The Problem with Urban Planning

A professional monopoly is gatekeeping our growth. We need a new paradigm: planning at the speed of cities.

By Jonathan O’Brien

At the first council meeting I ever attended, 39 new homes were blocked. I hadn't chosen the meeting because I'd expected this to happen; I'd chosen the meeting to speak in favour of converting a derelict heritage house into two townhouses, which was ultimately approved. But what I saw there that evening stunned me: the squeaky wheel of local opposition had moved the Council to make a real reduction in housing approvals.

This experience helped inform YIMBY Melbourne’s initial thesis: that the cause of bad land use regulation was hyperlocal political decision-making. Local governments knock back and cut away at high-quality projects, including social housing, primarily—we figured—because they are politically captured by a small minority of voters.

But this is not the full story.

While many of the most headline-grabbing and absurd planning decisions are made by elected councillors, the actual restrictiveness of the controls and their broad implementation cannot be attributed to elected representatives alone. Indeed, most councillors barely understand their zoning codes, and their positions on planning matters are held mainly in reaction to what they hear from some loud minority of their voters.

It is hard to blame councillors for not being across the entirety of their planning systems. These systems are complex, primarily regulatory, and comprise a set of overlapping tools like zones and overlays that, when taken together, dictate what can be legally built on any given piece of land.

The planning system controls the type of land use—residential, commercial, industrial, and so on—as well as the heights and densities permitted. Planning also controls the built form of our cities in various ways, but it's worth noting that these are not building codes, which are handled comprehensively by the National Construction Code (NCC). Planning codes are ancillary to the NCC's core health and safety requirements.

The problem with planning controls is that they tend to be restrictive rather than permissive. An example of what we call 'restrictive zoning' is Victoria's Neighbourhood Residential Zone (NRZ), which only permits two storeys of development across almost half the residential land within 15 minutes' drive of Melbourne's CBD. The downstream results of bans on density like these is a scarcity of inner-city housing options, higher housing costs, and a less vibrant city for those who live here.

But it is not just councillors who decide to ban density. Behind elected representatives are teams of professional planners who do understand restrictive zoning policies, and who are applying and enforcing them anyway.

This became clear to us as YIMBY Melbourne gained prominence within public debate. Online and in person, some members of the planning profession, facing external scrutiny for one of the first times in their careers, began to publicly defend their restrictive planning work.

This sharpened our vision significantly: for these planners, there were no local political incentives, no homevoters, neighbourhood defenders, or city-haters determining their next election outcomes—and yet they earnestly believed in the virtue of banning more diverse housing options in the places where people most wanted to live.

One way to explain the proliferation of restrictive land use regulations across our country, it turns out, is that many of the people in charge of these rules are well-meaning, and believe that they are doing a good job.

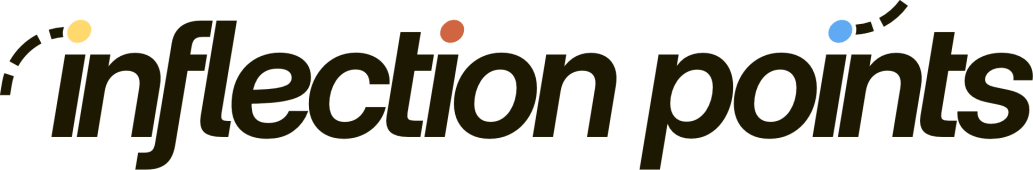

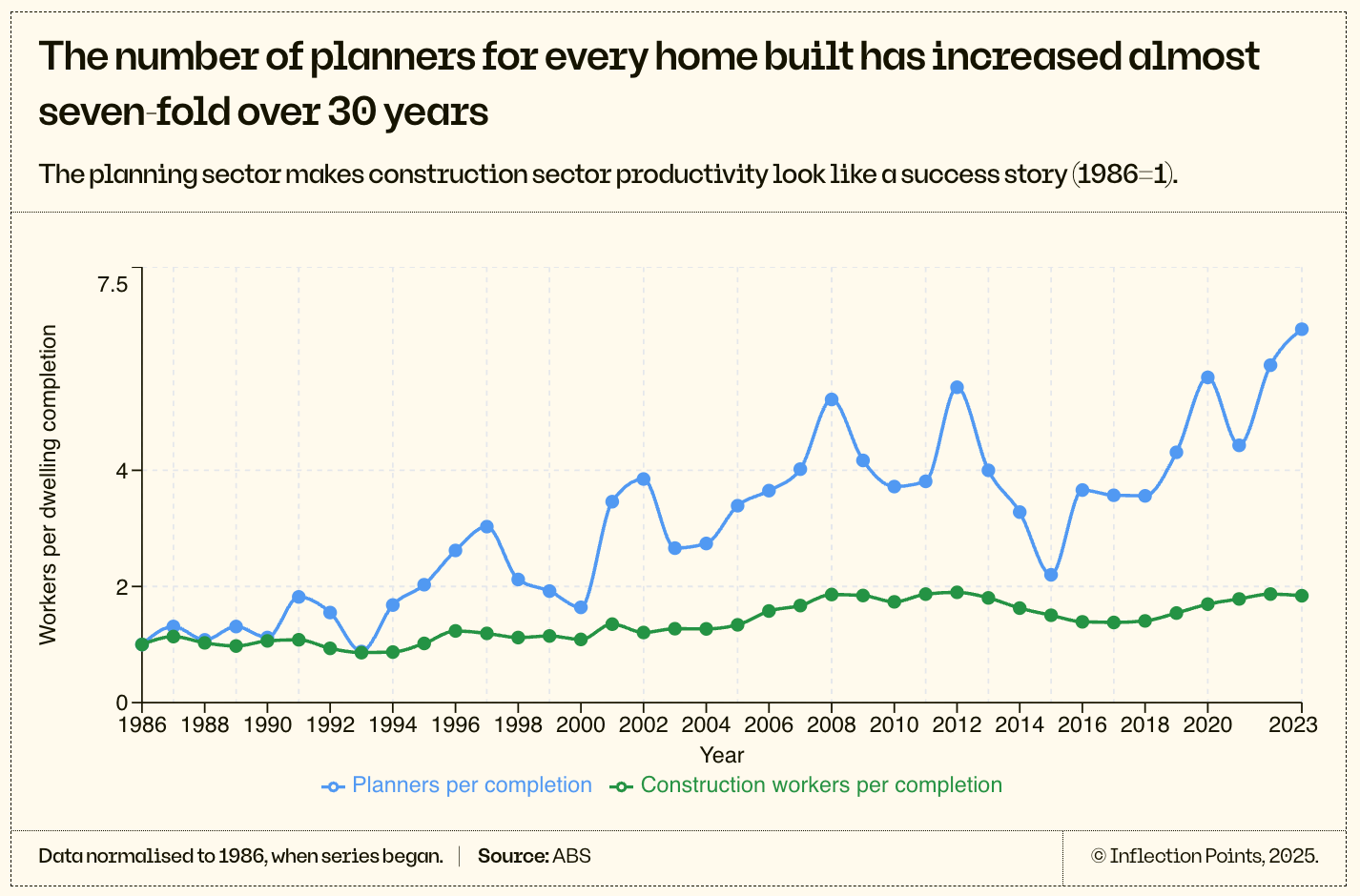

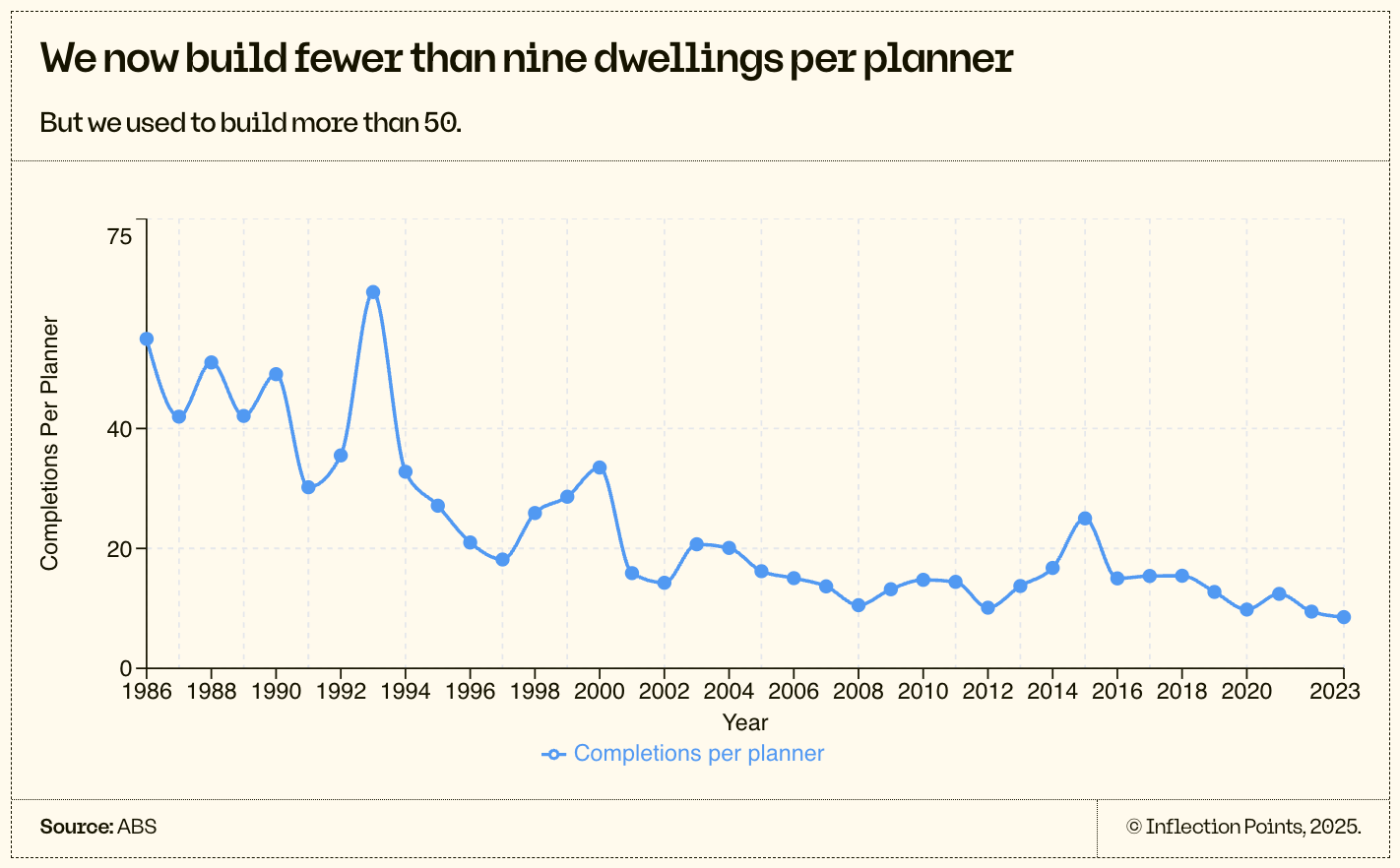

And these people have a great amount of influence over the shapes of our cities. Since the 1980s, that influence has grown enormously. There are almost nine times as many planners today as there were in 1986. But while for every planner in 1986, we built more than 50 homes, we now build fewer than ten homes per planner. In the face of a generational housing shortage, the productivity of planners makes the notoriously struggling construction sector look efficient.

Meanwhile, the Planning Institute of Australia has declared an emergency planner shortage. But given the sector's monumental growth, it seems much more likely that what we face, rather than a shortage of planners, is an excess of planning.

To understand this, one needs only to look at the outcomes.

In the 21st century, planning timelines have mainly lengthened. Housing shortages have grown more dire. In response, planners have invented new, complicated fast tracks—only for projects to still get blocked at the finish line. In the energy space, the Victorian planning system is currently delaying more than $90 billion worth of renewables, and it is becoming more and more likely that we will be forced to subsidise offshore wind—with its similar cost to nuclear power—because the planning system makes it virtually impossible to build enough renewables on land.

All of this has been allowed to happen because planning policy has been monopolised by a small professional silo, which for decades has been insulated from external input, feedback, and oversight. This isolation has left planners both culturally and operationally out of step with the rest of government, to the detriment of our nation's wellbeing and our governments' capacity to deliver for their constituents.

This silo is underpinned by a set of unsubstantiated frameworks that are generally ambivalent—or worse, actively hostile—to economic growth, to markets, and to government delivery and national prosperity as key goals of policymaking. From here on, we will refer to this pervasive constellation of old-school norms, beliefs, and practices as 'legacy planning'.

Not all planning practitioners are legacy planners. Many, of course, are frustrated by the restraining norms of their profession. A younger generation of more progressive planners, trained in the modern age of urbanism, internationalism, and the immense promise of the city—these people should give us some hope for the profession moving forward.

But this new generation of planners will struggle to undertake reform from within. The deep entrenchment of esoteric beliefs and archaic practices within the profession means that the only reliable path to reform will be by shattering the silo altogether.

Doing so will open land use policymaking to new possibilities. It will enable governments to move away from an onerous system of processes and toward a contemporary model of tradeoffs and delivery. These new forms of planning practice will be faster, more iterative, and oriented by outcomes. Under a new model of 'iterative planning', land use policymakers will be empowered to move beyond the system's current status quo bias and toward a more progressive form of policymaking, which one might call—planning at the speed of cities.

Jonathan is the editor-in-chief of Inflection Points and the lead organizer of YIMBY Melbourne.

The full version of this article is published here.