Technology Can Address Care Worker Shortages

Australia’s care sector is not set up to adopt new technologies that would improve its efficiency. It should be.

An update from the Inflection Points team

Jonathan O’Brien, our editor-in-chief, is hosting a live podcast in conjunction with Effective Altruism Australia in a few weeks. They’ll be discussing fixing Australian philanthropy. The event will be held at 7pm on Wednesday February 25 at the State Library of Victoria. Get tickets for the event here. Not in Melbourne? Subscribe to the Inflection Points Podcast to hear the recording after the fact.

The article below, written by Jade Lin, was published in edition two of Inflection Points in November last year.

My mum looked after my grandma in her final years. She helped her bathe, drove her to appointments, took her for walks in the park. My grandma got to stay at home until near the end, when her cancer got too much and she went into palliative care.

My grandma had just about the best last few years she could have hoped for because my mum is a superhero. But what if my mum hadn’t been there?

1.4 million Australians will be funded by the Australian Government under its Support at Home program to have personal care support by 2035, and many others will self-fund it. Over a million Australians will be on the NDIS, many of whom will also require personal care.

Millions of us at any given time will be asking personal care workers to help us go to the toilet, swallow our medicine, or get out of bed. These are strangers who we are trusting with our bodies in our most vulnerable time. This is a critically important workforce.

But despite their importance, in the coming years we’re likely to face a shortage of these workers. Central to both of those challenges is that care is a deeply human job: it’s really hard, and it’s slow to innovate.

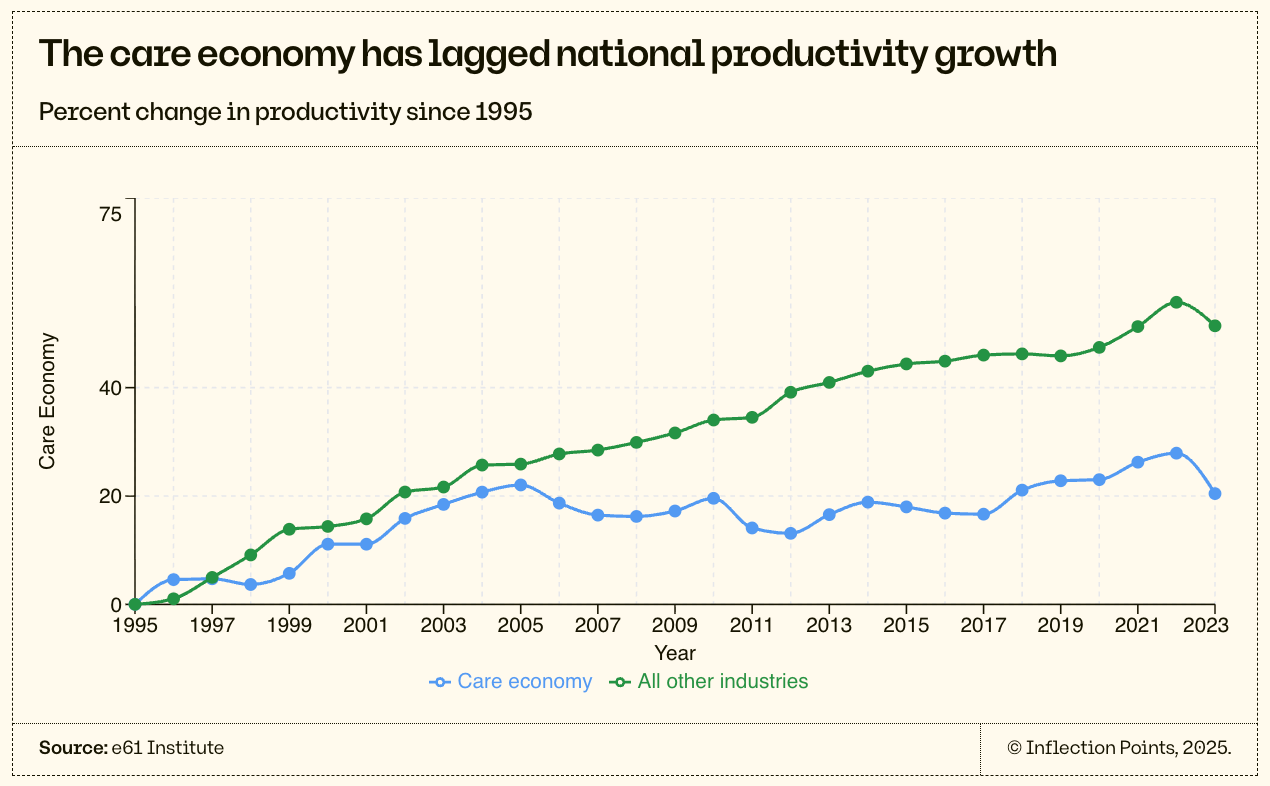

In a national conversation about how we supercharge the economy with AI and other emerging technologies to make it more productive , it’s worth asking whether that applies to the care economy too. Historically, the sector has been dismissed as inherently low-productivity, due to slow productivity growth over the last three decades: in 2025, a carer can only physically help so many people in a day, whereas with the help of spreadsheets and computers a junior analyst at a bank can fly through the analysis of yesteryear. In this school of thought, as the care sector grows to comprise more of the economy, we should expect it to drag down aggregate productivity as well.

But this is an unnecessarily defeatist and bleak attitude. The care economy allows other more productive sectors to thrive—after all, a highly productive worker with an ageing mother can only go to work if their mum gets help. That’s why it’s important that we get the policy settings right.

There are many productivity gains still to be had within the sector. Many tools already exist that let carers increase both their quality and volume of care, but most are slow to be widely adopted in this fragmented industry. Yet the frontier for care is seldom closely examined. It’s a tough job, for sure, but could it be marginally less so with clever technological assistance? The work is low-paid for now, but can we share the gains of new efficiencies with workers?

This piece considers these possibilities, and what they might mean in the context of a highly regulated and often poorly functioning labour market for care economy workers.

We need more personal care workers

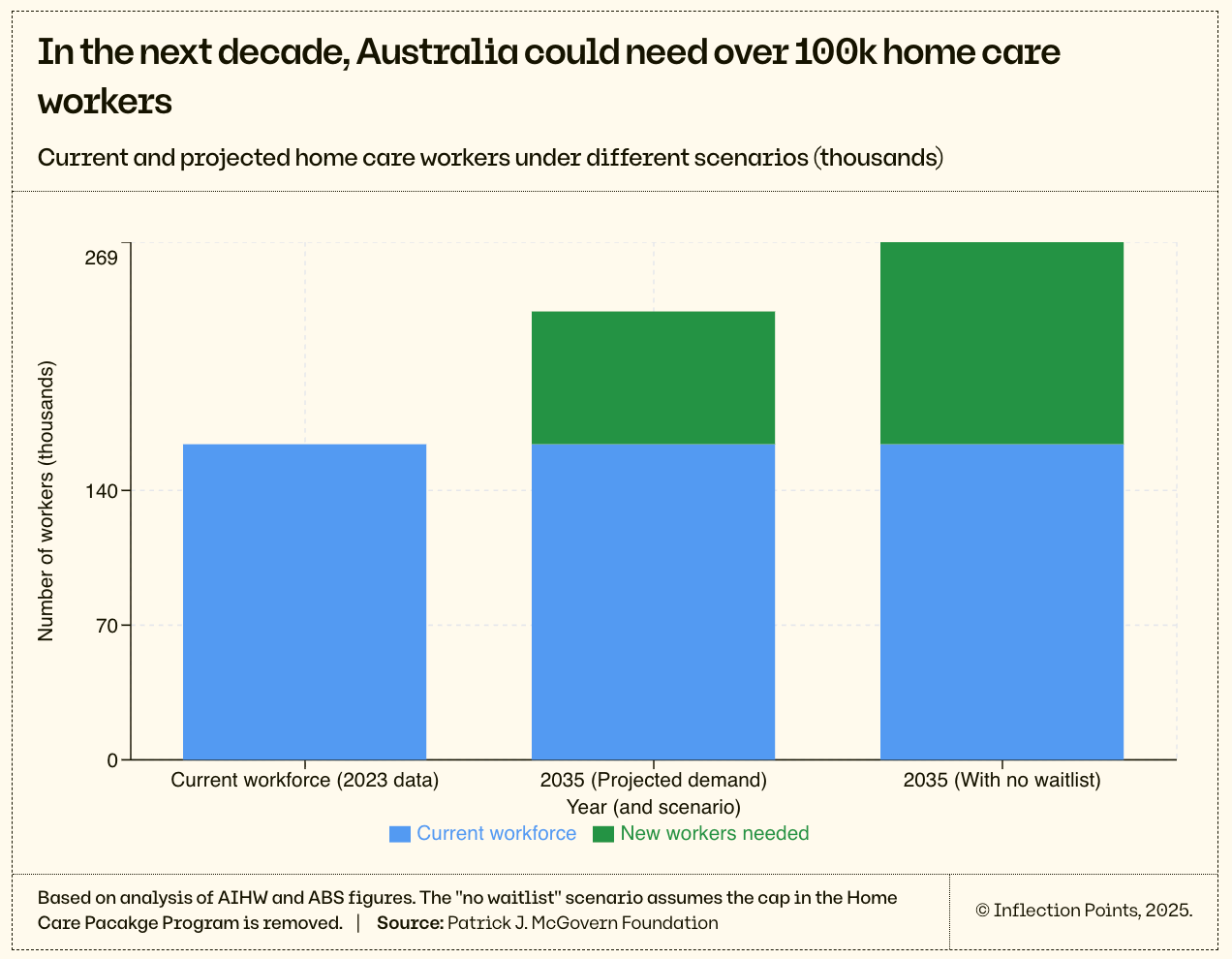

Demand for personal care for older people at home is expanding as the population ages. In 2035, more than 20% of Australians will be over 65 compared to 13% in 2009. 5% of the Australian population will receive home care funding from the Australian Government, compared to 4% today, and 3% in 2017.

To maintain the current ratio of personal care workers to older Australians, the number of people working in older people’s homes needs to expand by 42% between 2023 and 2035. If we removed the cap on home care package funding that drives the current “waitlist” model, we would need an enormous 62% expansion of the personal care workforce.

The Aged Care Royal Commission’s interim report condemned the “waitlists” older people endure as cruel and discriminatory. It noted that many older people died before receiving their packages, or were prematurely moved to residential care because of their place on the “waitlist”. Since then, the formal “waitlists” to access packages have lengthened, and staff shortages mean that even when you reach the front of the queue, in some areas, there are no providers to supply those services to you.

We lack good data on care shortages

Tackling Australia’s care sector future requires understanding where the most acute shortages will occur, and when. This analysis is severely constrained by the Australian Government’s current data collection. It is surprising—given that aged care has been at the forefront of policy discussions for at least a decade—that the only way to get useful workforce data on aged care at home is to rely on a sporadic survey (the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare GEN Aged Care Data Aged Care Provider Workforce Survey).

I wanted to know how many home care workers there are working in aged care contexts. Straightforward enough, right? Turns out, not so much. The ABS offers the relevant category: ‘Personal Care Assistant’ (ANZSCO 423313), and Jobs and Skills Australia tells us that there are 42,300 people doing this job. But then it also has ‘Aged or Disabled Carer’ (ANZSCO 4231), which Jobs and Skills Australia reports to comprise 367,200 workers. The tasks listed in those jobs are overlapping, and the contexts in which they’re done are unextractable—we can’t know if they’re being done in a residential care facility, at home, or in a hospital.

Compare these two broad categories to the intense specificity offered in other sectors of the economy—such as fire protection plumber (334117), vehicle trimmer (351532), driller’s assistant (821931) or lagger (821932).

This leaves us with limited data on the specific shortages of care workers. From the same survey that these projections are built on, we know that in March 2023 there were 43,000 vacancies in directly employed nursing, personal care, and clinical care manager positions across all aged care. What proportion of those vacancies were in home care, and how many were covered by contractors and overtime is unclear—meaning we cannot actually know the existing shortfall in home care workers.

As such, consider 43,000 the lower-bound of the number of additional workers actually needed. The real number may be much larger, and even meeting this lower-bound target will be no easy feat.

Care sector jobs face problems

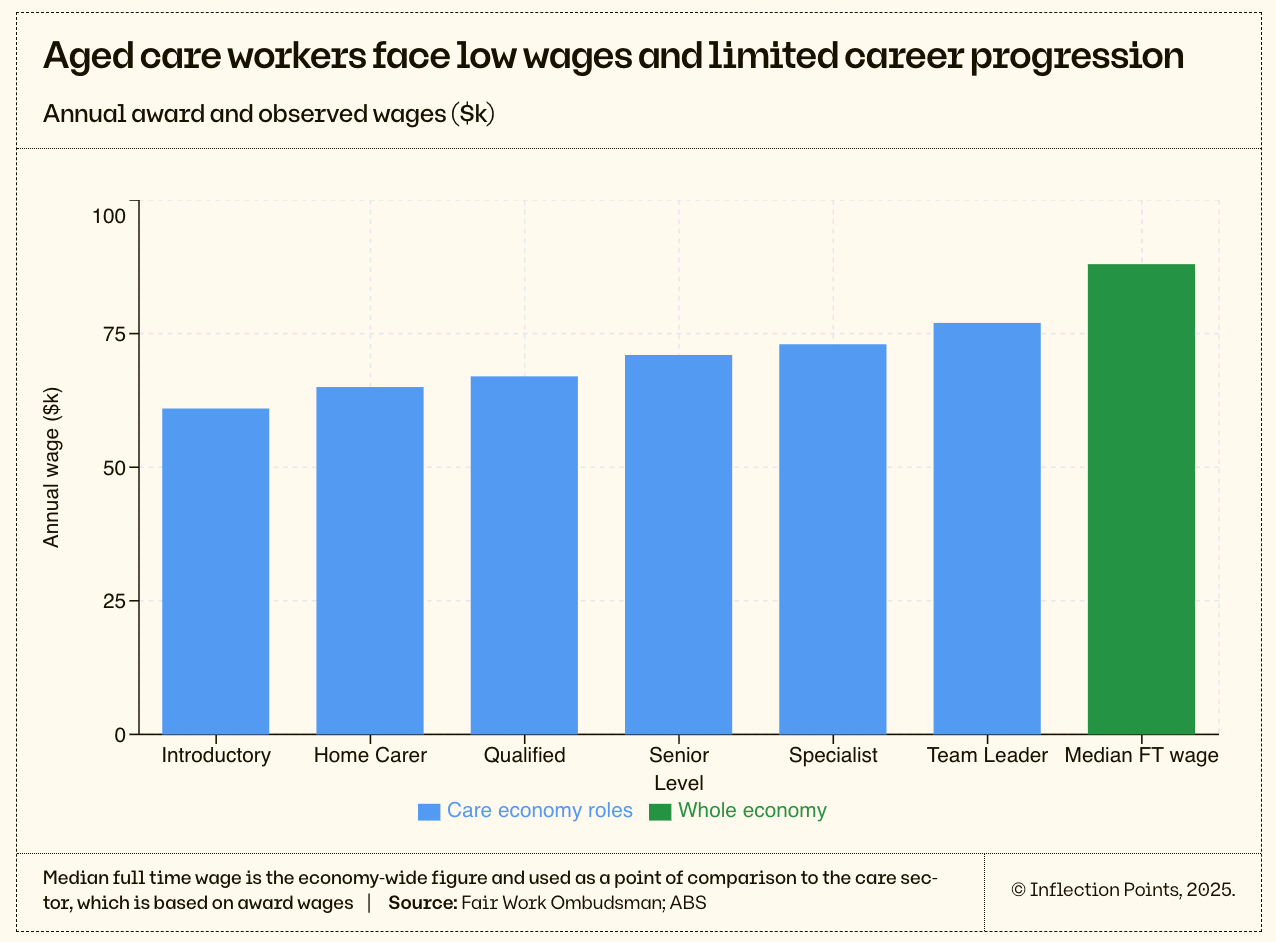

There are three main problems driving the workforce shortage. The first is low wages, the second is lack of career progression, and the last is poor conditions at work.

But before diving into those, it’s worth recapping how the home care market works.

In simple terms, demand is driven by demographics, and supply is driven by government regulation, funding, and award structures. That is, the government says “we will fund X packages and they will be worth $Y”. The middlemen—providers—are then allowed to charge a maximum of $Z for the administration of care and packages. These providers can use a third-party employer of personal care workers, or they can directly employ those workers themselves. All workers are paid at a mandated award rate based on their role.

The government then disburses taxpayer dollars to clear this constructed market.

That’s a bit of a simplification of the value chain in the home care economy, but ultimately it shows that the government largely shapes the rigid economics of this market by controlling and capping demand, and also by setting the prices of the various services involved.

Home care workers have relatively low wages

Low wages are a major driver of the care economy labour shortage, given pay is below similarly skilled occupations, no doubt partially due to the impact of gender biases that undervalue highly feminised industries. Without outside market forces shaping the sector, wages historically grew slowly and off a low base.

To their credit, the Australian Government increased the minimum wage for at-home aged care workers by ~36% over the last 4 years. These are once-in-a-generation pay increases funded by the federal government that have raised the award wage for a full-time employed home care worker in aged care from $45,000 in 2022 to $61,000 in 2025. It’s still far less than the median full-time wage ($88,400), but it’s certainly a big change, and more than the median full time annual salary for the equivalent role in the US ($34,000 USD, or ~$52,000 AUD). This wage increase alone might mean that the staffing gap closes substantially, but we’ll have to wait until the next Workforce Survey to see.

Government-funded wage rises are unlikely to fully close workforce shortages. Highly productive sectors are producing more for less every year: think manufacturing. Meanwhile, care work becomes less and less attractive over time: few perks at work, and relatively lower and lower wages compared to jobs taking off in the other parts of the economy. While taxpayer-funded wage rises are inevitable, governments will likely move slowly on them, and they will always be chasing the increasing salaries of more productive sectors.

Home care roles offer limited career progression

Career progression matters because having experienced, specialised carers matters. Even if good starting wages can attract lots of people to do entry level care roles, we’re not just looking for bodies in homes. A strong care economy should have skilled, experienced carers: people who are specialists in adults with particular mobility issues or dementia, for example.

The industry experiences a lot of turnover: in 2021-2022, it was 41%. Some of that turnover is a care worker moving from one employer to another—but some of it is people dropping out of the industry altogether. Once again, we don’t have good data to work out what proportion that is.

It is exceptionally hard to see real career progression as a home care worker. There are 6 levels to the category in the Social, Community, Home Care and Disability Services (SCHADS) award, capping out at $77,000 with a Cert IV and supervisory role—only 26% above someone with no experience at all, and still below the median wage. This is obviously discouraging to experienced care workers, and not a strong case for people considering whether to stay or leave the industry.

The current award wage progression is structured such that you need a new certification or a certain number of years of experience to get to the next pay grade (for example, 4 years to move from Level 3 to 4). The Australian government clearly cares about home care workers being skilled, having made many relevant TAFE courses fee-free (or heavily subsidised) for eligible students.

Certifications and years of experience are the best proxy we currently have for understanding how skilled a worker is, but we can get better at measuring this. For instance, there are lots of reasons people don’t go to TAFE—they might be caring in their job and also at home, or they might have a lot of difficulty with English or academic environments, or they might not be eligible for fee-free TAFE. So some workers, who have put in years of hard work in the home care sector, may not be able to move up the award scale, and struggle to transition to different careers that might build off their skills. That’s even the case for those who have spent hundreds of hours with patients and developed soft skills, familiarity with certain conditions, and administrative and management prowess.

This means we might be losing really skilled workers because they can’t progress fast enough, even though they’re absolutely smashing it in the job.

Offering better career trajectories could also transform the types of workers attracted to the industry in the first place. It could fundamentally transform people’s view of a job as “just for now” or “just to pay the bills” into a long-term commitment. And we’d all rather someone who viewed this as their career, rather than a side-job, to be caring for our parents.

And finally, on a more personal note, career progression is important because it gives hope, meaning and structure to workers. Many people reading this piece likely work in an office job. Many of us have the next title and pay rise in mind, or have climbed a ladder to get to where we are. That’s satisfying, and gives us something to look forward to. Why shouldn’t home care workers have the same? It’s an industry in which workers develop meaningful skills over time, skills that could be translated to nursing or care administration with little stretch of the imagination. But our current system hasn’t set workers up to get there with any ease.

Working conditions are unpredictable, and often poor

The flipside of entrusting your loved ones with home care workers in vulnerable situations is that these workers have to enter new, private environments all the time. This is the third problem: working conditions. It’s not clear what they’ll be like—is the client a hoarder and their house physically unsafe, will the family ask for more work than the worker is paid to do, will it be an emotionally hostile situation? Aged care workers have to do work that you don’t even want to do for your parents, some of it filthy, and much of it just physically hard. Given these conditions, it’s hardly surprising that fewer people than we need want to work in the sector.

Home care workers experience injury rates of 12-20% a year by various global estimates; in Australia, a 2019 sample of 5,000 home care workers found 45% had experienced a workplace injury in their careers. Safework NSW lists risks to home care work as muscular stress, slips, trips and falls, workplace violence and aggression, and psychosocial hazards (where such hazards like ‘role overload’ and ‘low job control’ cause stress responses). Atticus Maddox and Lynette Mackenzie published a study in 2025 which found that 76% of occupational therapists they sampled had experienced workplace violence (verbal, physical or sexual). Occupational therapists are not the same as home care workers, but they represent a similar cohort of professionals entering into a vulnerable person’s home to provide them a service; it’s likely that a study on home care workers would find violence rates to be similar.

Technology will disrupt the care sector

With such a bleak outlook, one could feel despair. But with new technology on the horizon, like rapidly innovating AI use-cases, there’s cause for both optimism and caution. Used well, these have the potential to follow in the footsteps of historical technological improvements to patient care. But early signs suggest that some technologies in the workplace, like monitoring software, can be hostile to workers’ experiences, threatening both its uptake and possibly worsening already poor work conditions.

Improvements in care are possible

AI and other new technologies offer workers two compatible opportunities:

To spend less time doing undesirable tasks. For instance, by using machines to perform tasks that have previously required humans, particularly those tasks that are high-cost or time-consuming.

To improve patient care. For instance, by using technology to better triage and manage patients, improving their experience and making sure workers are focused on doing the highest value tasks.

For example, take innovation in patient beds as an example of doing fewer bad tasks. Previously, nurses would spend time each day cranking their clients’ beds to be in comfortable positions. Not only did this pull nurses away from important things they could be doing, but it also meant patients relied on support workers for a very basic part of their day. The question that was asked in the 1960s, as part of a detailed study in the UK, was:

What mechanical and powered assistance would be necessary if the same quantity of care and attention had to be given with half the present quantity of woman-hours

In addition to reducing the burden on labour in the system, the development of hydraulic and then electric beds allowed for greater independence among a cohort typically facing a loss of such agency in out-of-home care.

Another example is the remote monitoring of client vitals. Historically, care workers were required to check vital signs by physically visiting patients and checking if they needed support. Today, care workers are able to check in more regularly on their patients through remote systems, including many which provide alerts when things go wrong. This has reduced disruptions for residents, enabled staff to deliver a similar level of care to a greater number of patients with continuous, rather than periodic, monitoring.

Both of these innovations show that improvements in care can be enabled by technology. Not only can this technology deliver more efficiency gains, but it also often comes with an increased quality of care and sense of independence from the residents or patients.

But these are physical changes to home care. AI and software platforms present an interesting new nexus that asks whether more or better information, organised differently, can change home care.

We’ve seen genuine innovations

There’s reason to believe that these new technologies will deliver similar improvements of care, across each of the categories outlined above. While it’s too early to know what fraction of activities done by humans will either be eliminated or done more efficiently, it’s clear that new technology will play a role in addressing challenging labour shortages.

Spending less time doing undesirable tasks

There have already been innovations that have pushed workers to be able to focus on more critical tasks, by automating or speeding up routine or low-value activities. Consider three areas.

AI tools reduce administrative burden, as they have across the economy. Innovations that have helped other parts of the economy have also spilled into the aged care sector. Hireup is an Australian based disability and aged care support company with 11,000 NDIS and aged care clients and 14,000 workers. Jordan O’Reilly, the cofounder of the company, told me that they’ve started implementing AI to summarise customer care calls, saving at least 10 minutes of administrative time after every call. This is one of the simplest applications of generative AI: supporting customer service staff. Stanford and MIT academics produced the first paper that studied generative AI’s economic impact when deployed at scale in a business: that business was a customer service centre. They find that generative AI chatbots can increase the number of issues centre agents can resolve for customers by 14%, and that most of this gain accrues through less experienced and lower performing staff.

Smart scheduling leaves more time for patients. Biarri, an Australian commercial mathematics firm, helped Australian Unity with a new algorithm to optimise worker schedules (i.e., route optimisation). They had enormous success—15% reduction in cost per visit, 15% reduction in travel time, increase in visits delivered as planned from 60% to 90%. That’s an awesome outcome for workers, who don’t have to spend as much time in traffic or going forwards and backwards, and for patients, who see their care provider when they said they were going to be there.

Robots can reduce physical labour if we can get them right. One promising area is the use of advanced robotics to support elderly patients receiving care—robotics is particularly important because AI on a computer alone cannot lift an old person (yet). Perhaps unsurprisingly given its aging population, Japan has been at the forefront of developing such technologies. Waseda University, in collaboration with industry partners like Hitachi, have developed the AI-Driven Robot for Embrace and Care (AIREC). A similar technology is in development by MIT. They both aim to assist elderly residents to do day-to-day tasks including:

Getting in and out of bed

Putting on clothing and socks

Getting in and out of a shower

Sitting on a toilet

Collecting basic biometrics data (e.g., blood pressure)

These impressive robots are slated for commercial release in 2030, and will initially cost $67,000. They will likely be most viable in residential care facilities, where they will help with the tasks they do best, enabling the stretched care workforce deployed to other key tasks.

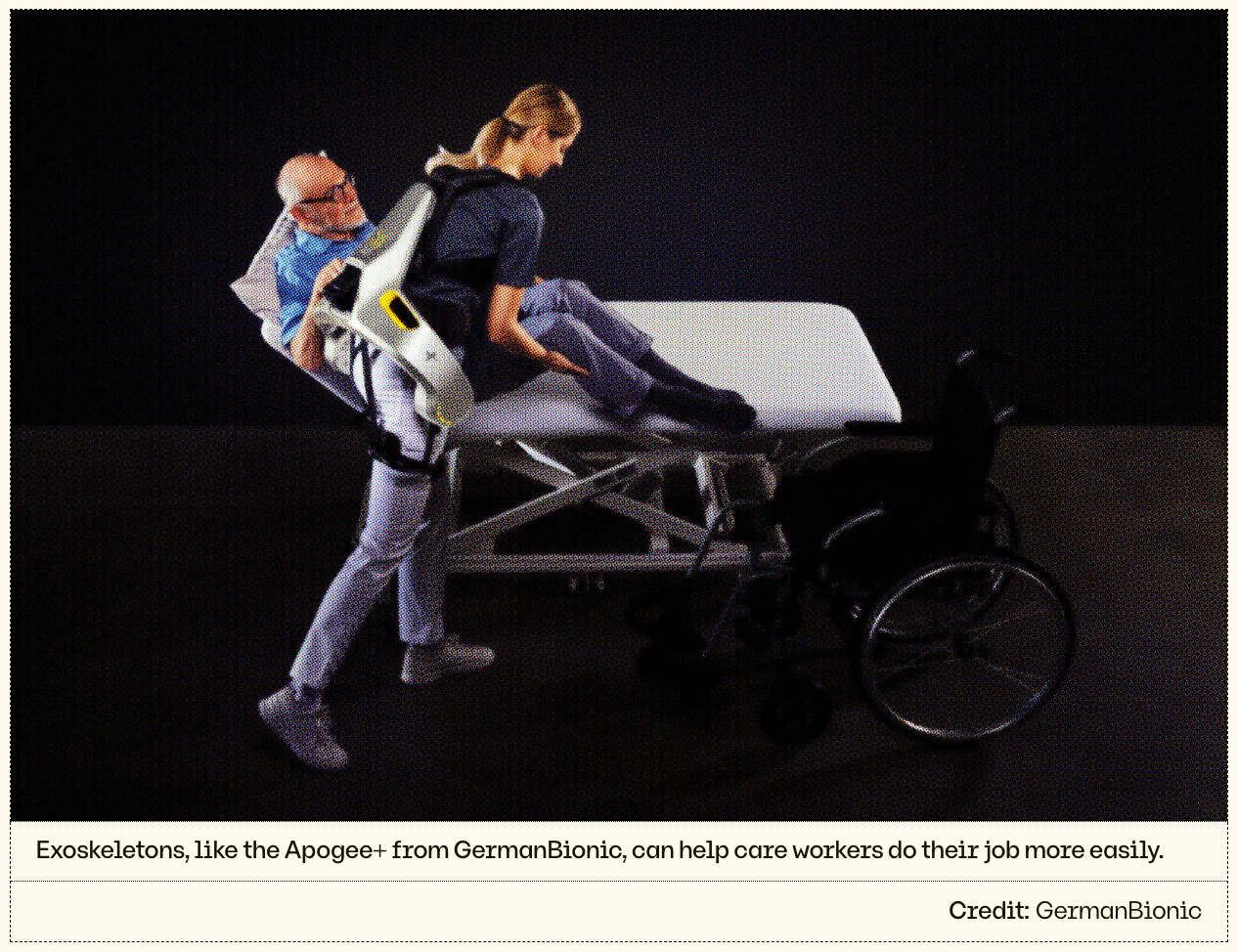

Less complex assistive technologies are already deployed in nursing homes. For example, lifting patients has been made substantially easier with wearable exoskeletons for workers. These devices sense the action that the worker is trying to undertake and activate mechanical features (e.g., extra resistance in some parts, motors and hydraulics in others) to reduce the strain on the worker lifting. Robot adoption in Japanese nursing homes has been linked to improved quality and productivity of care, and has increased employment and retention.

Additionally, less complex labour intensive elements outside of care provision have seen progress. Time consuming tasks—like cleaning floors and transporting linen—have all benefited from the adoption of industrial scale robots. AI has been important in enabling this, given the importance of situational awareness in aged care facilities (as aged care facilities are populated by elderly residents); large neural networks have played a crucial role in ensuring robots do not disrupt or injure residents.

It’s critical to note that many of these robotic developments are targeted at residential facilities, rather than home environments. That’s because homes are often non-standard, have a higher degree of clutter, and large, expensive pieces of equipment are harder to justify for one older person compared to dozens of them in a residential facility.

But improving efficiency in standardised environments, like residential facilities, is still valuable. It frees up workers to navigate the more complex and high-value tasks that make the best use of their skills; it might even relieve some demand for residential care workers, allowing more carers to work in home care. And, eventually, some of this technology will adapt to non-standardised environments like home care.

Improving patient care

We‘ve also already seen substantial improvements in patient care using technology, allowing for patient care to improve in a cost-effective way through smart investments.

Machine learning predicts health risks, and enables triage. Cera is a UK based digital-first home care provider. At each of the 2.5 million patient home visits they deliver each month, Cera’s carers and nurses log patient symptoms and observations in the Cera app. AI algorithms then use this data to predict a patient’s risk of falling or developing an infection. This allows Cera to flag high risk patients and mobilise staff to prevent these outcomes. Cera has experienced enormous success at using AI to predict whether clients will have a fall—calculating a client’s risk of falling with 83% accuracy, 7 days in advance. This technology has been endorsed by the NHS, and is already used in almost two thirds of care systems across the NHS. By predicting when clients are at risk of falls and providing them with additional support, Cera can both improve the quality of their service users’ lives, and prevent the extensive costs of call-outs for staff. Speaking on the topic, Charlotte Donald, Cera Care’s director of operations, said:

Most families who have an elderly relative will have experienced the impact or fear them falling. Falls are painful, some people never fully recover from a fall and those who do tend to lose some confidence in themselves and their independence. Preventing one person from falling is significant, being able to prevent tens of thousands is nothing short of groundbreaking.

Having access to this technology makes it easier to systematically understand what kind of care and preventative support is needed for different service users, and is seen as a win-win-win across clients, workers and payers.

Chatbots can increase the average skill of workers, but risk atrophying the skills of experienced carers. ChatGPT itself is promising, though not perfect, in helping home care workers work out what to do on the job. One study of popular large language models (LLMs) to see how close they got to gold standard responses in 10 common home care scenarios.

They concluded that “although not yet surpassing professional instruction quality, these models offer a flexible and accessible alternative that could enhance home safety and care quality”. Given home care can be done by people with no qualifications, having a chatbot on side might improve the average skill of workers. But there is a risk of skills atrophy, as one study in the Lancet found occurred to endoscopists before and after having access to AI to diagnose adenomas. This might make highly skilled workers less skilled over time as they come to depend on AI.

Critically, and unlike a specialist, a home care worker faces a very wide range of daily tasks, which spans multiple patients, overlapping conditions, different environments, and any number of tasks. In this way, access to a well-calibrated chatbot or similar may offer a lot of value in helping with tasks a worker has never encountered before, and may well never encounter again.

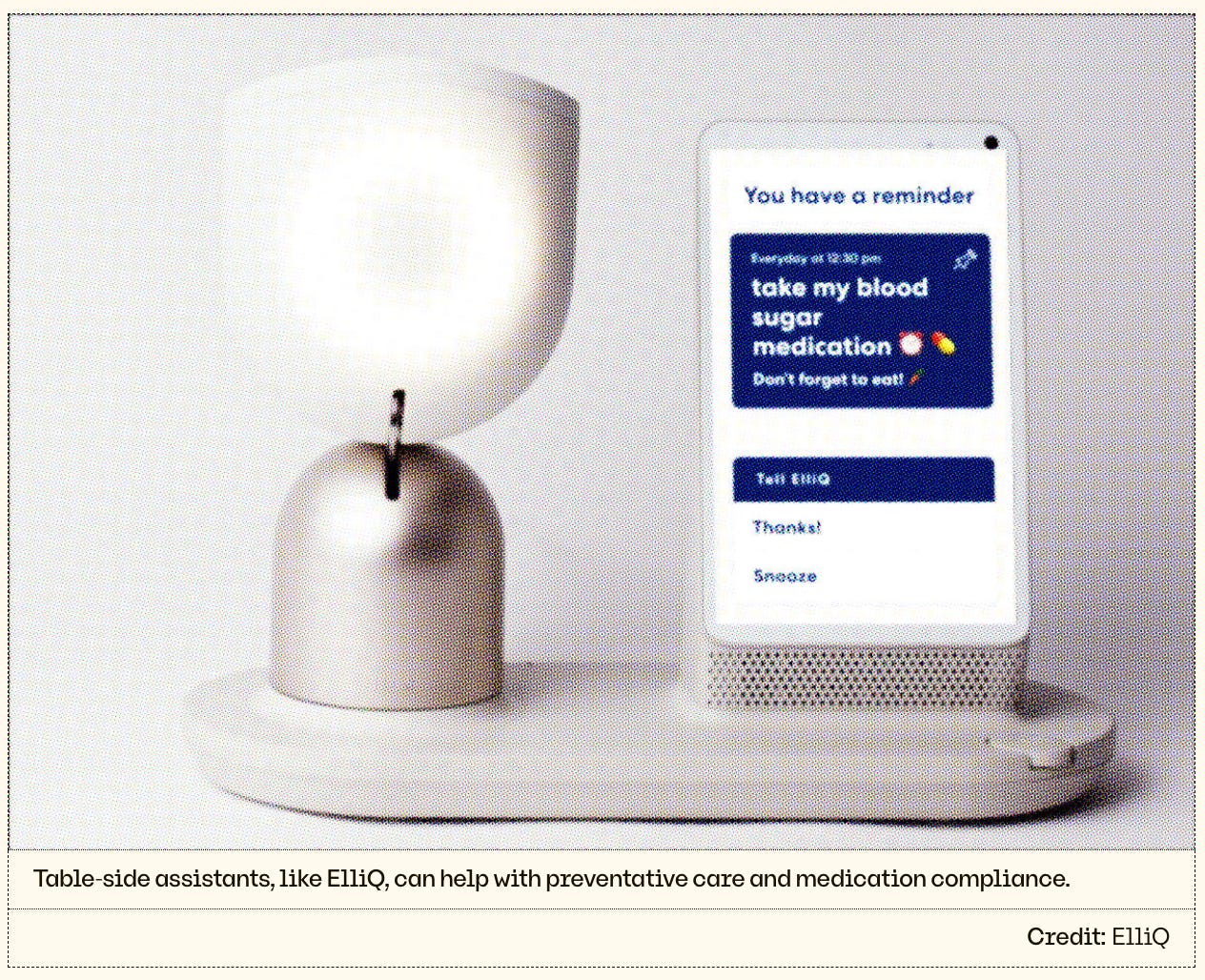

Digital companions could combat loneliness in older people. Critically, as baby boomers who spent their working years navigating computers, the internet, and smartphones begin to move into aged-care settings, their digital fluencies and expectations of care will begin to reshape what is possible. On-demand services may become more sophisticated, as our aging population becomes more familiar with app-based interfaces. This may give rise to the development of companion-based technologies—varying from table-side assistants to humanoid robots (including one developed in Australia). Early studies from Japan on PARO, a therapeutic AI inside a stuffed toy seal, have found it improves medication compliance, anxiety, agitation and depression in adults with dementia.

To some, this sounds dystopian. How can older people get a sense of connection from a robot? Wouldn’t we rather they get it from a person? In an ideal world, technology will give home care workers more time to spend with their elderly clients in a purely social manner. But if studies continue to show improved health in older people who are using these digital companions, there’s no reason not to invest in them too.

But innovations are costing workers

On another hand, the expansion of new technology tools runs the risk of eroding workers’ rights. In a sector which already struggles with worker retention due to poor work conditions, limited career progression and low wages, we should be concerned about the risk that this poses.

In the care sector, bosses are already using AI and associated technologies in a way that harms workers. Workers have every minute clocked by GPS, and these inputs are fed into AI systems that rank and assess them. Workers express that this is driving extra work: having to argue with their bosses about the GPS tracking messing up their paychecks. They’d be right to worry about what the AI ‘thinks’ about these inputs. Some workers complain that their shifts are changed inexplicably—that they’ll call a client to confirm that they’re coming, only to click into their apps and find they’ve been switched to a different client at the last minute. Maybe it’s AI, maybe it’s a simpler if-this-then-that machine, but regardless of the underlying technology, it has workers worried.

There are worries that they will be asked to use new apps and tools that tell them what to do and they feel pressure to act, even if their judgement says “we don’t need to do that”. The UTS Human Technology Institute did a deep dive with nurses, and their experience is illustrative of how new assistive technology in care settings can actually make work harder. Consider one nurse’s story:

We were using facial recognition in NICU to confirm babies’ identities before administering medication and the system kept giving false alerts ‘face doesn’t match’. So you constantly have to override and say ‘yes, this is the right baby’. It causes extra work and also defeats the purpose if you [sic] just going to ignore all alerts.

It isn’t that AI is bad in and of itself, but many current use cases put employers on the front foot, chasing slightly better margins, and think little of employees. This typifies the care sector’s core problem: it’s structurally limited in its embrace and investment of new technologies.

The sector isn’t geared to adopt new technologies

Given the promise of AI, one would expect aged care operators to be rushing out to roll-out such tools. Unfortunately, substantial barriers exist in technology adoption in the sector. This isn’t just speculation: currently less than 10% of aged care providers have used the My Health Record platform, which is used by 100% of Australia’s GPs. These barriers will flow through to the adoption of AI by care economy participants. Consider three unique factors of the sector which have prevented its adoption.

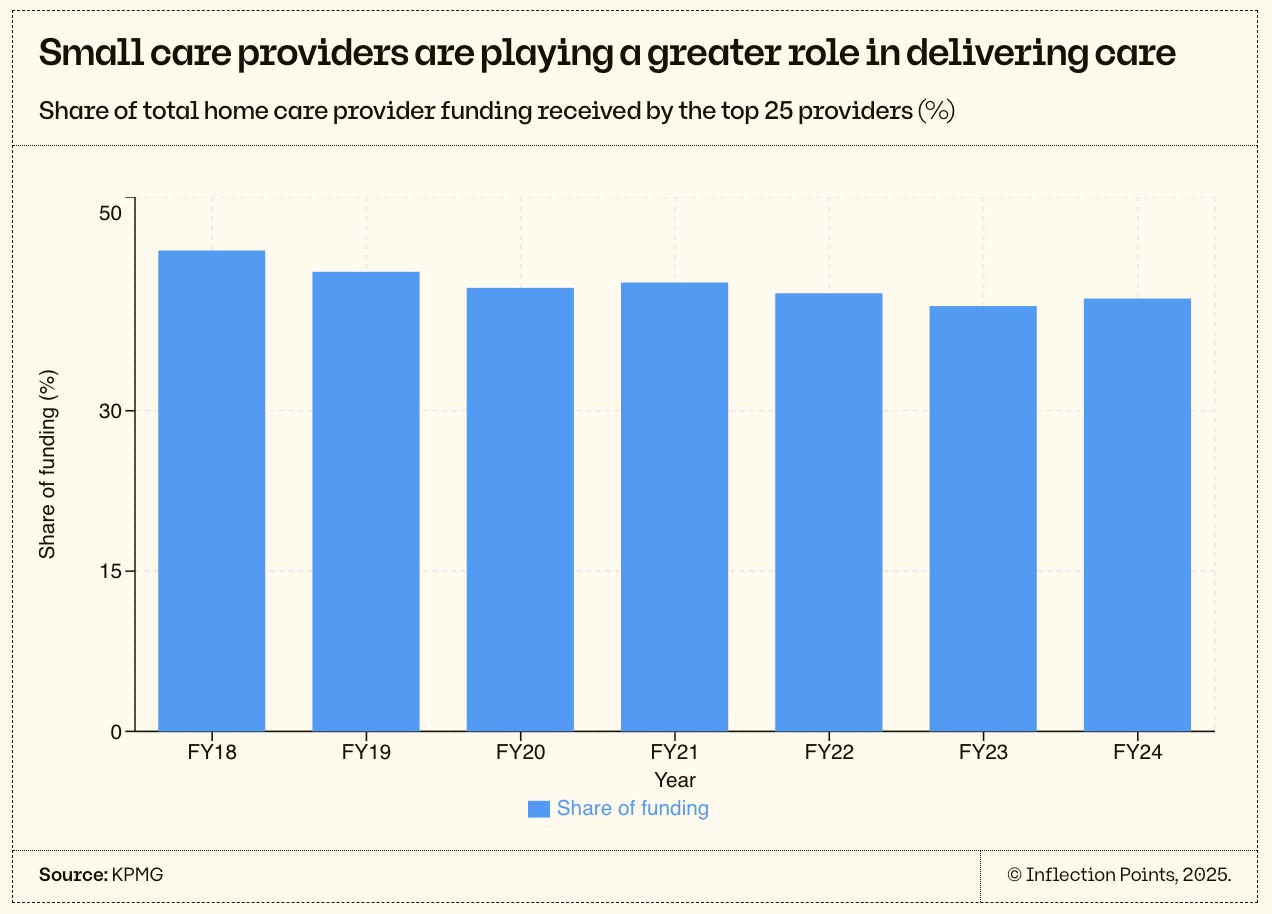

The sector is fragmented

Australia’s aged care system is notoriously fragmented. There are more than 850 approved providers of home care services and more than 600 approved providers of residential care operating across the country, the vast majority of which are small not-for-profits. In home care, more than 95% of providers (representing nearly 60% of the sector’s activity) each receive less than $70m in government funding. Across the industry, the average government funding per home care provider is $10m.

This fragmentation undermines investment in new technologies: most small providers are unable to take advantage of the economies of scale or pools of capital required to invest in the platforms and equipment which underscore productivity growth. In the case of AI, smaller providers may also struggle to grapple with the ethical demands of deploying AI across a highly vulnerable population. And with many operators siloed into specific geographies, knowledge transfer across the sector is difficult.

It remains to be seen whether the involvement of private equity (PE) in home care (such as Quadrant’s 50% acquisition of St Ives in 2016) leads to investments in technology to deliver quality care at a lower cost. Quite reasonably, many Australians are worried that it will instead lead to the erosion of quality observed in the United States as PE firms have purchased residential aged care assets. Because PE firms are looking to make a substantial profit in 3-7 years, they are incentivised to find shorter-term profitability, rather than the profitability that may be yielded from long-term investments in innovative technology and capacity. These incentives can lead to bad outcomes: one study found that PE ownership of US nursing homes led to an increase in resident mortality of 11%, alongside lower rates of compliance with care standards. With this in mind, we should be wary of expecting sector consolidation alone to drive meaningful improvements in care quality in home care.

Regulation & funding models discourage investment

The prevailing design of the home care economy leaves providers with little cash to invest. Tight controls on cost and provision are understandable—after all, the Aged Care Royal Commission revealed many dodgy practices, such as charging clients ‘exit fees’ of more than $4,000 to disincentivise changing providers. But this doesn’t mean the government has got its payment structures exactly right. For instance, 32% of home care providers weren’t profitable in 2022-23, meaning there was either no cash to reinvest in innovation, or the investments they were making left them unprofitable. Providers, profitable or unprofitable, also aren’t paid based on the quality of client outcomes—they’re paid based on the size and number of packages that they have on their books. This means incentives to invest in marginal improvements are low.

On top of this highly regulated funding model, care economy providers must navigate clinical guidelines associated with how care is delivered. While these quality standards are essential to preventing the widespread failures observed throughout the Royal Commission into Aged Care, their continued evolution risks adding undue complexity to delivering services in a digitally enabled manner.

Ben Maruthappu, the founder and CEO of Cera, attributes the success of his 9-year-old company (already one of the largest home care providers in the UK) to innovating in all parts of the business, based on the needs of frontline staff. That means his technology development has focused on both the flashy, important bits (the fall prediction capability described earlier) and the more boring, but equally important bits, like digitising paperwork and auto-filling forms. He says: “We have carers that apply for work because of the tech—because they hear they can get scheduled for work more easily and deliver more care”.

Ben’s company has flourished against all odds. He tells me that one of his biggest barriers to innovating further is the current funding framework for home care providers in the UK: providers are rewarded based on the volume of care they provide, rather than being incentivised to embrace prevention or focus on outcomes. He wonders how things might be different if providers were paid based on outcomes, rather than hours: avoided hospitalisations, for example.

Ben’s got a good point. The costs of hospitalisations and residential aged care far exceed the cost of home care, and so if home care is particularly good and keeps older people out of institutions, then it’s a cost-effective investment. A different payment structure could be used to explicitly incentivise home care providers to deliver high quality care, and reduce overheads associated with an ageing population.

Cera’s payment-incentives challenge resonates in Australia too. Australian home care providers are explicitly only allowed to charge their actual costs, including a margin on the cost of capital, to deliver services that are reimbursed by the Australian government. In 2026, these prices will be explicitly capped. This ‘cost-based’ pricing makes sense to prevent the rorting of Australian taxpayer dollars. But it poses a huge barrier to productivity-enhancing investment.

Recommendations

To support the adoption of these platforms across the economy, the government should consider driving three substantial shifts in the sector.

Change incentives to drive innovation

Use microcredentials for progression

Develop worker incentives

Reform incentives to drive innovation

As has been established, most Australian home care businesses have limited margin to reinvest in delivering better outcomes or more efficient service. And they’re not necessarily incentivised to. If it takes half the time to care for a client, then they’ll have their revenue cut in half too. Under these conditions, it will take a long time for providers to catch up to best practice.

If we want innovation, the Australian government has to radically restructure the incentives of home care companies to invest in cutting-edge administrative and care-provision technology and processes. That would likely involve reshaping hours-based funding models, towards a measure that takes into account the outputs (quality of care) rather than the inputs (number of workers).

That could look like a base payment model to providers, per the current model. Then, an additional dividend, based on quality outcomes (avoided hospitalisations, for example, against an expected base). This model would allow successful, innovative providers to make capital investments and scale, and give all providers greater reason to try.

Use microcredentials for progression

Victor Dominello’s call for a skills wallet makes sense across the economy. I want to push the idea even further to say that care workers should be able to upskill, move up pay levels and ultimately move into adjacent fields through their work alone. In critical industries like home care where we have worker shortages, the government should actively redesign credentialing processes and award systems to automatically recognise capabilities and skills learned on the job.

Think of it from a client perspective: if you could have a worker in your home who is certified based on what they actually did on the job (demonstrating skills, following protocols, and creating good outcomes) versus through some number of years or TAFE certification, which would you prefer?

The government could develop a digital microcredentialing tool while simultaneously reforming its award system and accreditation requirements to make those microcredentials valid. This would require a lot of testing to make sure it is as watertight as it can be in certifying workers, but it’s likely to be the assessment model of the future.

Picture this: a smart schedule assigns workers to clients based on existing and progressive skills they’re gaining, and clocks the hours spent. The notes workers take record their actions and patient outcomes. This data, likely processed in part by AI, is then used to assess competency, and the model can automatically assign credentials (e.g. 200 hours of dementia care that meets care guide expectations). These credentials can then be recognised as part of earning a more advanced degree like nursing.

This would enable home care to be an industry with real progression, and a stepping stone towards other related careers if desired. Plus, in a demanding job, it would be incredibly motivating to know that the next micro-promotion is just around the corner, rather than four years away or available only through extra work and sitting exams out-of-hours. For this whole system to work, the government’s key contributions would be:

Developing a mechanism to pull anonymised data from home care businesses’ client notes and schedules

Developing a certification algorithm to analyse this data

Running a pilot demonstrating that the certification algorithm is accurately classifying people’s skills and is at least as good as, if not better than, in-person testing

Coordinating various government departments to support and recognise these new certifications, including Department of Health and Aged Care, Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, the Australian Industry and Skills Commission

Making an application to the Fair Work Commission to overhaul the award system to create more granular levels based on these new certifications

Cera currently has its own internal pay progression known as ‘Career Pathways’. They provide learning and development pathways from sector newcomer to leadership, including nursing qualifications. Cera has used AI to scale this training across its workforce, delivering 1 million hours of training to date. 45% of salaried operational vacancies were filled internally due to this training pathway. They’re proof that not only can home care be a meaningful career path, but that setting it up as such is critical to running an effective, fast-growing home care provider, and that AI has an important role to play.

It would be nice if every home care provider currently operating was like Cera, but these systems only currently work at substantial cost to the employer, and are infeasible for smaller operators. Cera also still ultimately needs their staff to undergo face-to-face certification due to government requirements.

The government needs to rethink the incentives of this labour market that it designed to be more reflective of the skills and desires of its workforce. The reality is that the government has full control over how people can be certified, and how much they should get paid once they are. If we are serious about managing the oncoming aging population crisis, making home care a substantial career is a critical unlock for our future.

Develop worker incentives

If reforming business incentives is one side of the coin, reshaping worker incentives is the other. Home care is uniquely reliant on its workforce, but workers often see little upside from taking on extra shifts, adopting new technology, or helping their employers solve structural challenges (two-thirds of aged care services employ personal care workers on awards). In fact, the system too often disincentivises flexibility and innovation at the frontline. Yet with well-designed incentives, governments and providers could unlock a win-win: higher productivity for employers and better pay and career satisfaction for workers. Consider three mechanisms that could be implemented.

Incentive bonuses: there are many win-wins available to workers and their employers. A last-minute shift, referring a friend, filling out documentation on time are all incredibly valuable to an employer, and can be made more valuable to an employee. Where an employer might be calling around to scrounge up an employee for a shift, algorithmic tools can automatically calculate the value of that shift to the employer (considering for example the cost of losing the client and the likelihood of that happening). They can then offer a portion of that value to the employee on top of their regular rate.

Series A startup Jolly is emerging as a key player in the US home care incentives market, already deployed to more than 30,000 frontline workers. Its gamified app lets employers set priorities and allocate funding, which is then delivered to staff as targeted incentives. The approach has driven measurable improvements—for example, Jolly campaigns lifted on-time documentation completion rates 30%, boosting providers’ ability to get paid promptly. For workers, these campaigns have translated into a modest but meaningful lift in overall compensation.

Tech dividend: employers have a particular difficulty getting staff to embrace technological and ways of working change. Australia has been particularly slow at adopting AI, and the healthcare industry even slower—the cumulative impact being that home care is very tech backwards. If employers offered a portion of the cost savings or revenue improvement offered by a tech change to employees that actively participate in making it happen, both could win. And there’s no downside to the employer.

On top of the redesign of incentives and payment structures suggested above, the government also has a role in this to provide international best practice to the highly fragmented market of home care agencies. Many have worried about how to pay their staff more and struggled to find the time to develop new mechanisms. As part of the government’s broader innovation push, information is a critical tool.

Now is the time to make the care economy work

My mum was an extraordinary carer for my grandmother. I hate to publicly admit it, but I’m scared that I won’t be nearly as good as she was. But I love my parents dearly, and I need to know that they’ll be in good hands.

If we want that for our families, we need to start by treating care workers better. That means removing the barriers to technologies that can make their jobs easier and make the lives of those in their care more fulfilling.

New technologies can help employers put a price on an employee going above and beyond, and provide them a financial incentive to do so. They offer us better data on worker actions, skills and outcomes; this data changes the bar at which we can give someone a promotion. And, they might make work a little easier and less dangerous, as exoskeletons and robots in the works come onto the market.

AI, robotics and other technologies have the potential to improve the care sector. The real question is whether they will be adopted and if that adoption will leave residents and workers better off. That’s something government can, and should, make happen.

Good to see your notes of optimism...