Opening editorial: The Spirit of Progress

A strong point of view well-written can move the needle on policy.

A few updates from the Inflection Points team

Our launch made a splash

Since we launched one week ago, Inflection Points has seen a wave of support and engagement:

We’ve had endorsements from a wide spectrum, including leading Australian economist Chris Richardson, as well as Ben Southwood (from Works in Progress)

We reached more than 2000 subscribers, and many thousands more on-site readers

Our launch event, Moving the Needle, is more than 50% sold out

The Problem with Urban Planning was referenced in the ABC, and a shorter version of the essay was published in the Financial Review. Data has been reproduced for New Zealand and for the United States.

What this mailer is for

Between editions, we’ll share the top articles from Inflection Points directly to your inbox. Below, you’ll find a copy of The Spirit of Progress, our opening editorial. It details our vision, and what we hope to achieve with Inflection Points.

The Spirit of Progress

Manning Clifford & Jonathan O’Brien

Australians love to talk about the need for reform. Sometimes, it seems we love these conversations so much that the discussion itself becomes the point. Opportunities for real, meaningful reform are rare in Australia, as they are across the world. But if today is to be one of those opportunities for reform, then we must ensure we are ready for it.

Inflection Points hopes to help prepare Australia for such an era of reform by commissioning leading thinkers to reflect on and advocate for major change. Before we introduce our editorial perspective, we want to look back in history for inspiration and instruction. And so we find ourselves in the 1800s, where—much like today—Australia stood at a crossroads, full of promise yet divided in vision.

A story of change

All it took to divide a continent as vast as Australia was a few inches. As each colony expanded their vital rail networks throughout the 19th century, each selected a different track gauge, reflecting their own parochial priorities rather than any shared national vision. Victoria and New South Wales had initially planned to coordinate with broad-gauge lines—but New South Wales adopted standard gauge after a last-minute change, leaving the two large colonies out of step. Meanwhile, Queensland became the world's first railway operator to adopt narrow gauge for a main line, driven by both lower costs and greater manoeuvrability across mountainous terrain.

And so what might have served as the backbone of a growing continent instead became a patchwork system where every border created a break in movement. These breakages reduced trade between the colonies, hampering economic growth. Even in the mid-1900s, more than a dozen breakages still bottlenecked our nation's transport system, requiring manual transfer of both freight and passengers alike.

So painful was the experience that, when recounting an Australian journey in Following the Equator, Mark Twain wrote:

At the frontier between New South Wales and Victoria our multitude of passengers were routed out of their snug beds by lantern-light in the morning in the biting-cold of a high altitude to change cars on a road that has no break in it from Sydney to Melbourne! Think of the paralysis of intellect that gave that idea birth; imagine the boulder it emerged from on some petrified legislator's shoulders… It is a narrow-gauge road to the frontier, and a broader gauge thence to Melbourne… All passengers fret at the double-gauge; all shippers of freight must of course fret at it; unnecessary expense, delay, and annoyance are imposed upon everybody concerned, and no one is benefitted.

For much of the 20th century, this dysfunction was tolerated. It was viewed as too expensive to fix and too difficult to coordinate. Other nations, including the United States, had resolved this challenge nearly a century earlier, standardising vast networks of track across enormous geographies with remarkable speed. Australia, by contrast, spent decades putting up with and generating piecemeal patches for the challenge of mismatched gauges.

A commitment to improvement

The story of gauge standardisation in Australia is not a short one. And it starts, of all places, in Columbus, Ohio. In 1900, Harold Clapp, then a 25-year-old tram operator in Brisbane, moved to the United States to work with General Electric and then later Columbus Railway Power. Across the United States, he saw progress abound in their railway network, including the mass electrification of suburban railways across the country. By the end of his career across the Pacific, he had worked his way up to Vice President of the Southern Pacific Railway Corporation.

Following his successes in the States, Clapp returned to Australia to serve as Chairman of the Commissioners of Victorian Railways. At the time, his salary of £5,000 was the highest among all public servants in the country. When he took up his new post in 1920, he laid out his priorities to an inquiring interviewer, stating ‘I am all for efficiency and teamwork”. His slogan for the department was “Help us help you’.

And help Victorians he did. His countless achievements in the role led to him being labelled ‘Australia’s most remarkable public servant’. He electrified Melbourne’s metropolitan railway network, renewed timetables, and commercialised Victoria’s railways by establishing ancillary revenue lines, including food canteens and even a crèche at Flinders Street Station. A Herald editorial suggested that this success was due to a commitment to excellence paired with a humble, service-led approach, writing that:

The secret of Mr Clapp's success as a Railway Commissioner is that he has done the obvious things thoroughly… It is quite obvious that the railways belong to the people, and that their business is to serve the people. The present efficiency of every branch of our railway service is the direct result of Mr Clapp's success in giving the railway men a respect for and a pleasure in their job.

The most ambitious of Clapp’s projects, however, was yet to come. Having seen what was possible overseas, Clapp was determined to elevate Victoria’s railways to world standards, and so he launched the development of a new railway line that would constitute a leap in the quality of Australian manufactured trains.

Launched in 1937, these engines were world class: fully air-conditioned, all steel, and streamlined to run express. Token signalling enabled non-stop journeys on single-line tracks, and engineers calibrated corners with a bowl of soup—any spillage as the engine turned meant the train was too fast or the curve too sharp, and adjustments were made.

Before its launch, Gertrude Vivian, Clapp’s wife, coined the line's fittingly ambitious name: the Spirit of Progress.

Limits on progress

That spirit was stymied, however, at the border between Victoria and New South Wales, where broad gauge met standard gauge at Albury. Even by 1937, Australia hadn't established a modern, affordable and high quality rail link between its two largest cities. The Spirit of Progress was stalled.

For decades, Victoria’s investment in world-leading rail infrastructure was hampered not by insurmountable or technological constraints, but by the inability of Australia’s leaders to confront an issue which had been solved nearly a century earlier across the globe.

In 1942, Prime Minister John Curtin appointed Clapp the Director-General of Land Transport. He was charged with rationalising a rail network that now posed a strategic liability in light of the outbreak of World War II. The gauge breaks across the nation's rail network required hundreds of workers to manually transfer mission-critical cargo between rail cars, sometimes over the course of multiple days. And so, as is often the case, it took a crisis to convert Clapp’s commitment to standardisation and efficiency into real, meaningful change. To catalyse his strong beliefs into policy action, Clapp took to the typewriter.

An inflection point

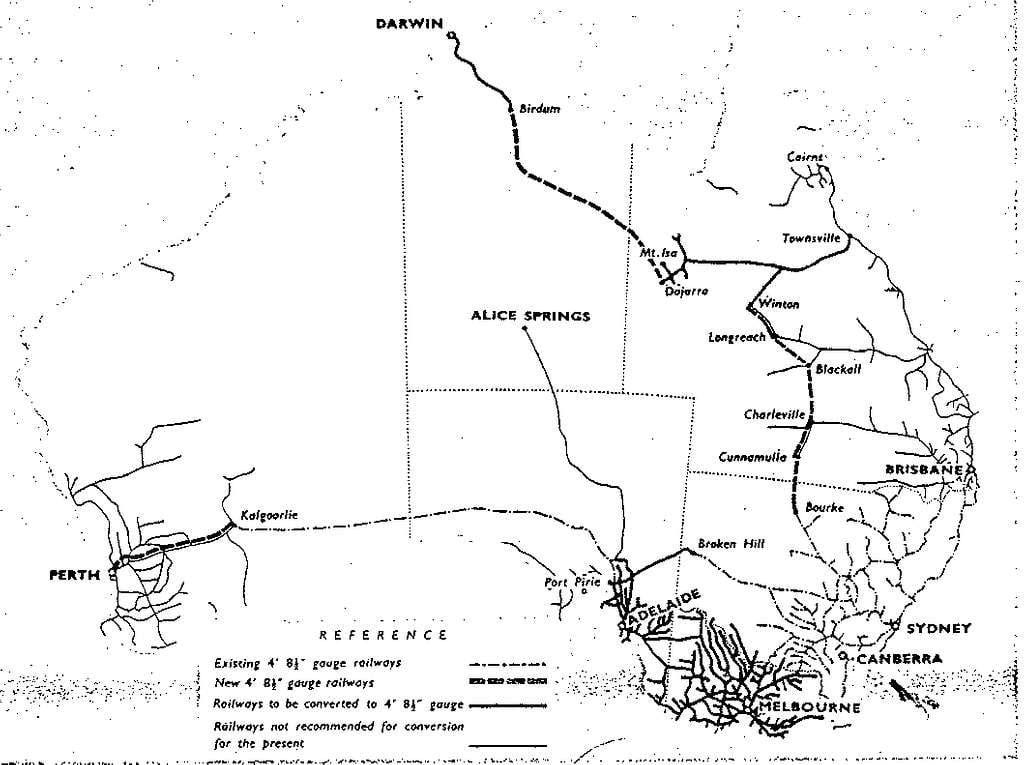

Clapp’s 1945 report, titled Standardization of Australia’s Railway Gauges, was a landmark piece of policy writing: it proposed converting more than 6,000 miles of track across every mainland state to standard gauge, backed by a £44 million investment—almost $4 billion in today's dollars.

In the report, Clapp detailed the cost of Australia’s fragmented rail network. But he also outlined the gains standardisation could offer: a rail corridor from Brisbane to Perth would connect markets, support growth, and strengthen the federation. He specified (with dotted lines on a map) new tracks to be built or transformed into standard gauge.

He also specified a broader hope for a country which was, at the time, fractured along state lines, writing that ‘standardization of gauges will in no small measure tend to break down state prejudices and be an ever-growing influence in developing a national, as opposed to state, outlook’. Clapp was thinking beyond railways, about the nation he hoped to build for the future.

What is most striking about Clapp’s report is his precision of language and ability to create urgency. In concise, forceful terms, he laid out the case for change in a way that galvanised policymakers. In the conclusion of the report, he wrote:

From any serious study of this subject two paramount facts emerge:—Firstly, that for the safety and well-being of this great country, standardization of railway gauges will ultimately have to be undertaken (that has been demonstrated only too clearly by the world war); and secondly, that the longer it is deferred the more costly it becomes. [...] It is therefore highly important that a decision be reached as early as practicable.

Three years after Clapp’s death in 1952, the Commonwealth and the states agreed to construct a standard-gauge line between Melbourne and Sydney. In 1962, the line from Melbourne to Albury expanded north to Sydney.

Today, trains travel from Brisbane to Perth without a single gauge break. This saves countless hours of unnecessary waste every year. The fragmentation that once defined the network has been overcome. But few appreciate the enduring efforts required to reach this point, and the national vision that made this a reality.

Our theory of change

We believe that the understated service to the nation undertaken by Clapp and the many unsung heroes like him is worth emulating, in hope of a better future for all. In the spirit of Clapp’s ambition to improve Australia, we launch Inflection Points. Inflection Points commissions and publishes long-form writing and research that engages with the institutions, analysis, and reforms required to build a bigger, better Australia.

We don’t purport to solve the structural and political barriers to implementing many of these reforms. But we do think there’s a gap in political discourse that we can help fill; that is, a gap between the short form op-eds that give top-level answers and the hundreds-of-pages-long reports that go into more detail than can be digested.

Our ambition is to answer the harder questions that these formats often struggle to confront head-on: What does meaningful reform require—technically, institutionally, and culturally? What tradeoffs must we make? What must we do today, for the sake of tomorrow?

Our point of view

We believe that quality writing and advocacy—like Clapp’s—can help Australia confront the challenges that have plagued us for generations. As a platform for quality long-form policy writing, we aim to disrupt the short-term, piecemeal approach to reform that has defined the past thirty years. In this context, we bring a rigorous, unapologetically pro-growth perspective to Australian policy. Our opinionated editorial view is built on three key principles.

We believe in abundance. We believe in an abundant Australia, where prosperity is expansive, inclusive, and continually growing. To confront the challenges of tomorrow, economic growth will inevitably be at the centre of many, if not all, of our solutions.

We are committed to an Australia for all. We support an Australia that makes its egalitarian aspirations a reality. As one of the most equal and mobile wealthy societies globally, we must ensure that our abundance continues to reach those who need it most. Central to this vision is a fair, global, and multicultural Australia that engages with its region.

We value depth and long-term thinking. We champion long-form policy writing because complexity demands depth. Australia’s policy challenges cannot be distilled into soundbites, let alone the associated solutions. Inflection Points pieces provide concrete insights, analysis, and recommendations with the potential to move Australian policymaking forward.

We are not aligned with any political organisation or party and we strive to bring a balance of opinions from across both Australian society and the aisles of parliament.

Our focus points

Today, there are a handful of areas which we believe offer the most promise for building Australian prosperity. In light of this, most of the content we commission is focused on four key themes:

Increasing state capacity. Countless pieces show a strong link between state capacity and citizen outcomes. Given this, we’re looking for ways to improve Australia’s already strong public sector capability, accountability, and delivery, empowering governments to meet today’s challenges even more effectively.

Building infrastructure and housing. Housing and infrastructure costs in Australia are higher than they should be. We’re interested in ideas that help to unlock new housing supply, upgrade transport and energy systems, and deliver new infrastructure to support a growing population.

Supporting productivity growth. Productivity growth in Australia has been its slowest in sixty years, yet it remains critical for improving living standards. We’re keen to hear about smart reforms that can boost economic dynamism. This means pieces focused on tax, regulation, tech adoption, industrial policy, education, and more.

Enabling human flourishing. Social connection in Australia has declined rapidly in past decades, and critical government services are becoming more costly to deliver. We welcome ideas that strengthen education, health, migration, and social support systems.

As Australia’s context evolves—and as progress is made on these challenges—we too will evolve our focus. Where we believe a novel topic deserves attention, we will dedicate appropriate space for discussion of it.

Our aspiration

In Clapp's 1944 report, a dotted line indicated a railway line not yet built, a link imagined but unrealised. Such lines remind us that national progress begins with a vision that is both specific and ambitious.

These dotted lines feature heavily in our digital identity. From our masthead to the column inches of our digital broadsheet, they mark the potential of a country that dares to dream and build bigger. Our great hope for this publication is that we might help some of these sketched lines become solid, and enable the spirit of progress to spread across Australia once more.