency focused on the technology sector. Her agency has provided services to several emerging fund managers, including Ecotone Partners and Advance VC, who are mentioned in this article.

Jessy Wu is the Founder and Managing Director of Encour. She was previously a partner at AfterWork Ventures.

A unicorn is a startup company with a valuation exceeding $1 billion.