The Abundance Agenda for Australia

Across housing, infrastructure, energy and research, Australia faces a common challenge: not a shortage of ambition, but a shortage of delivery.

By Andrew Leigh

For nearly 2 decades, my wife Gweneth and I have lived in the Canberra suburb of Hackett, where we’ve raised our 3 boys. The suburb backs onto Mount Majura bush reserve. It has a modest but functional shopping strip: a supermarket, a café, a bike store. The houses are sturdy, unflashy, and uniform – typical of the mid‑century Australian public housing aesthetic. They weren’t designed to win awards. They were designed to meet need.

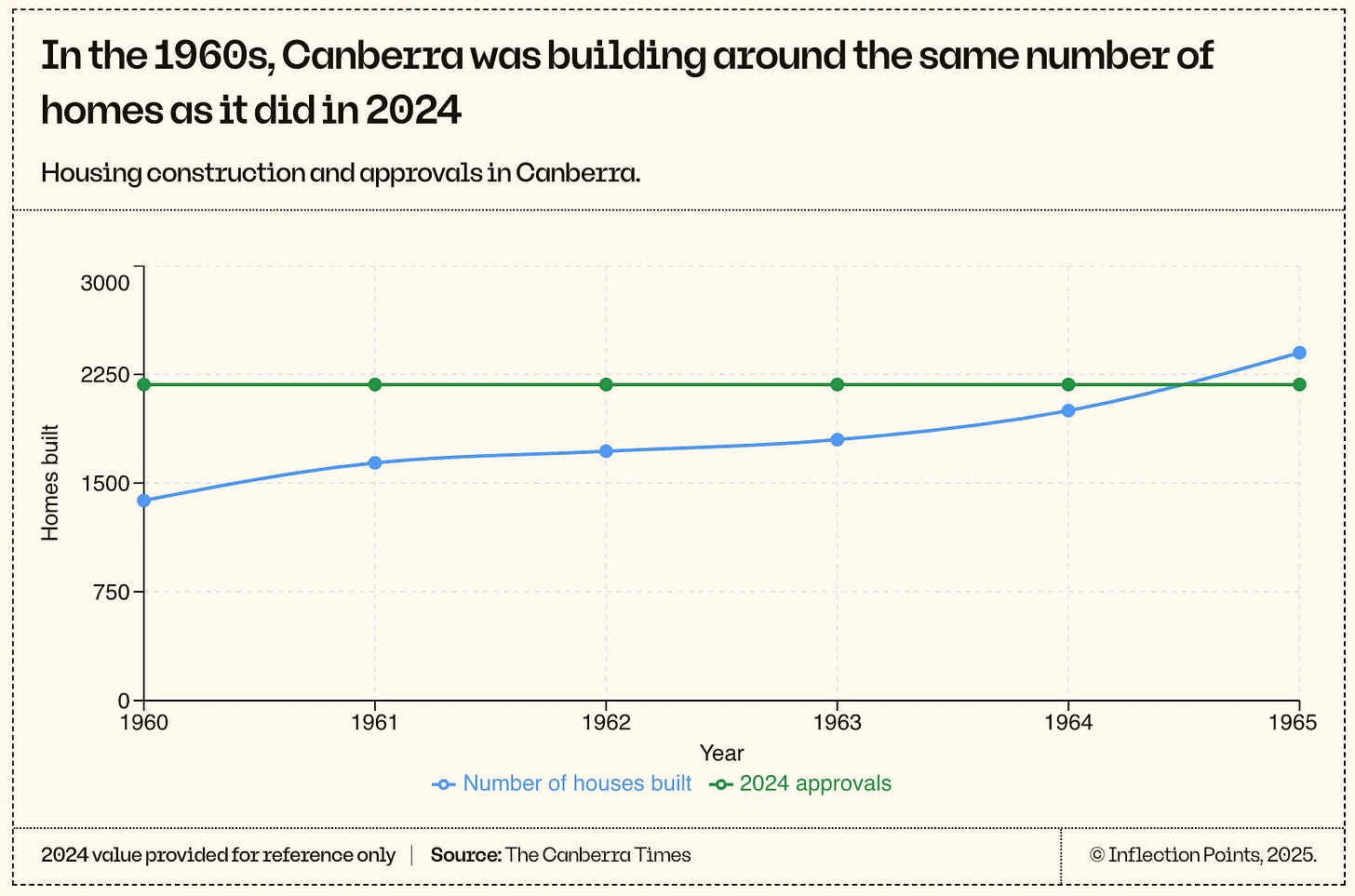

Hackett’s growth was rapid. In 1963, the suburb had just 156 residents. By the end of 1964, it had grown to over 2,000. Builders such as Clayton Homes, ACT Builders, JJ Marr and AV Jennings worked under contracts that required homes to be delivered in 6 to 9 months. The Canberra Times described the pace as ‘breathtaking.’ In the 1963–64 financial year alone, 604 homes and flats were built in Hackett. By the mid‑1960s, the broader Canberra region was delivering over 2,400 dwellings annually – impressive for a city whose population was then under 100,000.

These homes weren’t architectural masterpieces. But they were delivered fast, built to last, and priced within reach. Many are still standing, still lived in, still serving the purpose they were built for. That was abundance in practice – not abundance in opulence, but in accessibility.

Fast‑forward to the present, and the contrast is striking. In 2024, just 2,180 dwellings were approved in the entire ACT – the lowest annual total since 2006, and less than half the number approved the previous year. Over the past 15 years, the ACT has averaged around 4,700 approvals annually. The collapse in supply isn’t just a statistic – it’s a signal.

The decline is especially acute for the kind of housing that fills the space between detached homes and apartment towers. In the second half of 2024, just 7 significant development applications – those typically covering townhouses and other medium‑density formats – were processed in the ACT. None were approved within the statutory timeframe. The median wait was 117 working days. The longest took 192.

To its credit, the ACT Government has acknowledged the problem. A new outcomes‑based planning system, introduced in 2023, was intended to provide more flexibility and clarity. But with greater flexibility came greater complexity. Documentation requirements grew. Timelines slowed. Builders and applicants struggled to adapt.

ACT Planning Minister Chris Steel puts it bluntly: ‘Townhouses, terraces, walk‑up apartments, are effectively prohibited in most residential zones in Canberra’. The ACT government’s draft Missing Middle Housing Design Guide is an attempt to break that pattern – to promote ‘gentle density’ options that align with existing neighbourhoods while expanding supply.

What the story of Hackett reminds us is that housing abundance doesn’t require revolutionary architecture or lavish public spending. It requires systems that work – contracts that deliver, approvals that flow, and institutions that see housing as something to enable, not impede.

The abundance agenda

When we talk about abundance, it’s easy to picture extravagance – glut, excess, waste. But in their new book, Abundance, US journalists Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson argue for something more grounded, and more urgent: the idea that a rich society should be able to meet its people’s basic needs – housing, transport, energy, education – quickly, affordably, and at scale.

And yet, across the developed world, we’re falling short. The problem isn’t a lack of wealth, or ideas, or demand. It’s the quiet accumulation of obstacles. The book catalogues example after example of systems that are so tangled they can’t function.

In San Francisco, Klein and Thompson note that it takes an average of 523 days to get clearance to construct new housing and another 605 days to get building permits. This is one reason why the median home in that city now costs US$1.7 million, compared with US$300,000 in construction‑friendly Houston. The difference isn’t scandals, corruption or villains – just a tangle of approvals, agencies, consultations and codes.

Similar problems afflict the ability of the United States to build high speed rail and renewable energy, provide affordable higher education and healthcare, and support breakthrough university research.

The duo argue that this has had a direct impact on the wellbeing of many Americans. As they put it, ‘We have a startling abundance of the goods that fill a house and a shortage of what’s needed to build a good life.’

The deeper point isn’t about permits or flat‑screen televisions. It’s about what happens when systems stop being built for delivery. When process becomes the product. When every interest group has a veto, but no‑one has a deadline.

Klein and Thompson call this the ‘abundance crisis’ – a situation in which society has the resources to solve big problems, but the machinery of action has rusted.

Their argument isn’t anti‑government. It’s pro‑capacity. They want to design systems that are actually fit to deliver the public goods we keep promising. They believe in ambition – but only if it’s backed by execution.

Harvard’s Jason Furman adds a useful provocation. Furman, the former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Obama – warns that progressives can make the mistake of believing that all good things point in the same direction. That climate action, job creation, housing supply and inclusive employment practices always align.

In reality, Furman says, policy is frequently about trade‑offs. Not everything desirable is mutually reinforcing. Not every worthwhile project can be done without cost or controversy. If we’re serious about delivering on progressive goals, we have to make hard decisions – and be honest about them.

Klein and Thompson’s book centres on the United States, a country with a political culture quite different from our own. So we shouldn’t expect its arguments to transfer neatly to the Australian context. Still, the book makes a compelling case that progressives must care about supply – a message that resonates here too. Abundance contends that the politics of progress requires a revival of production. A society serious about decarbonising, housing its people, and fostering a knowledge economy must also be able to string the wires, build the homes, and support the labs.

In short, abundance isn’t about utopia. It’s about competence. About saying yes – not to everything, but to the right things. And doing it before the opportunity passes.

Note: This is a republication of a speech that Andrew Leigh delivered to the Chifley Research Centre on 3 June 2025. The Inflection Points editorial team have included graphs from papers referred to in the speech. The author gives his thanks to Dan Andrews, Jonathan O’Brien, and many colleagues and officials for insightful feedback on earlier drafts.

Andrew is the Assistant Minister for Productivity, Competition, Charities and Treasury.

The remainder of this article is published in full on Inflection Points.