Best practice for supply-side reform

To maximise the impact of supply-side policy, reform should focus on bans over burdens, and markets over individual firms.

This essay appeared in edition three of Inflection Points.

We’re thrilled to see Katie Roberts-Hull‘s essay included on Grattan Institute‘s 2025 Wonks’ List. You can give her essay a read in edition one.

By Matthew Maltman

In 2007, Steven Levitt of Freakonomics fame1 posed a question to his readers: why had the amount of shrimp consumed per person in the US nearly tripled over the prior three decades?

He wasn’t interested in seafood; instead, he wanted to test a theory: that economists are trained to think about the world in terms of supply, while others (normal people) think in terms of demand. After all, we spend most of our lives as consumers, not producers, so it’s natural our default explanations empathise with that side of the equation.

The results of Levitt’s (highly unscientific) survey partially confirmed the theory: most normal people did indeed largely conjure up demand-side explanations—we’re eating more shrimp because we’ve become more health-conscious, they thought, or because seafood advertising has become more persuasive. Few thought of supply-side factors, like improved aquaculture technology. In fact, the demand-side bias was so strong even economists responded with mainly demand-side reasoning.2

This asymmetry of intuition isn’t a problem in everyday conversation—the average punter doesn’t need to accurately explain economic shifts. But in public policy, that bias can matter. If, for example, our economic challenges stem evenly from supply and demand, we’ll be pre-disposed to misdiagnose half our problems, and quickly be left with policy problems that we can’t fix using our basic mental shortcuts.

This framing for public policy failures is crude, and it’s wrong in plenty of cases, but it does fit in others. People are generally quick to grasp that migration adds to the demand for goods and services, but slower to recognise that they expand supply too. People are good at understanding lower demand will reduce prices, but less so that an increase in supply can do the same.

The supply-side of the economy, it seems, has a PR problem. Perhaps this is because talking about “supply-side economics” conjures images of Reagan and Thatcher, of “neoliberalism”, of “trickle-down economics”, of regulatory cuts for large firms, or tax-cuts for the wealthy. Or perhaps it’s because some commentators muddy our conversations with strange views that supply doesn’t affect prices, or that output is somehow predetermined by coordination among firms.

But I think our problem is deeper than this. I think we struggle in general to tell supply-side stories. People can’t articulate what supply-side reform even looks like, let alone how it could benefit them. Often this is because the supply-side involves niche or nebulous topics that you don’t encounter in the day-to-day—planning codes, electricity grids, and quasi-markets. And when supply-side interventions work, their benefits are quiet—diffuse, incremental, and slow.

A good reform might shave a few dollars off your cost of living or slightly improve the quality of what you buy. And while everyone sees a demand-side subsidy; no one sees the price that, thanks to greater supply, never rose in the first place. I can comfortably say that Australia’s income contingent university loan (HECS-HELP) program has made my life materially better by taking the stress out of university loans. But I struggle to quickly think of a comparable policy on the supply-side which had an impact of the same magnitude to me.3

What we talk about when we talk about supply

Australia, like many advanced economies, is now grappling with how to restart its supply-side engine. And a big part of that is restarting a conversation on the side of the economy most of us really struggle to talk about. For two decades, we’ve had little in the way of genuine microeconomic reform. The reasons for that have been well covered, but at least there’s now recognition that it needs to change—that we can’t meet our biggest challenges solely by subsidising more or regulating harder.

We need to make and do more, and precisely in the parts of the economy where we have found it hardest. We need to build vastly more housing to lower rents, vastly more clean energy to decarbonise while keeping power bills low, and vastly more aged and childcare capacity to support an ageing population.

This doesn’t mean supply-side reforms always work, or that they’re costless, or distribution-neutral. But it does mean we need to get better at identifying which ones matter, and at explaining why they’ll improve people’s lives.4 For that, I think a good place to start is an example of recent success.

In August, I published a working paper arguing that a series of zoning reforms in New Zealand during the 2010s—which legalised medium-density housing across several cities—lifted productivity in residential construction. Over that decade, New Zealand, and Auckland in particular, built more homes than ever before without even close to a proportional rise in labour.

These reforms have been written about widely already, usually in terms of housing affordability. While that framing is true and important, I’m increasingly convinced it also undersells the impact. These were classic microeconomic, supply-side reforms in the spirit of what Australia did in the 1990s: they allowed more to be produced with proportionally fewer inputs; reduced costs for consumers; expanded the market for producers; and drove economic growth. In fact, neither of the two leading New Zealand housing reforms were motivated by housing affordability directly—both were about growth and productivity.5 We should talk about them in these terms.

So, while the question “did zoning reform lift construction productivity in New Zealand?” is in some respects a narrow one, I think there are stories we can pull out from these reforms to change the way we think.6 In particular, I think they offer three ideas we should keep front of mind in our policy conversations:

First, we need to be guided by evidence on impact, not ease. We far too often reach for supply-side reforms that are politically easy but economically small. Usually this means press releases about getting government working faster, making paperwork shorter, and speeding up approvals. Worthy goals sure, but the evidence suggests that they don’t massively shift the dial. The real barriers are the rules that prohibit activity altogether. It’s the regulations themselves, not how they’re administered.

Second, reform is about markets, not firms. We too often think the supply side of the economy is just the sum of all firms within it. So, we go ask industry what it needs to grow. But good reform means creative destruction: some old firms die, and some new firms enter. Often the biggest beneficiaries are those who do not yet exist.

Third, the job of policy is to get the inputs right; the outputs will follow. Real reform is about controlling the controllables — the upstream settings that quietly shape outcomes, even if they seem abstract to voters or lack immediate political reward. Getting those settings right rarely delivers instant results; sometimes all it does is stop the bad from getting worse. Prices at the check-out reflect what happened on the trawler, the bid at the auction what happened at the planning meeting. Those points may feel distant from public debate, but by the time you’re downstream, it’s too late to change the current. The patient work of getting the settings right is what makes steady progress possible, even if it doesn’t happen tomorrow.

If we want real microeconomic reform, we need to tell better stories about it— ideally set in this century, not the last one. Too often we talk about the 1990s as if reform was easy then because the fruit was low-hanging and the consensus was clear. We need new heroes. New Zealand’s housing reforms show that expanding the pie is still possible: they got more goods for less, and lowered prices along the way. The reason this story is told again and again in housing circles is not just that it’s extremely well-researched, but that it’s totemic. It teaches us to think about supply. It helps us understand the real reasons why we’re eating more shrimp.

Part I: This is your city on supply-side reform

In the early 2000s, Harvard economist Ed Glaeser posed a simple question:7 how can home building—a highly competitive industry with almost no natural barriers to entry—coexist with housing prices far above costs?

The answer was equally simple: zoning regulations.

By restricting the ability to build denser housing in desirable areas, planning rules drive a wedge between supply costs and market prices. Over several decades of work, Glaeser assembled an impressive evidence base showing that these restrictions resulted in high housing prices in major U.S. cities. The policy implication was clear: to make housing affordable, loosen the rules that stop it from being built.

Economists read the research with fascination. Western governments, for the most part, ignored it.

****

In 2010,8 the New Zealand Government forcibly amalgamated eight Auckland councils into one single Auckland Council and directed it to produce a unified land-use framework. That process led to the Auckland Unitary Plan (AUP)—drafted in 2013 and made operative in 2016—which replaced a patchwork of legacy zoning rules with a consistent, region-wide system aimed at enabling more housing close to jobs and transport.

The AUP’s main innovation was its large-scale upzoning of suburban land. Where most of Auckland had previously been restricted to detached single-family dwellings, around three-quarters of its residential areas were rezoned to allow townhouses, duplexes, and small apartment blocks, with greater height and density permitted along transport corridors.

A more recent reform occurred in Lower Hutt, a major city of around 100,000 people in the Wellington region. In 2017 the council implemented Plan Change 43, a policy which enabled more medium- and high-density housing. In 2020, Lower Hutt became the first New Zealand city to fully remove minimum parking requirements and more recently introduced a new high-density zone allowing up to six-storey buildings across much of the city’s flat urban land. Collectively, these reforms represent a staged but ambitious upzoning program that substantially expanded development capacity across the city.9

Zoning reform led to undeniable increases in supply

In 2013—the year the AUP was first partially enacted—Glaeser found himself on a lecture tour in New Zealand. His lectures, which drew hundreds, were described by attendees as “revelationary” and left a lasting imprint on New Zealand’s emerging urban economics and policy community.

His ideas were about to get its first large-scale test: Auckland was going to be the first city in the world to meaningfully relax zoning regulations.

****

I’m largely an applied microeconomist. To caricature my field for a moment, our usual approach goes like this: identify a policy challenge, find a clever counterfactual, measure the difference between what actually happened and what would have happened otherwise—and there’s your policy effect.

At my current job, one thing I’ve learned is that if you want to do applied microeconomics effectively, you should first “show it in the raw data”. In other words, the most convincing thing you can do is to show the audience the simplest presentation of events possible. Sure, you should still do your complex statistics, generate your brilliant counterfactual—but first just show the raw numbers. If you can see an effect there, you’ll find it easier to convince people you’re not hiding anything in the statistics.

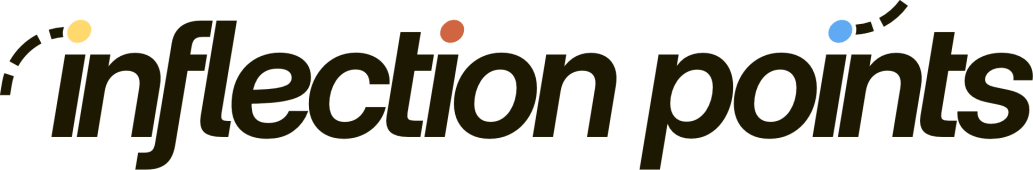

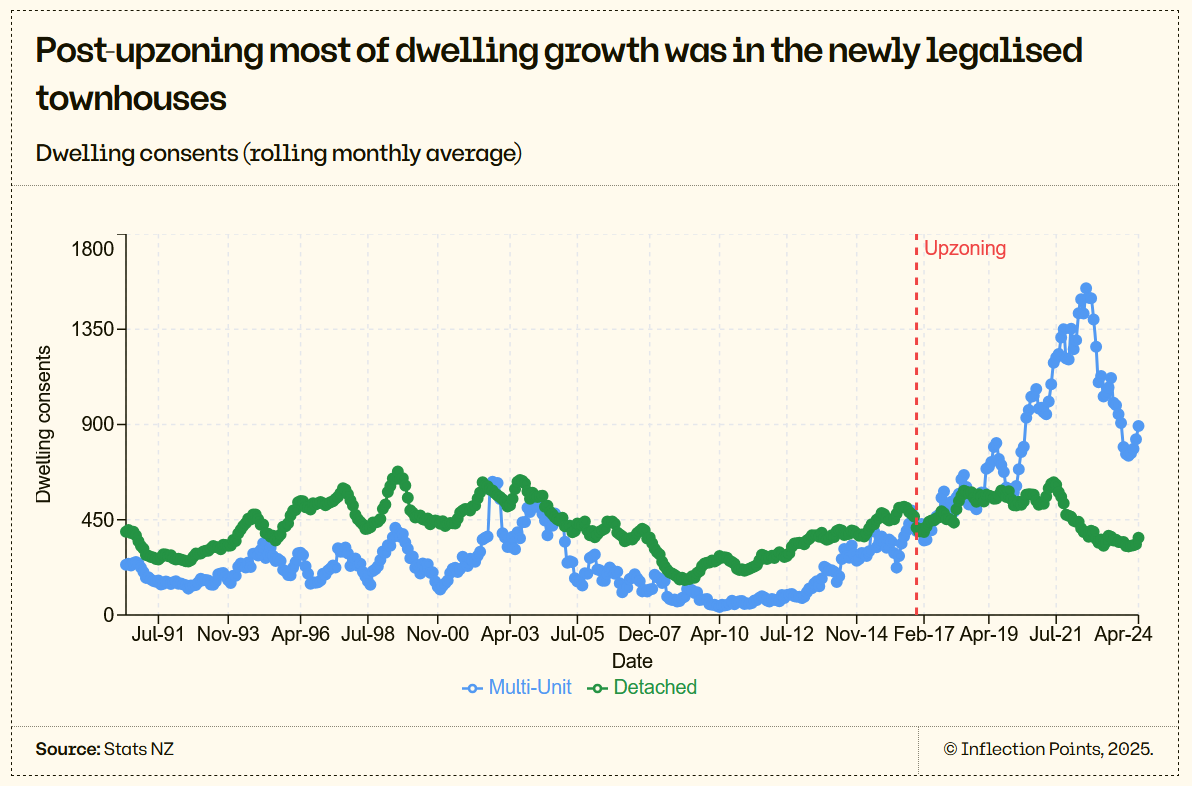

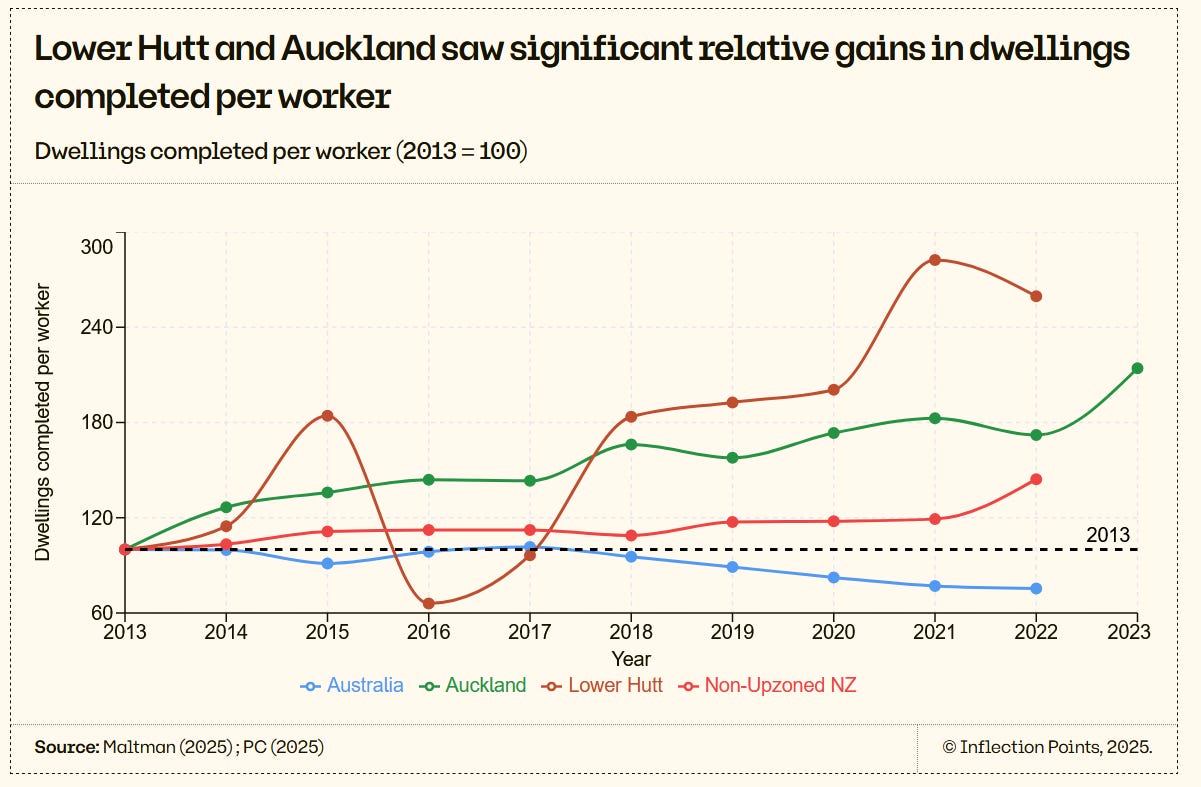

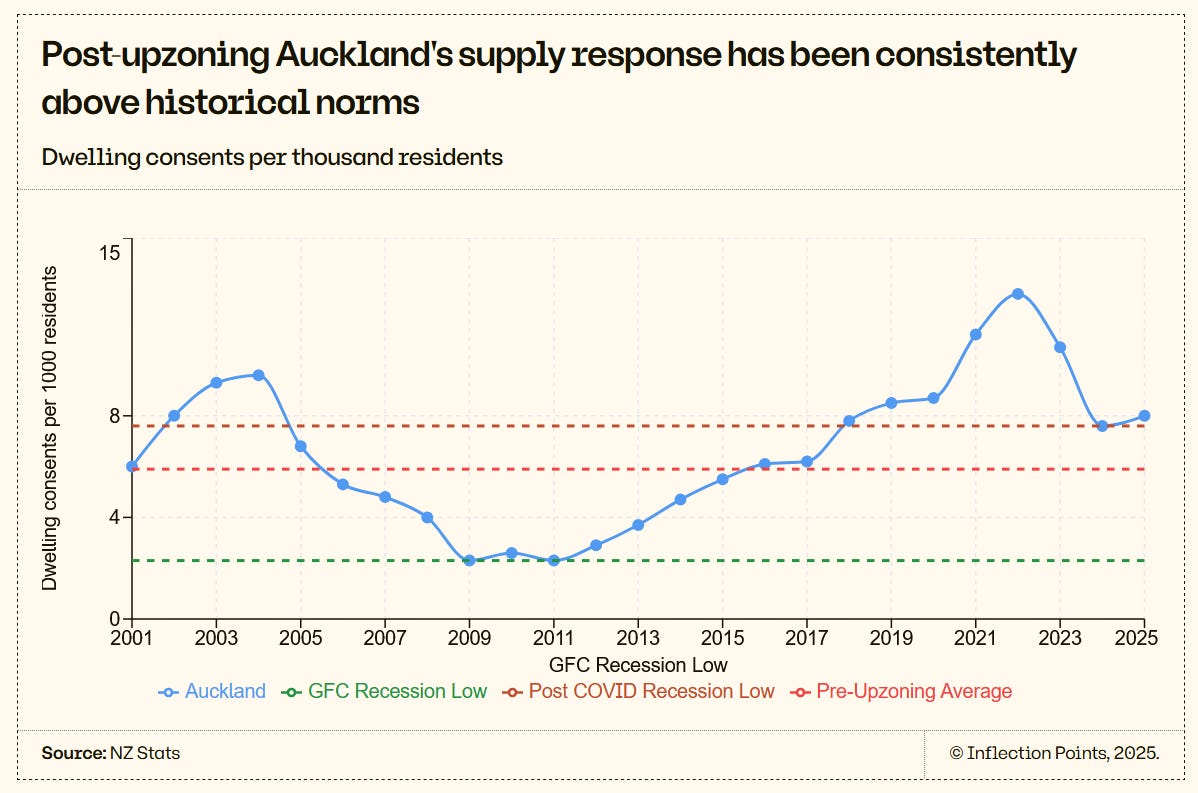

Luckily, the impacts of zoning reform are so large that they make adhering to this principle easy. In a simple time series, Auckland went from on average matching national construction rates prior to 2016, to smashing them in every subsequent year. By 2022, Auckland’s per-capita housing construction rate had surged to 30 per cent above its previous record, where population growth was negative, and while the rest of New Zealand barely moved.10 Almost all the new dwellings were townhouses built in the very areas newly legalised by the reform.

Lower Hutt’s effect is even more obvious. The city had never built more than 2.5 dwellings per 1,000 residents in a year prior to their reforms.11 They built 12.2 per 1,000 residents in 2022. Once again, nearly all the new homes were townhouses built in areas newly zoned for them.

Although you can see these supply effects simply in the raw data, it’s also worth confirming using our more sophisticated economic methods. Three studies show large supply effects in both Auckland and Lower Hutt: half of the new supply or more was directly due to the reforms.

There’s always a risk of a false positive. So these studies try to push the data as hard as possible to try to make the effect go away: they ask, for instance, what if we only compare these to cities with strong population growth? Or to Australian cities? What if we change the date we expect to see a policy effect? What if we account for spillovers? Nothing even comes close—the effect is too strong.

Consumers feel the affordability dividend of new supply

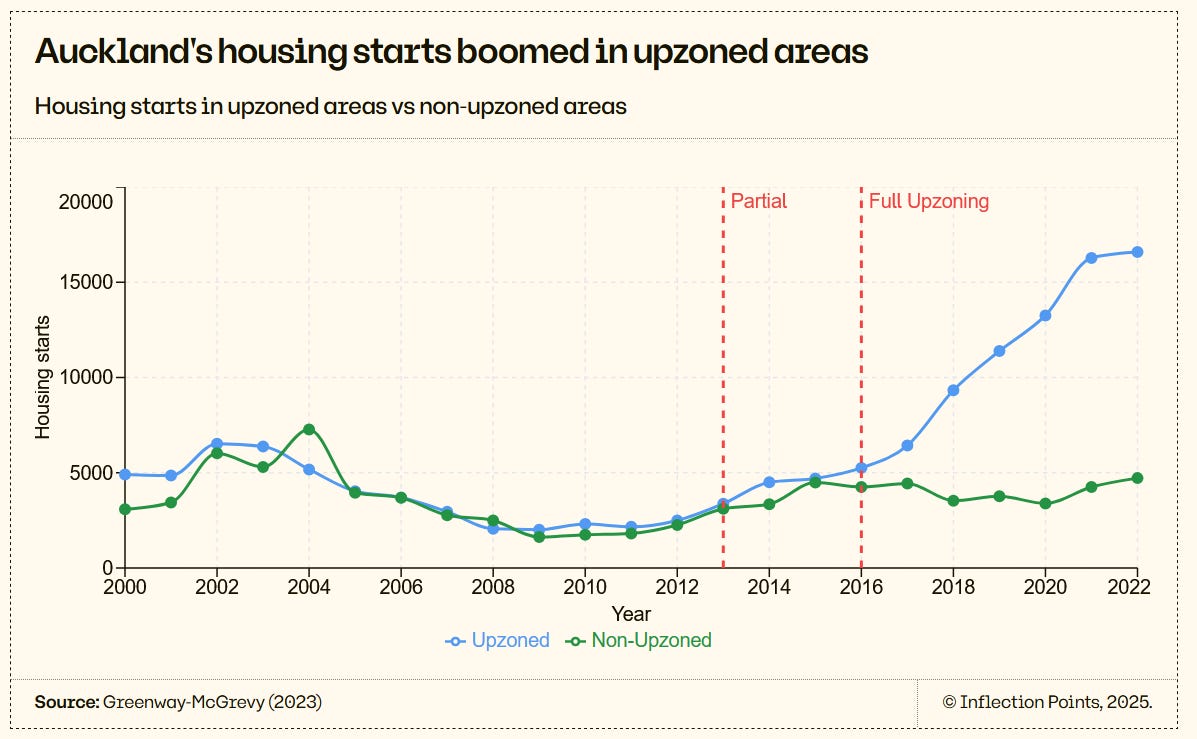

Before zoning reform, Auckland’s rents had been rising faster than elsewhere in the country; within a few years they were rising more slowly, and then not at all. In 2020, for the first time on record, Auckland became more affordable to rent in than the rest of New Zealand—a gap that has continued to widen since.12

Again, more sophisticated analysis suggests rents are over 20 per cent lower than they would otherwise have been. Median house prices have fallen in Auckland since the AUP, while they’re up 30% in the rest of New Zealand. And if you’re concerned about the distributional consequences of this, rents for the bottom quartile of renters have fallen by more than higher up in the market. State-Developed Housing (New Zealand’s equivalent of social housing) also tripled after reform; the mechanism is obvious—make social housing cheaper to build, and you can build more of it with a given funding envelope.

And, while rents in comparable small cities surged during the post-pandemic housing boom, rents in Lower Hutt rose by much less. Over the four years from 2022, rental affordability deteriorated by around 1 per cent nationally—but remained unchanged in Lower Hutt.

The reward for reform is this affordability dividend — the quiet but profound gains that show up in people’s lives. It means a young couple buying their first home years earlier than they thought possible. It means a child getting their own bedroom instead of sharing. It means a university student able to move out, take on more independence, and build a life of their own. These are the stories that make the abstract language of supply and reform real — the downstream proof that getting the inputs right changes what’s possible for ordinary people.

Construction productivity can be unlocked by loosening supply restrictions

The construction sector is a global productivity puzzle. Around the world, while we have gotten better at making all kinds of stuff—like cars, phones, pharmaceuticals—we haven’t gotten better at building houses. Indeed, as Glaeser and others have shown, the productivity of a construction worker in the U.S. has remained unchanged since the 1960s. It’s a similar story for Australia.

This productivity divergence mirrors a diverge in price: houses have become more expensive over time, while cars and other goods have gotten cheaper. The improved quality of houses don’t explain these trends, nor do the techniques we use to measure construction output.

But this is a global phenomenon. The entire Anglosphere has seen flat or falling construction productivity over the past two decades.

There’s one exception.

****

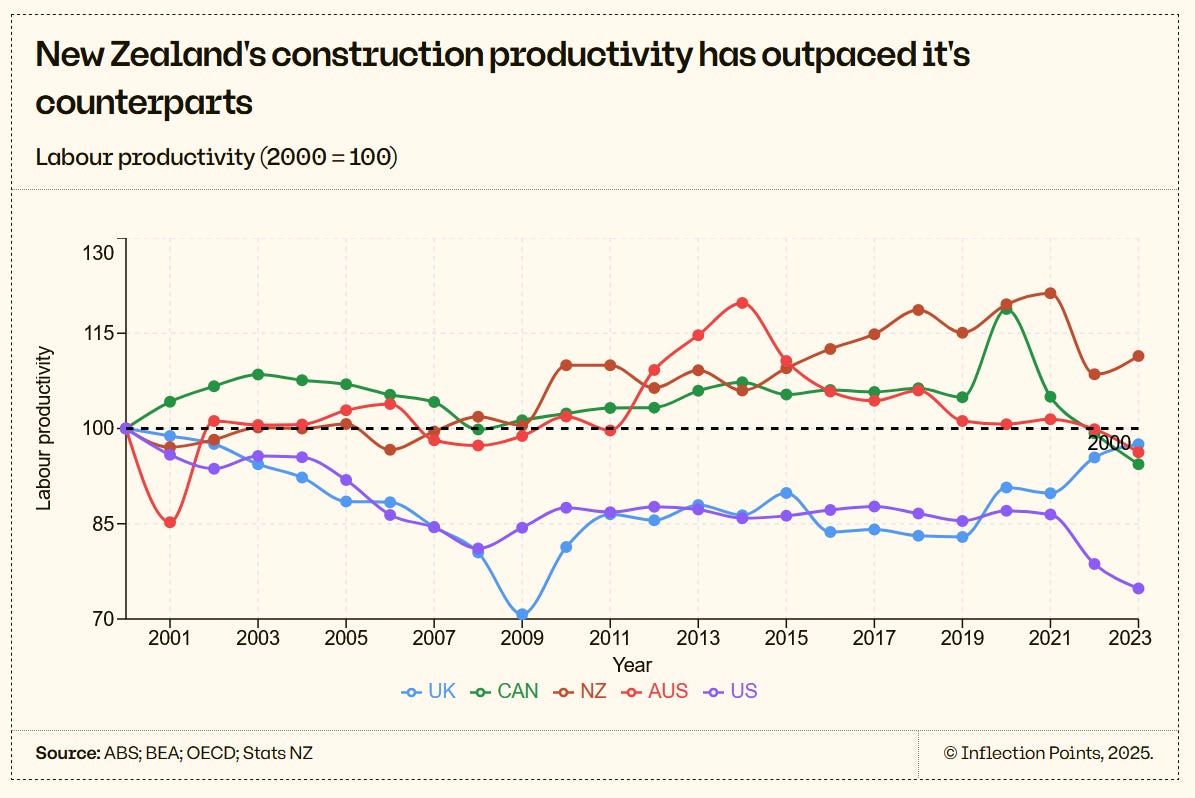

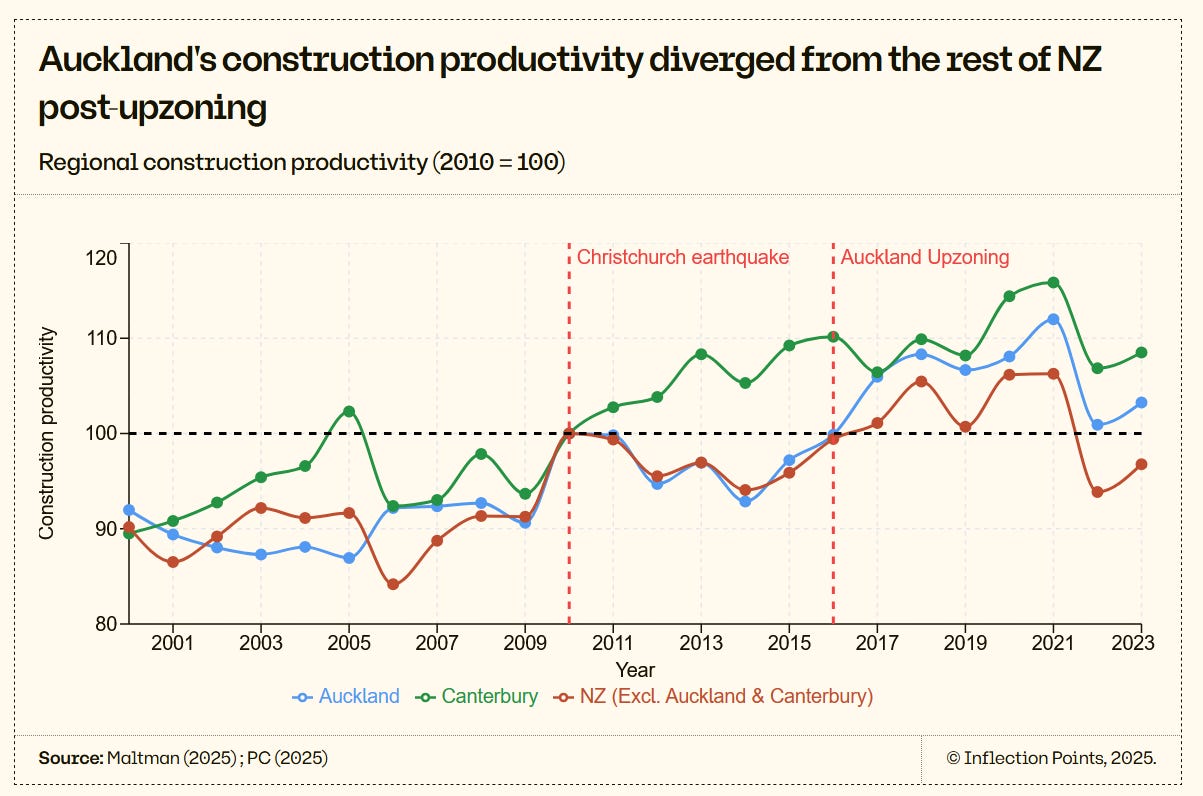

As much as Australians like to kick ourselves for our stagnating productivity, the slowdown has been a largely global phenomenon. It’s hard to imagine one country staying ahead of others for long in industries where materials, labour, and new ideas are shared easily across borders.13 This holds in construction. On the chart below of the Anglosphere’s construction productivity since 2000, you could easily switch the labels between Australia, New Zealand, and Canada and not lose any meaningful information—until 2013.

That’s when something weird happens. Australia and Canada begin to fall,14 and New Zealand begins to climb.15 That’s kind of strange. If construction sector productivity stagnation is a global, secular trend, how could this divergence occur?

The timing fits almost exactly with the implementation of zoning reform in Auckland. And when you dig further, more and more pieces of evidence emerge that zoning changes contributed to this rise.

First, the effects were indeed concentrated in areas which adopted zoning reform. In 2013, Auckland completed 0.16 dwellings per worker. In 2023, Auckland completed 0.34—a more than doubling. Lower Hutt saw a greater rise. The rest of the country saw a 44 percent increase (or 19 percent if we exclude the pandemic recovery year of 2022). According to CEDA, for Australia this ratio was 0.14 in 2013, and 0.14 in 2022.16

Second, these changes don’t just reflect building smaller houses. Floor space per worker also rebounded in the upzoned regions, rising from around 25 square metres per worker per year to nearly 40 in Auckland after the policy change, while remaining effectively unchanged in comparable regions.

And third, the productivity boom was concentrated in areas related to residential construction: output per worker in building construction rose by more than 20 percent over the 2010s, and in construction services by about 15 percent—while productivity in infrastructure construction actually fell.

Taken together, these facts make a coherent story. While we may never be able to run a perfect counterfactual for productivity, the evidence points in one direction: where planning rules allowed supply to respond to demand, productivity followed.

The what, how, and where of construction productivity

It seems that productivity went up due to these changes, but why? The answers perhaps lie in greater choice for firms in what they could build, increased market dynamism, and supply centralisation.

First, the reforms changed what could be built. By expanding the types of dwellings allowed, zoning reform dramatically widened the choice set for developers. Instead of being locked into detached, single-family homes, firms could now build medium-density housing—townhouses and apartments—across most of Auckland and in parts of Lower Hutt. This shift matters because:

Even if the total floor space built stayed the same, more dwellings could be produced with the same number of workers. The data show exactly that.

There may be genuine productivity gains in floorspace per worker as well. Medium density construction may lend itself to economies of scale. While we need more data to properly unpack this, one explanation is that builders can spread fixed costs—for instance land preparation- over a greater amount of floor space because more was completed in a common location.

Second, zoning reform changed how the construction market operated. The e61 Institute has documented that productivity growth is closely tied to dynamism: how many new firms enter a market and the competition that this fosters. The theory goes that productivity growth is in part driven by creative destruction: new firms and ideas oust and challenge old ones. And that’s what we saw in New Zealand after zoning changes.

Firm entry went up dramatically in areas with zoning changes, and the medium density housing market appears to be meaningfully more competitive than the detached housing market. This likely reflects the way reform lowered barriers to entry: projects required less land and hence less on the balance sheet at any point in time, reducing the upfront costs of participation. Those changes opened space for smaller firms to compete, brought new entrants into the market, and increased the churn that drives productivity growth.

Firms also got larger, on average. The average residential construction firm in Auckland grew by nearly 60 per cent in size between 2013 and 2023, with similar expansions in Canterbury and Lower Hutt after their zoning changes. Most of this came from small firms hiring their first employees or modestly increasing headcount, with the share of one-person firms declining. There was no change in firm size in non-residential construction, nor manufacturing, nor the economy at large. The theory is that larger firms can capture economies of scale, invest in technology, and specialise—all classic channels of productivity growth.

Third, upzoning shifted where construction happened. As more activity concentrated in Auckland and Canterbury—the two most productive, and largest, construction regions in the country—aggregate productivity rose mechanically. Workers in these cities produced roughly $75,000 NZD ($2010) of output per year, compared with around $65,000 elsewhere. This benefit is itself due to their size and density, with agglomeration benefits of their scale and specialisation leading to lower costs of supply.

On all counts, it seems that as microeconomic reform goes, these zoning changes in New Zealand were a major success: they got more output, lowered costs to consumers, created new opportunities for firms, and seemingly had a positive impact on productivity.17 So why isn’t Australia following?

Part II: The anatomy of good supply-side reform

In Woollahra Council in Sydney, a development application submitted in 2024 took around 184 days on average to be approved. But there’s a simple trick to speed up the response from the council: ensure the development application contained a request to subdivide the property into a duplex. Chances are you’d hear back quickly: with a no, because duplexing is banned in Woollahra.ollahra.

****

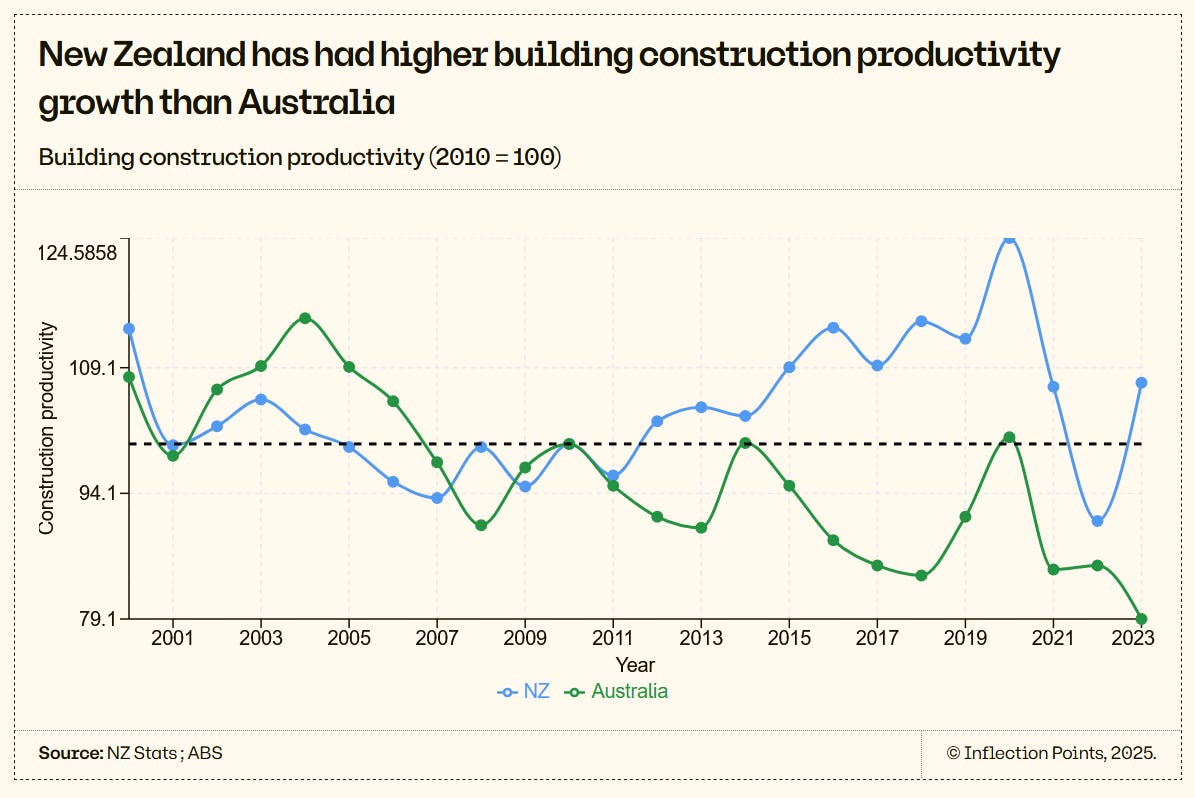

New Zealand and Australia are intertwined in all sorts of ways. There’s a provision in our constitution which allows them to become a State, if they ever so wish. We poach loads of their great economists. Our statistical agencies, helpfully, use the same definitions for industry codes. And, each year, we go through the humiliation ritual that is playing them in rugby union for the Bledisloe Cup.18

This allows us to make a like-for-like comparison on building construction productivity between the two nations. The result might as well be as bad as the Bledisloe.

This isn’t due to a difference in caring—Australia has had several reviews of our National Construction Code over the past 20 years, we’ve had a Productivity Commission review into the construction sector, and we’ve seen dozens of serious articles written on the topic. Nor is it the case that New Zealand has outperformed Australia in general productivity terms—our productivity growth rate has been higher than theirs in most sectors.

But they’ve done something that has worked, and we haven’t. This is a case where we shouldn’t just be peeking over at their answers, we should be taking notes and implementing.

I think there are three lessons from New Zealand’s supply-side housing reforms that can be generalised to broader supply-side efforts. First, they targeted regulatory bans rather than regulatory burdens. Second, they focused on markets rather than firms. And third, they got the policy inputs right—even if the outputs didn’t immediately follow.

Target Bans, not burdens

In 2012, Lower Hutt, facing a shrinking population, set out to jump-start housing construction. Its first move was a “Development Stimulus Package,” waiving building consent fees and development contributions. It was a classic policy aimed to reduce the burden on firms: lower the cost of engaging with government and undertaking business, and hope builders respond.

They didn’t—at least not much. Over the next six years to 2018, just 188 new dwellings used the scheme.

Then, in late 2017, the city tried something different: a broad scale upzoning that allowed for medium density construction across most of the city. The effect was dramatic. Over the next six years, 4,867 dwellings were consented: 3,006 of them likely directly due to the zoning changes.

For the six months the two policies overlapped, 106 dwellings qualified under both, around 56% of the previous six years of Development Stimulus package.19 The problem? Too much was being built: the stimulus scheme was costing too much in foregone revenue. The council had to scrap it.

Four years later in 2021 Lower Hutt raised, not cut, development contributions to fund new infrastructure. Developers protested that the policy change would increase the cost of housing. They complained that the city’s processes were too “open-ended” and that engaging with government was too costly. The following year, Lower Hutt approved the most dwellings on record: six times their average pre-upzoning year.

****

Broadly speaking—and at the risk of massively over-generalising—I think bad regulatory settings come in two forms: burdens and bans.

Burdens are instances where governments still allow things to happen, but make them slower, costlier, or more cumbersome. They require firms to spend more time, hire more compliance staff, or incur new costs due to government processes. Long wait times for permits, complex documentation, and heavy reporting requirements all fall into this category — whether it’s for a new health tech startup, a solar farm, or a housing development.

Bans, by contrast, are rules that literally prevent things from happening—or make outcomes so uncertain that firms face a real probability that a project never proceeds. These include zoning and land-use rules that restrict what can be built, as well as occupational licensing, quotas and caps that limit output, and merger controls. Even the government’s recent reforms to restrict the use of non-compete clauses belong here—paradoxically an instance where more regulation allowed more economic activity to happen, because the prior unregulated labour market was preventing workers from switching jobs at the same rate.

Another way to think about the distinction is through the margins of adjustment. Burdens operate on the intensive margin, or how much of something happens: activity can still occur, but the costs mean you probably get less of it. Bans operate on the extensive margin, or whether something happens at all: they stop activity altogether—the house or wind farm can’t be built, the worker can’t move, the firm can’t start.

Throughout the 2010s, much of the housing supply-side debate focused on burdens rather than bans.20 The shift in emphasis came only later, largely through the work of Peter Tulip at the Reserve Bank of Australia.

Tulip’s point was simple but powerful. When economists try to quantify the costs of regulatory burden in housing, they usually find modest effects—in the order of a few thousand dollars per dwelling, or around two per cent of total construction costs. But the evidence on bans tells a different story. Tulip’s work, alongside a series of international studies, shows that the economic cost of the zoning restrictions themselves is orders of magnitude larger—often well above 20 per cent of dwelling prices, or hundreds of thousands of dollars per home. Supporting analysis from New Zealand likewise finds that the benefits of zoning reform outweigh the costs roughly two-to-one, delivering thousands of dollars in welfare gains to households over coming decades.

Put plainly, reforms that lead government to say ‘yes’ more often are far more valuable than reforms that merely make it say ‘no’ faster or more clearly.

Empirical evidence reinforces this. At least five credible studies now find that jurisdictions adopting zoning reform experienced large, measurable increases in housing supply—in some cases, doubling the rate of new construction. By contrast, there are no studies showing that speeding up approvals, shortening planning documents, or reducing engagement costs produces results even in the same ballpark.

That bans appear to matter more than burdens isn’t an absolutist claim—it’s simply where the weight of the evidence currently lies. New research could well shift that view, but it would need to be persuasive to overturn what we have seen so far.

Still, it’s worth asking why this evidence gap exists. If approval times, documentation complexity, or development charges are truly the main constraints on supply, why don’t we have strong empirical evidence quantifying their effects? If longer building codes meaningfully slow productivity, or if faster local approvals materially increase output, these are important things to know—and valuable areas for further research.Either we are under-producing credible research on the effects of burden-reducing reforms, or we are massively overweighting our policy conversation towards these topics.

Empirics aside, there are also good theoretical reasons why these two kinds of reform differ. Burdens may deter entry by raising fixed costs, which is bad for competition and dynamism—but in some circumstances, they might even raise productivity if they keep out the least efficient potential entrants. Highly productive firms often find ways to enter and expand despite bureaucratic friction, because their business models remain viable even when government is slow or cumbersome.

Bans are different. They prevent activity altogether. When they bind, they block profitable, welfare-enhancing projects or ideas from ever occurring. In housing, that means it is highly profitable and socially valuable to build medium-density homes—but it simply isn’t allowed. In green energy, it means the most efficient sites for renewables can’t be used. In care services, it means a provider can’t adopt a new delivery model.

Of course, not every ban should be lifted, and not every regulation is harmful. Many burdens are simply the necessary functions of good government—ensuring quality, protecting consumers, and managing risk. Getting approval times down isn’t linearly good for productivity – at some point you start cutting important regulatory processes that help, rather than hurt, society.

And, none of this means we shouldn’t shorten the National Construction Code, or speed up council approvals, or make public systems easier to navigate. Productivity is a game of inches. But as my good friend Zachariah Hayward likes to say: governments can do anything, but not everything. Reform costs political capital: airtime, column inches, and votes. You don’t win the Bledisloe from inches. Occasionally, you need to make a big play.

Think about markets, not firms

When Auckland undertook its major zoning reform in 2016, the number of construction firms rose markedly. Firm entry rates, which had tracked the national average beforehand, jumped around five percentage points and stayed there for a decade. Today there are 4,245 more housing construction firms in Auckland than when the AUP was fully enacted.

None of these firms were consulted before the reform. They did not attend roundtables, submit to inquiries, or appear in stakeholder surveys. They couldn’t have, because they didn’t exist.

****

Given the evidence that bans matter far more for productivity and output than burdens, why does our reform debate always drift back to “cutting red tape” and “speeding up approvals”? The answer lies in the political economy.

Reforms that target regulatory burden mainly impose costs on government itself—demanding more from the public service but creating no clear losers outside it. These reforms are politically comfortable—nobody likes bureaucracy except for those that are within it. “Wait, you’re telling me you can get my government to work faster, with no trade off? And the rest of us don’t have to do anything, or make any tough choices? Sign me up.”

Ban reforms, by contrast, are structural: they change who can do what, where, and with what consequences. This creates winners and losers. Tariff reform in the 80s and 90s, for instance, helped consumers and importers but hurt manufacturers. Speeding up customs procedures or foreign investment approvals would make little difference if the underlying restrictions meant approval was always destined to be “no.” It’s the removal of the ban, not the efficiency of the bureaucracy, that changes outcomes.

The same logic applies to zoning reform: lifting bans on medium-density housing expands opportunity for some builders, but threatens established interests, shifts land values and neighbourhoods, and disrupts business models. In post-upzoned Lower Hutt, firms specialising in detached homes were often entirely different players from those in the new medium-density market. It’s not clear that the existing firms benefitted from reform; to the extent that they did benefit, they had to alter their focus.

The problem is that when governments turn to “supply-side reform,” their first instinct is to consult industry—the firms already in the market. This makes sense as a first pass to get a lay of the land: speak to those who live and breathe the sector every day. But it will never be sufficient to understand the whole market.

In the Productivity Commission’s inquiry into construction productivity, for instance, stakeholders consistently pointed to slow processes and regulatory complexity. No one in industry identified zoning reform as a lever for productivity.21 NAB’s developer surveys tell the same story: construction costs and permitting delays dominate the reasons holding back new housing projects. Zoning regulations themselves aren’t even an option on the survey; the closest is “lack of development sites”, which ranks only fifth of eight. If you asked a typical Australian property developer whether allowing medium-density housing across most of Sydney would be good or bad for their business, I have no idea what they would say. This is a large divergence from the academic consensus that zoning reform is the most powerful tool to increase housing supply.

This divergence comes from the fallacy in the policymaking process that the “supply-side” of an industry is just the sum of firms currently there. This belies that incumbents, by definition, are the ones who’ve managed to succeed under the current system, and so it’s unclear how much they want it to change structurally. Nor is it even clear they have the time, resources, or incentives, to imagine what structural change could look like. They’re trying to score more points under the current rulebook—they’re not interested in rewriting the rules to make the game play better.

The supply curve—what matters for reform—is all the output that could be produced by anyone. The goal of policy is to shift that curve outward. Whether that happens through existing firms scaling up or new firms entering should be irrelevant. The market determines how many goods and services are produced, not firms.

If policymakers rely solely on the perspective of industry, they will consistently under-estimate the benefits of structural reform. The firms who can best describe the potential gains from liberalisation are those who would enter or scale up after it occurs and, by definition, have no voice in the policymaking process under the status quo.22

Control the inputs, monitor the outputs

IIn 2005, Auckland tightened its minimum apartment-size rules. The New Zealand Infrastructure Commission later estimated that these changes meaningfully reduced the city’s zoned capacity. Apartment construction—which had been rising steadily—began to fall, dragging down overall housing supply.

Three years later, in March 2008, the global financial crisis hit, sending New Zealand into a 6-quarter recession. The economic downturn crushed housing supply in Auckland, which dropped to the lowest level on record: 2.3 per thousand residents, less than half its long-run average. The affordability gains of the 2000s quickly reversed as rent-to-income ratios rose by two percentage points.

Fast-forward fifteen years. Between 2022 and 2024, New Zealand again experienced six quarters of negative growth—three technical recessions: one in each year. The construction sector was hit especially hard as the cost of materials surged by 30%. Housing supply in Auckland fell sharply once again.

But this downturn was different. Construction dropped from 12.8 dwellings per 1,000 residents in 2022 to 10.7 in 2023 and 7.6 in 2024, before rebounding. Some commentators described it as “construction crashing”. Yet activity never fell below its pre-upzoning average. In fact, Auckland’s worst year since 2018 would still have ranked as its fourth-best year in the seventeen preceding it. Commentators are now in awe at Auckland’s house-price decline—the product of years of accumulated supply.

****

When economists recall the “golden age” of productivity reform—the 1980s and 1990s—they point to the microeconomic breakthroughs: tariff reductions, a floating dollar, financial deregulation. Yet even at their most ambitious, these reforms explain only a fraction of overall growth. The rest came from innovation, technological diffusion, and the creative activity of the market.23

That remains true today: governments can shape incentives and remove barriers, but global shocks, financial crises, wars, and pandemics can still derail the best-laid designs.

This makes it hard to define what “success” looks like for government. Demand-side policy lends itself to clear metrics: greater subsidies and lower prices for consumers, more places, greater access. Supply-side policy doesn’t work that way. Governments can’t declare the outcomes they want—they can only influence the conditions under which better outcomes become possible. Because of that, it’s difficult to know whether governments are doing “enough”.

Over the past decade, we’ve cycled through debates that try to measure success in unhelpful ways. During the 2010s, for instance, researchers obsessed over quantifying Australia’s “housing shortage”—an effort to put a number on whether we were overbuilding or underbuilding. Do we even need more? If so, how much? Despite using similar data, some found a massive undersupply; others, a surplus.

The divergence wasn’t about the data, it was about the economics.24 In a market without price controls, textbook “shortages” can’t persist — prices simply rise until demand and supply meet, albeit at worse living standards. It’s not about whether the number of houses is “right”, but whether Australians are living worse than they should be — crammed into smaller homes, staying longer with parents, or pushed further from work.

That’s why the question “how many homes should we build?” is the wrong one; it’s essentially meaningless. We don’t ask how many cars or iPhones Australia “needs.” There’s no department forecasting the ideal number of cafes in the CBD. The right questions are: Are there policies that would let us build more? And would Australia be better off if we did? On zoning, the answer to both is a resounding yes. To some extent, it doesn’t matter whether we’re already producing a little or a lot—the question for government is always the same: could things be better? Microeconomic reform, at its core, is the discipline of marginal improvement.

We’re now having the same conversation again, this time around the government’s ambition to build 1.2 million homes in five years. Some critics treat the target as unachievable—arguing that market cycles are dominating so the governments are powerless to hit it. There’s a kernel of truth in that: the number of homes built will fluctuate with costs, interest rates, and labour availability. But it’s the wrong way to think about what a target is for. Done right, it’s an expression of values—a statement of intent about the kind of economy we want.

I think at their best, targets are signposts, not scoreboards. They say we want things to be better than they were in the past, and that we want that to be the case soon. But that means you have to be willing to do the hard yards to make things work.

Think of government like a coach. You don’t control the scoreline, but you do control the squad, the tactics, the conditioning, the preparation. Luck and external factors matter — and they mean you’ll lose a few, in the short run. But over time, good systems win more. If you lose for decade after decade, like the Wallabies have at Eden Park, something needs to change. Targets can help with holding you to that.

So, construction costs may be high, and interest rates elevated—but that is reason to do more reform, not less. Australia will inevitably build less housing when construction costs surge. Incomes will dip during recessions. Growth will slow as lower-productivity sectors expand. The task of governments is to find ways to lose small—to ensure that in these bad times, we don’t go too far back. Even small policy gains compound. If good policy results in just one additional dwelling each year, or lifts productivity growth by 0.1 per cent annually, those incremental improvements will accumulate over time. We should not underestimate the power of compounding, even in cases where the numbers appear small.

Learning to speak supply

Reform is no fairy tale. There are always more problems to solve, more to do. Prices in Auckland are stabilising relative to incomes, but affordability has a long way to go. Outside the cities that reformed, rents have continued to climb, and out-migration to Australia has spiked post-pandemic. Some of the productivity gains that followed zoning reform have also unwound in recent years, as higher input costs and recession took hold.

Even the best-designed supply-side reforms can be overtaken by macroeconomic cycles. That doesn’t make them failures—things are better compared to what they would have been otherwise. Microeconomics works in the margins, not the headlines. Things will keep getting a little easier day-by-day, year-by-year.

Australia is, encouragingly, moving in the same direction. Both the New South Wales and Victorian governments have announced broad reforms to allow medium-density housing throughout Sydney and Melbourne, and higher-density development along transport corridors. And perhaps most importantly, the language has shifted: economists, policymakers, and the public are beginning to talk again about the supply side of the economy not as an afterthought, but as a necessity.

That shift in conversation may prove the real reform. Housing is, in some sense, the “Intro to Supply-side thinking” class. There is a clear constraint to lift and overwhelming evidence to support lifting it. If we can’t talk about this, we’ve got no chance for the next frontier. But if we get it right, we might be able to expand it to the next wave of progressive supply-side policies.

In our growing care sector, for instance, reform is far more nebulous. Nobody seems to have a clue what a tangible, implementable, policy change can be. To do so, we will need to re-think systems, not just processes. But the principles are the same: we figure out where reform delivers the most value, focus on bans rather than burdens, remind ourselves to get the market right—not just keep firms happy—and control the inputs we can control.

At its best, supply-side reform is the quiet work of expanding what’s possible. It doesn’t always make headlines; its benefits are diffuse, incremental, and slow. But over time, these benefits compound. If policy can keep bad times from becoming worse, or let markets build slightly more when conditions are tough, those small gains accumulate into something larger. The job of policy is not to win the cycle, but to raise the floor.

When we look back on the reform era of the 1980s and 1990s, it can appear simpler than it was. With hindsight the case for change feels obvious, so floating the dollar, deregulating finance, and cutting tariffs can read like a straight line. It was not. Those shifts took years of grinding policy work and a lot of persuasion. It meant telling stories: a warning that drift would leave Australia exposed, a counter-story that reform could deliver a larger, more confident economy, and a promise to hold course even when the cycle turned down.

The rhetoric of the time reflected that mix of urgency and faith. Keating’s warning that Australia risked becoming a “banana republic” without reform lit a burning platform, his claim that the 1988 budget was one which would “bring home the bacon” reframed the payoff from abstract economic reform into something tangible. Even the downturn that followed was reinterpreted as “the recession we had to have” - a necessary purge before recovery. Each phrase carried the same underlying lesson: trust the process, trust the settings, and don’t confuse short-term pain with long-term failure. These governments didn’t just cut red tape; they removed bans — on trade, on capital flows, on price controls — and placed faith in markets to adjust, even though they weren’t what all firms wanted to hear.

That instinct to link policy to possibility carried through to Keating’s later reflections on cities. Speaking to the OECD in 1995, he said, “We want cities that preserve the best of our past, celebrate the best of the present, and give a sense of the future—cities that people live in because they want to, not because they have to.” Two decades later, Edward Glaeser would speak in almost the same register. Like Keating, he told stories about places as engines of prosperity—about how cities foster connection, learning, and invention. In his telling, New York and Boston thrive because density lets people swap ideas as easily as goods; Detroit’s early carmakers learned from each other in real time, improving on each design in close proximity.

Glaeser did the analytical work — documenting how urban density drives innovation and growth — but, like Keating, he also found a way to sell it. In Auckland, his message landed deeply - to academics, to governments to policy wonks. A decade on, that story is still being written. But it’s also one we can begin to tell.

In the end, the lesson is as much about how we think as about what we build. Supply stories take imagination. They require us to picture the world not as it is, but as it could be. And it could be so much better than it is.

This essay, and its companion working paper, are written in my personal capacity, and neither should be necessarily attributed to the e61 institute.

People have mixed views of Steven Levitt and Freakonomics. I do like this little thought experiment though. Whatever you think of him, I’d recommend listening to this podcast about his experiences in economics, which is absolutely crazy.

For those curious, the reason shrimp consumption went up seems for reasons more tied to supply not demand: global production doubled over the 1990s, and has continued to grow further, particularly in Asia. This meant the real price of shrimp fell by about 50 percent between 1980 and 2002. Increased supply seems to have been driven by breakthroughs in Aquaculture technologies, dubbed the “Blue Revolution”, which have lead to enormous increases in yields.

Of course, this doesn’t mean these policies don’t exist. The first car I bought was a second-hand Hyundai, far cheaper than in a world where tariffs remained as high as they were in the 80s, for instance.

I’m not particularly interested in—nor am I particularly good at—writing on whether neoliberalism continues to reign supreme or died many years ago, on whether we overregulate or underregulate, on whether government is too big or is too small. I’ll leave these conversations to others. You should read this essay as “conditional on accepting that some supply-side reform is necessary…”

Alongside reducing sprawl and transport emissions, and city compactness. See Eleanor West’s excellent history of the changes in Auckland and nationally, or the 2013 Urban Growth strategy in Lower Hutt.

I will often start or end a section with text in italics, which usually will refer to a short vignette about housing policy which I think can neatly sum up an issue more generally.

With Joseph Gyourko and Raven Saks, among others

In this section I’m going to briefly summarise the zoning changes in New Zealand over the 2010s. For those who have heard these stories a hundred times already, feel free to skip to the next section.

There were also some reforms in Christchurch after the earthquake there in 2011, but I’ll skip over these for brevity.

Normalising housing construction to be on a per-capita basis is the best way to compare across time and across areas. You should be skeptical of anyone who uses other measures to make counterintuitive points.

Except for 2015, which was almost entirely driven by a single retirement village.

Defined as the average weekly rent as a share of average household income. This is, in my view, one of the better measures of affordability. It avoids weird compositional changes. For instance, imagine if rents fell (unambiguously increasing affordability), and this led to low-income young people moving out of home to rent, and high-income renters were now able to move into home ownership. This might worsen some affordability measures (e.g. the rent-to-income of renters) mechanically and would tell us nothing about affordability.

The US being the obvious exception to this.

You could also make the case that Australia’s construction productivity burst in the early 2010s was a temporary bubble due to infrastructure investment in mining states. Gianni La Cava has a good piece on this, and as I’ll show later, building construction productivity was consistently falling over this period.

The UK also climbs sharply from 2020 to 22, but this appears to be more compositional and COVID related rather than a genuine gain. The UK Office for National Statistics noted large compositional shifts in activity in 2020, as output fell, but labour fell by more. It’s plausible that lower-productivity work was put on hold over this period. I’ve used OECD data in the chart below for consistency, but in more recent ONS data, building construction productivity fell 15% from 2022 to 2024, back to 2011 levels. Although “Specialised construction activities” remains 20% more productive than pre-covid levels, for reasons I do not fully understand.

CEDA does find a slight bump in the mid-2010s which quickly evaporates, however. The Productivity Commission’s per-hours worked measure finds a steady decline over this period.

There are a few caveats to this story, including Christchurch earthquakes, the construction cost rises, and spillovers which are documented in my working paper.

For those fortunate enough not to follow the Wallabies over the last two decades, Australia has lost the Bledisloe series for the last 22 years in a row; in the 63 years it has been contested, Australia has only won it 12 times.

Technically the upzoning policy was only notified, rather than fully implemented during the overlap. But in Lower Hutt it began to influence development decisions from announcement (a fact you can glean from reading Resource Consents from this time period).

In the Productivity Commission’s 2018 Shifting the Dial report, for instance, the discussion of Australia’s land-use planning system centred on streamlining processes and reducing administrative costs.

The two references to zoning reform in the report are to a Harvard University working paper, and my work. Also, this shouldn’t be read as a critique of the PC (my former employer), or that report (which I think is quite good). But there is an open question about how valuable stakeholder consultation is

This is a less prominent but equally important example of status quo bias in consultation processes, as seen in community consultation on restrictive land use planning rules. consultations only talk to current residents, who have a vested interest in the status quo; but don’t consider future residents who are to gain from new development. This is before even considering how incredibly unrepresentative these processes usually are at engaging with a representative sample of even the existing population.

For example, the Productivity Commission estimates that National Competition reforms in the 1990s increased GDP by 2.5% in total. This is a meaningful increase, but labour productivity growth averaged 2.1% per year over this period generally. These things obviously interact, however.For example, the Productivity Commission estimates that National Competition reforms in the 1990s increased GDP by 2.5% in total. This is a meaningful increase, but labour productivity growth averaged 2.1% per year over this period generally. These things obviously interact, however.

For those interested in the technical reasons why this research broke down, it was because it treated household size as exogenous (i.e. there is some fixed rate that Australians want to live per person per dwelling) when in reality Australians form smaller households when housing is cheaper, and larger ones when it is more expensive. If you let this vary, there is no reason to believe the market wasn’t clearing - it was just doing so at a higher price than in a world where we built more housing.

I am pretty familiar with the planning and cost of housing stories of this upzoning, as an Auckland resident involved with urban development, but the insights on construction industry dynamics and productivity were new to me. I guess thay should not have been a surprise! Thanks for the great analysis!